How Did Art Propagate Slavery in 19th Century America

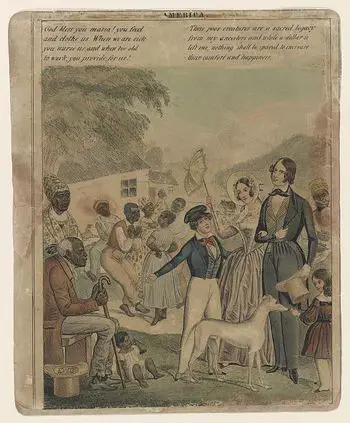

The Antebellum period in America gave rise to political tension focusing on the issue of slavery. Politicians, large planters, orators, and activists engaged in heated and often violent debates as to the merits of “owning” a human being. The political, social, and economic angles were argued with each side offering its own spin on the topic. The importance of art as propaganda cannot be omitted when discussing Antebellum America. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1858 in an effort to illuminate the horrors of slavery. Nearly two decades earlier; however, Edward William Clay’s 1841 drawing, America, was a response to the increased abolitionist movement in the North. Clay’s intent was promote the idea that slavery was good for slaves. The significance of this piece however, is not in the meaning itself; rather the importance lies in Clay’s intended audience. America attempted to convey a message to abolitionists and working-class members of the North---both black and white---that the “peculiar institution” of slavery was preferable to eking out a living in northern factories.

Meaning of the Drawing

On its surface, America is a well-drawn depiction of the conditions under which slaves lived in 1841.[1]The primary meaning of this drawing is that slaves were content with their living conditions and that slave owners were magnanimous in their concern for their slaves’ well-being. The slave figures in the drawing are shown smiling and dancing; conveying the message of happiness and satisfaction. The slave owner, who has removed his hat in the presence of his slave, expresses deep concern for his elder slave and vows to do all in his power to address his needs. The overall theme of the picture is that slaves were well cared for, happy with their lives, and had no fears regarding their futures. The secondary meaning is quite different.

Through his art, Clay created a sign; a symbol that made the statement, “slavery is good for slaves.” To be a successful propagandist, Clay needed an audience, as a sign without a signifier is useless. Clay’s intent was to show the working-class citizens of the northern states that slavery was not only good for slaves, but was preferable to the manner in which people of the North lived. This depiction was published in a magazine of the period---Harper’s--- and was therefore directed at an audience. Without an audience who held preconceived or opposing notions regarding slavery, the drawing had primary meaning only to the artist. Clay’s target was an audience composed of northern, working-class citizens.

Conditions in the North

Factory workers in the northern United States did in fact work under harsh conditions for meager wages. Employers in Antebellum America offered no medical or retirement benefits to workers. Each employee was responsible for his own well-being and that of his family. For most workers this meant feeding, housing, and clothing their families with a pittance of a wage. The work days were long and strenuous and mainly consisted of six day work weeks. Old age and illness forced most to take that last small step into poverty. The conditions under which these people lived contrasted significantly with those portrayed by pro-slavery propagandists. The message conveyed in Clay’s piece was echoed sixteen years hence by Virginia writer, George Fitzhugh. The author penned, “The Blessings of Slavery” in 1857 to assert his belief that “‘Negro slaves of the South are the happiest, and, in some degree, the freest people in the world.’”[2]He believed that workers in free society were in fact themselves “slaves” of the factories. Looking at Clay’s drawing, it is easy to see why this propaganda may have had its desired effect. Each individual character of the picture depicts contentment. The surroundings and people, coupled with the attached text paint a picture of a joyous and unburdened life.

Clay portrays the surrounding landscape as clean and inviting. The grounds are free of trash and clutter and the cabins appear as warm and solid structures. He, of course, was well aware of the conditions under which people lived in densely populated urban cities. The tenements, which mainly comprised the immigrant and working class sections of cities such as Boston and New York, were shoddily built. The crowded, garbage filled streets were busy with activity and littered with vagrants and transients. Families of six and eight people were packed into one-bedroom flats that were cold fire traps. It was to those people whom Clay hoped to speak. For they were the people who were toiling fifteen hours a day yet were still cold and hungry.

Clay’s slaves were depicted as the opposite of the reality endured in the cities. The drawing presents the audience with happy slaves dancing on a sunny day. Hale and hearty, they are the embodiment of good nutrition and adequate rest. A healthy, barefooted child sits on the warm earth in a clean and well-fitting dress. The white woman, presumably the slave owners wife, shields her eyes with a parasol; indicating a warm and sunny climate. Again, this is in stark contrast to the all-too-real conditions faced by factory workers in the North. Workers in Chicago’s packing houses or Lowell’s factories endured frigid winters and sparse rations. Their children often faced serious illness due to poor nutrition and lack of medical care. The adults were too exhausted at the end of a work day to engage in dancing and singing. They were alone in the effort to support their families contrary to what Clay wanted one to believe about slaves.

Though Clay’s concept is conveyed through a drawing, he supplements the significance with the use of text. The highlight of the piece is the fictional dialogue between the elder slave and his “massa.” He bestows the blessing of God upon the white man for feeding and clothing him and for the assurance that he will be well cared for in sickness and old age. The “massa,” in turn, betrays his stoic exterior by professing his compassion for his property. With benevolence and sincerity, he vows that “if a dollar is left” he will care for and provide comfort to “these poor creatures.” Succinctly put, slaves of the South had a benefactor or guardian while the workers of the North were left to their own devices. This summarizes the message of the entire piece: slavery is good for slaves and those of free society can never understand the “community of interest” that is shared between slaves and their owners.[3]A message such as this is conveyed as much through what is not presented by Clay as through what is shown to the audience.

Reality

As it is not the purpose of this essay to debate whether slavery was good or bad, it is sufficed to say that Clay’s depiction is not accurate. Slaves did in fact work under grueling conditions and the watchful eye of an overseer. Their cabins were often merely cold and dark shacks and their nutrition was less than healthful. A slave did not receive the courteous sign of respect of a white man removing his hat in the presence of a black man. Slaves did not dance and sing in the middle of the day when their master approached. Their clothes were ill-fitted and though they tried, were unable to be kept clean. Conditions such as these were on par with those of free society; the difference of course being the word, “free.”

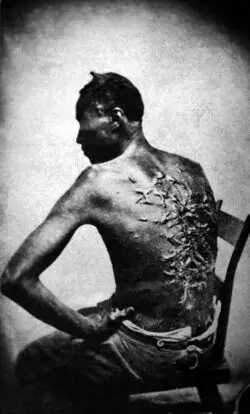

Gordon, a slave who escaped from a Louisiana plantation in 1863, successfully reached a Union camp near Baton Rouge. He was photographed and given a complete medical examination. Gordon’s photograph attests to the harsh and inhumane punishments suffered by slaves. The scars on his back speak volumes regarding the inaccuracy of Clay’s drawing. Further, slave owners did not address the question of why slaves became fugitives. If, as Clay asserts through his art, slaves were satisfied with their station in life, why did they risk their lives to leave? Gordon was certainly not the only person to receive such treatment. Clay’s drawing was more effective in its omissions than in what it actually depicted.

Conclusion

The intended significance or message put forth by Clay, was not just that slavery was good for slaves; rather, the “peculiar institution” in and of itself was superior to the economic institutions of the North. In order to attain his communication goal, Clay needed an audience comprised of individuals with views opposite to those depicted in the drawing. As with all pieces of propaganda, Clay attempted to communicate his agenda not only as something positive, but something superior. For something to be superior, it must be superior to something else. In this case, Clay compared societal institutions. He was not weighing the positive or negative effects of slavery vs a free society; he leaves that for his audience. However, by portraying his belief that slavery is a positive institution he attempted, by omitting certain aspects, to sway the views of his opponents.

References

- Jump up ↑ Edward Williams Clay, America, 1841, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. For further information regarding the work of Clay, see the Library of Congress website, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b3616/.

- Jump up ↑ George Fitzhugh, “The Blessings of Slavery,” (1857), quoted in Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty!: An American History, vol. 1, 2nd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 390.

- Jump up ↑ Fitzhugh, “The Blessings of Slavery,” in Foner, 390.

Admin, Costello65 and EricLambrecht