How did eugenics develop and why did it persist into the late 20th Century

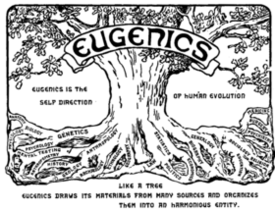

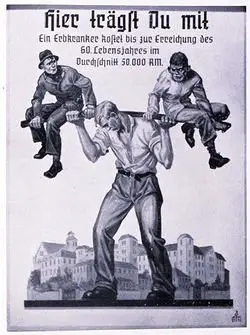

Eugenics. It’s a term we often associate with Nazism and Hitler’s nonsensical ideologies behind his ambition to create the “Aryan race”. But, do we know exactly what this term means, or are we quick to dissociate with it due to its implications? According to Google, eugenics is defined as “the science of improving the human population by controlled breeding to increase the occurrence of desirable heritable characteristics”.[1] Basically, the philosophy of eugenics was such that humans were either “fit” or “unfit” to reproduce – those with physical deformities, mental shortcomings, and skin colors other than white all fell into the “unfit” category. Those who were tall and strong, intelligent, and most importantly, white, were considered “fit”. Eugenics is a “science” predicated upon racism, classicism, and sexism – so why in the world would we want to study it?

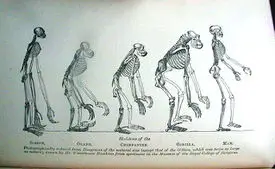

The answer is that studying such “failed” sciences of the past can give us incredible insight into the origins of scientific theories we now hold to be true. Darwin’s own theory of natural selection was rife with racist and misogynistic undertones, but despite this, it is still the accepted science of the day. Scientific theories aren’t an “all or nothing” deal. Some parts may hold weight, while others fall off as time goes by and new scientific discoveries are made. Darwin, long before the discovery of DNA, thought genetic traits were inherited through “gemmules” in the blood – he even went so far as to perform blood transfusions on rabbits to prove his point.[2] He called this theory “pangenesis”. Ever heard of it? Probably not, as it was dead wrong!

As modern students of history, we must divorce scientific theories of the past from the unavoidable societal underpinnings of their time; it is imperative that we not place our own 21st-century judgment upon centuries old studies. It is extremely difficult to do science in a vacuum – biases inform even the most seemingly objective scientific endeavors, even today.

Where did eugenics come from?

The philosophy of “breeding to better the human race” is an old one – an ancient one, actually. In 380 BCE, the well-known Greek philosopher Plato published his seminal work, the Republic. This book contains the first written direct reference to the selective mating of the human race that exists in the historiography of eugenics. In Book V, Plato says to Glaucon, his older brother: “Do you not take the greatest care in the breeding? …there is no reason to suppose that less care is required in the marriage of human beings.” Plato then goes on to say: “The good must be paired with the good, and the bad with the bad, and the offspring of the one must be reared, and of the other destroyed; in this way the flock will be preserved in prime condition.”[3]

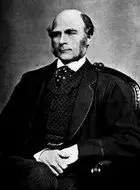

Another eugenics pioneer, who came a couple thousand years after Plato, was Francis Galton, a member of the British landed gentry and half-cousin to Charles Darwin. Charles was Francis’s older cousin and role model – they had been corresponding since Galton published his Narrative of an Explorer in Tropical South Africa around 1853.

Six years later, after years of writing letters back and forth, Darwin published his definitive work on evolution, On the Origin of Species, in 1859 – this was the book that would forever change Galton’s life. The chapters on animal breeding, especially Darwin’s first chapter, “Variation under Domestication”, fascinated Galton.[4] In the preface to his first book on the subject, he admits that he sought to study heredity for purely “ethnological” reasons, so as to investigate the “mental peculiarities of different races”.[5]

Francis Galton was primarily interested in the maxim we now call “nature versus nurture”, and set off on a years-long study on whether or not human ability was simply hereditary (passed down through generations) or could be taught. His primary research interests were the pedigrees of the “great European families”, as well as his own family’s lineage. Galton published his findings in a book entitled Hereditary Genius in 1869. The results of his many studies led him to believe that: “Human mental abilities and personality traits, no less than the plant and animal traits described by Darwin, were essentially inherited”. Galton tossed aside the notion that higher learning could be taught, instead insisting that humans were simply born exceptional or born unexceptional, and nothing during their upbringing could change that notion. He thus became known as the “father of behavioral genetics”.[6]

Positive eugenics vs. negative eugenics

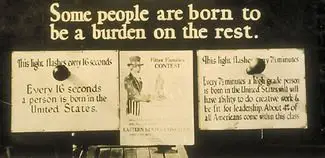

Plato’s Republic advocated a program of selective mating to produce an exceptional class of humans. This meant that the most intellectual and beautiful people among any given society should see it as their moral duty to reproduce and create similar outstanding specimens, and so on, and so forth. Francis Galton took this idea a bit further, advocating for positive eugenics as a method of breeding that used incentives like education, tax benefits, and stipends for members of the upper echelons of society who reproduced. Put simply, positive eugenics held that people of lower/inferior classes should selflessly forgo having children, while those of the higher orders should reproduce as often as possible in order to benefit their nation.

Plato did not advocate for the sterilization of the “lesser” specimens of humanity – sterilization often consisted of castrating and spaying of the mentally unfit and racially impure. This was known as negative eugenics, and it was an entirely different subset of eugenics born of insecurities among nation-states that formed centuries long after Plato’s time. During the early twentieth century, birth rates among white Protestant individuals were declining in Europe, while birth rates among the Irish and lower classes were rising exponentially. This data was published in a significant number of high-brow weeklies and journals, and such findings inspired a general fear among the upper classes of all European, British, and American societies that they would soon be overtaken by swarms of “inferior” citizens – it was simply a matter of time and numbers.

These insecurities led to a form of eugenics that had even darker implications. In its most extreme form, negative eugenics called for the use of euthanasia to prevent the “unfit” from overpopulating the world with “weak” individuals – this could apply to those who were physically disabled, mentally “unfit”, or simply poor and destitute. Another “lesser” form of negative eugenics sought to sterilize these classes of people rater than systematically destroy them. This type of eugenics also banned marriages between people of different races in order to prevent racial miscegenation. William Goodell, an American gynecologist, is thought to be the first promoter of negative eugenics – this ideology first surfaced during the late nineteenth century. In 1882, Goodell published an article in the American Journal of Insanity that called for “castrating all the insane men and spaying all the insane women”.[7]

Did eugenics catch on?

Darwin gained worldwide renown for On the Origin of Species – not everyone agreed with his findings at the time, but almost all people who were interested in science had heard of his theory. As a member of Britain’s upper class, he was compelled to defend his theories from implications of anti-theism, and he did so vigilantly. In 1871, he published a sort-of follow-up volume to his seminal work entitled The Descent of Man – this work took Origin and the theory of natural selection a bit further.

It dealt with the question that was on everyone’s mind after Origin was published: “If all this is true, where does that put us (humans)..?” Descent was a book that dealt with the implications of evolution and natural selection as they directly related to humans. In this work, Darwin gave a direct nod to eugenics, stating: “We civilised men…do our utmost to check the process of elimination; we build asylums for the imbecile, the maimed and the sick. Thus the weak members of society propagate their kind.”[8]

Eugenics became immensely popular prior to the Second World War. Galton’s ideas were praised widely among top scientists and policy makers in Britain, the United States, and the Scandinavian countries. Many well-known historical personalities were proponents of eugenics, such as American president Teddy Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Helen Keller, and U.S. president and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize Woodrow Wilson. These were dark times – WWI had just ended, 38 million people were dead and Europe was left in ruins, the U.S. was going through the Great Depression – world leaders were grasping at straws for answers to these societal hardships. The philosophy of eugenics made sense to these world leaders trying to rebuild their respective societies into something better than what had come before, but none of them could’ve seen what horrors would result from this type of thinking.

Adolf Hitler took negative eugenics to its horrific, ultimate realization. Even before the horrors of the Holocaust, Hitler and his followers took eugenic philosophies beyond their nineteenth-century ideals – even claiming that the “Aryan race” were not only superior to other races, but actually descended from gods. There are many works that study the cult-like and occult roots of white supremacy, but most historians think them speculative, at best.[9] After WWII ended, and the horrors of German concentration camps became known to the general population, almost all of European and American society sought to distance itself from “eugenics”. This does not mean, however, that studies and experiments with eugenic undertones vanished – similar ideologies pervaded scientific studies and experiments all the way into the 21st century.

Conclusion

While eugenic policies seem outdated and ridiculous to us in modern times, we should consider that such policies have carried on well into the late-twentieth and even twenty-first centuries. Native American women continued to be sterilized up into the 1970s.[10] In 2013, it was also reported that 148 female prisoners in California were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 in a program these prisons claimed was voluntary. Subsequent investigations found that the incarcerated did not legally give consent to undergo these procedures.[11] These examples are only in the United States – there are countless other such human rights abuses in other countries that still continue on, even today.[12]

Francis Galton’s findings were extremely prejudiced and biased, but we should be careful not to discredit his entire study because of these unfortunate facts. Some of his findings were, in fact, spot on. For example, in the closing paragraph of Hereditary Genius, he states: We must not permit ourselves to consider each human or other personality as something supernaturally added to the stock of nature, but rather as a segregation of what already existed, under a new shape, and as a regular consequence of previous conditions.

This type of thinking was way ahead of its time in 1869. Suggesting that each human being was not a special, original creature molded and created by God himself, in his own image, was not a popular viewpoint during the Victorian era. Just like his cousin Darwin before him, Galton had to defend his gentlemanly status against accusations of materialism and atheism. Ultimately, neither man denounced his faith or thought his scientific findings to conflict with his religious beliefs. To this very day, billions of religious believers still seek to reconcile their faith with accepted science, and depending on whose opinion you may take, they have been largely successful.

Works Cited

- ↑ Google Search, accessed June 16, 2017, https://www.google.com/search?q=eugenics%2Bdefinition&oq=eugenics%2Bdef&aqs=chrome.0.0j69i57j0l4.2214j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

- ↑ See: Darwin and Gray, The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication.

- ↑ Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, 48.

- ↑ Darwin, On the Origin of Species.

- ↑ Galton, Hereditary Genius, v.

- ↑ Seligman, “Good Breeding.” 53.

- ↑ Goodell, The American Journal of Insanity, 38:295.

- ↑ Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 168.

- ↑ See: Goodrick-Clarke, The Occult Roots of Nazism.

- ↑ Lawrence, “The Indian Health Service and the Sterilization of Native American Women.”

- ↑ Stern and Platt, “Sterilization Abuse in State Prisons: Time to Break With California’s Long Eugenic Patterns | HuffPost.”

- ↑ Ko, “Unwanted Sterilization and Eugenics Programs in the United States | No Más Bebés | Independent Lens | PBS.”