How did the United States react to France's takeover of Mexico during the Civil War

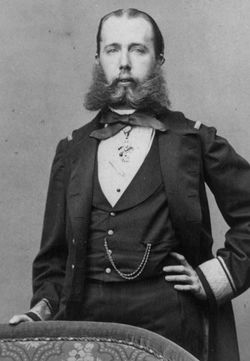

In 1862, French Emperor Napoleon III maneuvered to establish a French client state in Mexico, and eventually installed Maximilian of Habsburg, Archduke of Austria, as Emperor of Mexico. Stiff Mexican resistance caused Napoleon III to order French withdrawal in 1867, a decision strongly encouraged by the United States as it recovered from its Civil War weakness in foreign affairs.

Earlier, during the Civil War, U.S. Secretary of State William Henry Seward followed a more cautious policy that attempted to keep relations with France harmonious and prevent French willingness to assist the Confederacy. Consequently, Maximilian’s government rebuffed Confederate diplomatic overtures.

Civil War in 1857 destabilizes Mexico

In 1857, Mexico became embroiled in a civil war that pitted the forces of Liberal reformist Benito Juárez against Conservatives led by Félix Zuloaga. Conservatives exerted control from Mexico City, and the Liberals from Veracruz. The United States recognized the Juárez government in 1859, and in January of 1861, Liberal forces captured Mexico City, greatly strengthening Juárez’s position and legitimacy. However, continued instability had coincided with growing foreign debt that was increasingly difficult for the Mexican government to pay. Secretary of State Seward offered a plan that would provide mining concessions in exchange for American loans.

In the event that the debts were not repaid, Mexico would agree to the cession of Baja California and other Mexican states. The terms of the loan were onerous to the Mexican government, but U.S. diplomat Thomas Corwin successfully negotiated a treaty with Mexican representative Manuel Maria Zamacona. Ultimately, though, the U.S. Congress rejected the treaty on grounds that it would drain money from Civil War expenditures.

European forces invade Mexico and install Maximilian the Archduke of Austria as Emperor of Mexico

With no other options, Juárez suspended payments on Mexican debt for two years. In response, representatives from the Spanish, French, and British governments met in London, and on October 31, 1861, signed a tripartite agreement to intervene in Mexico to recover the unpaid debts. European forces landed at Veracruz on December 8. Juárez urged resistance, while Conservatives saw the intervening forces as valuable allies in their struggle against the Liberals.

Although the British and Spanish governments had more limited plans for intervention, Napoleon III was interested in reviving French global ambitions, and French forces captured Mexico City, while Spanish and British forces withdrew after French plans became clear. In 1863, Napoleon III invited Maximilian, Archduke of Austria, to become Emperor of Mexico. Maximilian accepted the offer and arrived in Mexico in 1864. Although Maximilian’s Conservative government controlled much of the country, Liberals held on to power in northwestern Mexico and parts of the Pacific coast.

In response to these actions, Secretary of State Seward issued statements of disapproval, but the U.S. Government was unable to intervene directly because of the American Civil War. Moreover, both Seward and U.S. President Abraham Lincoln did not want to further antagonize Napoleon III, and risk his intervention on the side of the Confederacy. The U.S. Government also rejected overtures from other Latin American countries for a pan-American solution to the conflict. However, the Mexican Minister to the United States, Matías Romero, worked carefully to build American support for Mexico. Seward soon began to show increased support for Juárez’s government.

Related Articles

- Why did the United States start the Mexican American War

- What Caused The Economic Panic Of 1837

- Why did Andrew Jackson want to destroy the Bank of the United States

- Why did the United States begin directly electing Senators in 1913

- What convinced Americans during the 1918 Flu Pandemic to wear masks

- What was the Fatty Arbuckle Scandal and how did it influence Hollywood

- What is the history of the United States Capitol Building

Mexico overthrows Maximilian

The end of the American Civil War in 1865 coincided with the beginnings of success for Juárez’s forces against Maximilian’s. Maximilian, ill-informed on Mexican affairs prior to his arrival, alienated his Conservative allies by attempting to adopt more Liberal policies, while he failed to win over Liberals, who saw him as a tool of French interests and Mexican Conservatives. In 1865, Liberal military victories made Maximilian’s position increasingly difficult. Meanwhile, U.S. Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Philip Henry Sheridan bypassed Seward and began covert support of Juárez along the Texas-Mexico border. By then, the intervention in Mexico had grown unpopular with the French public and was an increasing drain on the French treasury.

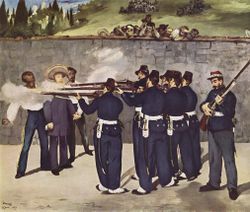

On January 31, 1866, Napoleon III ordered the withdrawal of French troops, to be conducted in three stages from November 1866 to November 1867. Seward, who had earlier been more cautious, warned the Austrian Government against replacing French troops with its own forces, and the threat of war convinced the Austrian government to refrain from sending Maximilian reinforcements. Without European support, Maximilian was unable to retain power. His capture by Mexican forces, court-martial, and sentenced to be executed, marked the end of direct European intervention in Mexico. Seward hoped that U.S. support for Juárez would improve relations with Mexico, but as part of Seward’s broader strategy of U.S. expansion, he hoped that the improved relations would eventually convince Mexico to join the United States.

Conclusion

Throughout the period of French intervention, the overall U.S. policy was to avoid direct conflict with France, and voice displeasure at French interference in Mexican affairs, but ultimately to remain neutral in the conflict. After 1866, Seward provided more direct support for Juárez, while French willingness to withdraw de-escalated Franco-American tensions. Although U.S. support for Juárez improved U.S.-Mexican relations temporarily, disputes over policing of the border under Secretary of State William Evarts would erode the goodwill built during Seward’s tenure.