What was the Comstock Act

The Comstock Act (1873), or the “Act of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use” was a statute designed to make the transmission of “obscene material” by mail a crime. The Act had far-reaching implications for Americans during the time it was enacted (mostly through the 1930s, but some remnants of the Act remained until much later). The Act, which is named after its primary champion and architect Anthony Comstock, marks an important attempt to regulate American behavior at a time when society was rapidly changing.

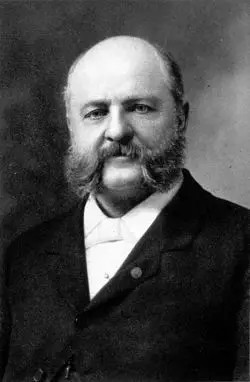

Anthony Comstock

Anthony Comstock was born in Connecticut in 1844. His father was a farmer and his mother was very religious. He was very young when she died, but her religious fervor lived on in him. Comstock believed God knew when people were tempted, so it was better to abstain from all impure thoughts.

Comstock enlisted in the military during the American Civil War, but since he was stationed away from most of the fighting, he entertained himself by launching private initiatives against tobacco, gambling, alcohol, and other practices among his fellow soldiers. He also participated in the Christian Commission—which was created by the Young Men’s Christian Association. The Christian Commission sent missionaries to battlefields to help soldiers remain moral.

After the War, Comstock moved to New York where he was shocked to see obscene material everywhere. Working off his previous reform initiatives, he engaged in his own crusade. Purchasing obscene material and using it as evidence of a violation of an existing—albeit mostly unenforced—1865 obscenity law.

Towards the Comstock Act

After two legal defeats, Comstock founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV). The organization's aim was to supervise, regulate, and control society's access to materials and other influences that Comstock thought to be immoral. The NYSSV was backed by wealthy philanthropists, and Comstock used their money to lobby Congress to pass the An Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use, or Comstock Act for short. Here, he was successful.

The Comstock Law made it a crime to sell or distribute materials that could be used for contraception or abortion, to send such materials or information about such materials in the federal mail system, or to import such materials from abroad.

This Act designated that a special agent is appointed by the postal service for enforcement, and Comstock was the first person to serve in this post. He held that position for some 40 years.

Through this position and through the Society for the Suppression of Vice which he created, he and his colleagues rigorously enforced the Comstock Law, making it very difficult for the late 19th and early 20th century advocates of birth control to send out birth control information.

Excerpt from Comstock Act

Be it enacted… That whoever… shall sell… or shall offer to sell, or to lend, or to give away, or in any manner to exhibit, or shall otherwise publish or offer to publish in any manner, or shall have in his possession, for such any purpose or purposes any obscene book, pamphlet, paper, writing, advertisement, circular, print, picture, drawing or other representation, figure, or image on or of paper or other material, or any cast instrument, or other article of any immoral nature, or any drug or medicine, or any article whatever, for the prevention of conception, or for causing unlawful abortion, or shall advertise the same for sale, or shall write or print, or cause to be written or printed, any card, circular, book, pamphlet, advertisement, or notice of any kind, stating when, where, how, or of whom, or by what means, any of the articles in this section… can be purchased or obtained, or shall manufacture, draw, or print, or in any wise make any of such articles, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and on conviction thereof,… he shall be imprisoned at hard labor in the penitentiary for not less than six months nor more than five years for each offense, or fined not less than one hundred dollars nor more than two thousand dollars, with costs of court.

Effects of the Comstock Act

The law was ambiguous and came down to the banning of any material that Anthony Comstock considered obscene. Those convicted could face 5 years of imprisonment with hard labor, even a fine up to $2,000—which after accounting for inflation would amount to over $39,000 today. One of the main targets under the Comstock Act were advertisements for abortionists or devices or medication to produce an abortion, though Comstock targeted novels that were too risqué, and even medical textbooks.

The law may have been intended as a measure to protect children against erotica, but it also included material about contraceptive devices, materials, or information about abortion, so it may have also been an effort to curb the rising practice of Free Love. Industrialization in the nineteenth century resulted in a vast array of medicines, devices, tonics, and medicines for women’s health. At the same time, Goodyear’s rubber vulcanization process—which allowed rubber to remain intact in heat and cold—transformed other contraceptive devices. These once haphazard prophylactics constructed from various linens, intestines, or other raw materials, contraception developed into its own systematic industry. Soon, the vulcanization process opened the door to a variety of other rubber contraceptive devices, including IUDs, diaphragms, and douching syringes.

These early, mass-produced contraceptives were available through mail order or over the counter. Catalogs circulated by B.F. Goodrich, Goodyear, Sears, Roebuck, and wholesale drug supply houses such as McKesson and Robbins advertised a full line of contraceptives from intrauterine devices to pessaries, douching syringes, sponges, and cervical caps. A company was reputable if they only sold its products to licensed doctors and druggists.

Increased printing technologies also allowed for information about birth control and abortion to be widely disseminated. Advertisements for contraceptives, doctors who treated women’s conditions, as well as those for patent medicines to induce miscarriage all made sex more visible.

It was in this context of heightened visibility that Comstock emerged. Notwithstanding Comstock’s best efforts, manufacturers and advertisers of abortifacients and other contraceptive devices found methods of eluding censorship—for example, putting warning labels on products that urged pregnant women not to use them because it might induce a miscarriage. By reading between the lines, women would know that this particular product could assist them with their condition.

The Comstock Act, in many ways, was a response to a number of social changes that were occurring: the expansive power of the federal government after the civil war, urbanization—more people moving to cities--, access to cheap print material, the down of photography, the rise of affordable birth control, and an influx of Southern and Eastern Europeans—who many native-born whites saw as members of distinct, and inferior races.

Towards the end of his career, Comstock claimed that over the course of just ten years he had confiscated 202,204 pictures, 21,150lbs of books, and 63,819 contraceptive devises.

References

Anna Louise Bates, Weeder in the Garden of the Lord: Anthony Comstock's Life and Career(Lanham: University Press of America, 1995)

Nicola Beisel, Imperiled Innocents: Anthony Comstock and Family Reproduction in Victorian America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998)

Anthony Comstock, Traps for the Young, Robert H. Bremner, ed. (New York: Belkanp, 1967).

Andrea Tone, Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America (New York: Hill & Wang, 2002)