Who integrated the NBA

Sports, like American society, was segregated well into the 20th century. In many ways professional sports was the face of race in the cultural fabric. African-American athletes competed in their own separate, but unequal, professional leagues and little was done to challenge the status quo. Branch Rickey, who was the general manager of baseball’s Brooklyn Dodgers, was the first to step up and end segregation in American sports.

Baseball was by far the most popular sport in 1940s America and Rickey was forced to move deliberately and furtively for years. He did tireless background research and interviewed many athletes to find the person who had the character to endure what was certain to be a difficult indoctrination into “white baseball.”

The man he settled on was Jackie Robinson, who was not an obvious choice. Robinson had been an outstanding collegiate athlete at UCLA in California where he starred in the Bruin backfield and was a record-setter in track and field. But he played baseball for only one year and was not very good, batting only .097. [1] After college Robinson served with distinction in World War II and was already a mature man with a grounded sense of himself before signing on to what promised to be a long ordeal with Rickey and the Dodgers.

Rickey started Robinson in organized baseball outside of the United States in Montreal with the Dodgers’ farm team. He orchestrated Robinson’s career carefully until he appeared in the Brooklyn line-up on April 15, 1947. Jackie Robinson’s entry into major league baseball became a watershed in race relations in the United States. An American hero, his number 42 has been retired by every major league team.

Breaking the Color Barrier in Professional Basketball

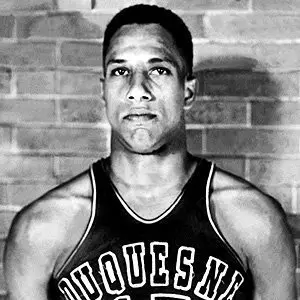

One of the beneficiaries of Robinson’s groundbreaking efforts in baseball was professional basketball. The National Basketball Association was only in its second year when Robinson debuted and a culture of segregation had not yet hardened. But there were still no African-American players in the league when the owners convened for a player draft on April 25, 1950. In the second round, with the 14th pick of the draft, Boston Celtics owner Walter Brown picked Chuck Cooper who had earned All-American honors at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. Startled, a fellow owner blurted out, “Walter, don’t you know he’s a colored boy?” Brown responed, “I don’t care if he’s striped, plaid or polka dot."[2] Race relations had advanced so far in the three years since Robinson’s baseball debut that the Boston papers did not even see the need to include Cooper’s race in its covering of the draft.

In the ninth round of the 1950 draft the Washington Capitols selected Earl Lloyd from West Virginia State University and in the next round Washington added guard Harold Hunter from North Carolina College to the roster. The next day Hunter signed a contract to become the first official black player in the National Basketball Association. [3]

Hunter however did not make the Capitols team and never suited up for an NBA game. He stayed in basketball and became a respected coach. Later in his career he became the first African-American to take charge of an international team when he coached a team of American Olympians on a tour of Europe and the Soviet Union.

Not One, but Three “Jackie Robinsons”

Before either Cooper or Lloyd inked a contract the New York Knicks reached an agreement with Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton of the Harlem Globetrotters. So when NBA teams broke training camp for the 1950-51 season there were African-American players on the Capitols roster, the Celtics roster and the Knicks roster. This trio would make up professional basketball’s “three-headed” Jackie Robinson.

Of the three, Clifton’s background most closely resembled Robinson’s. He was not a newly minted college athlete but a seasoned player of 28, the same age as Robinson when he first played with the Dodgers. Both hailed from the rural South but moved with their families to big cities to spend their formative years. Both played multiple sports in college and Robinson and Clifton were each veterans of the United States military and the professional Negro leagues.

As it turned out Lloyd was the first black player to see action in an NBA game, scoring six points and grabbing ten rebounds off the bench in a Halloween night game against the Rochester Royals. Like the ennui that greeted the drafting of African-American players, there was no mention of racial history in the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle write-up of the 78-70 Capitols win.[4]

Cooper saw his first game action the next night and two days later Clifton played his first game. Once again, there was no mention of race in any press account of the games. Basketball had made a quiet and uneventful transition to integration.

The Aftermath

The Capitols did not last out the season, folding in January of 1951. Lloyd enjoyed better luck, although he was drafted into the Korean War before coming back to play several more seasons in the NBA. In 1955 Lloyd and teammate Jim Tucker became the first African-Americans to play on a championship team, the Syracuse Nationals.[5] He retired in 1961 and was named the second African-American head coach in the National Basketball Association in 1973. He suffered through a 22-55 season that year with the Detroit Pistons.

Chuck Cooper, the original draftee, also enjoyed a lengthy NBA career. He played until 1956, appearing in 409 games and scored 2,725 points. After his professional playing days ended Cooper went back to school, earned a Masters degree in Social Work from the University of Minnesota, and returned to Pittsburgh where he became the city’s first black director of parks and recreation. [6] When he attended Duquesne basketball games he could see his retired #15 hanging from the rafters.

Clifton was the only one of the pioneering trio to earn All-Star honors like Robinson had done in baseball. Thirty-four years old at the time in 1957, Sweetwater was the oldest player in NBA history to be named as a first-time All-Star. After that season, he retired with lifetime marks of 10.0 points and 8.2 rebounds per game. [7] In 2014, Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton joined Earl Lloyd as basketball racial trailblazers inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Related DailyHistory.org Articles

References

- Jump up ↑ Simon, Scott, “UCLA’s Legacy in the Jackie Robinson Story,” Los Angeles Daily News, April 11, 2013

- Jump up ↑ Foster, Frank,Sweetwater: A Biography of Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton, BookCaps StudyGuides, 2014, Introduction

- Jump up ↑ Broussard, Chris, "3 Pioneers Hailed for Breaking Color Line," The New York Times, November 1, 2000.

- Jump up ↑ Howell, Dave, “Six Who Paved the Way,” NBA.com

- Jump up ↑ Goldstein, Richard,”Earl Lloyd, N.B.A.’s First Black Player, Dies at 86," The New York Times, February 27, 2015.

- Jump up ↑ Manheim, James M., “Charles "Chuck" Cooper Biography - Played for West Virginia State College and Duquesne, Formed Friendly Relationships with Celtics Players,” http://biography.jrank.org

- Jump up ↑ Brown, Clifton,"Sweetwater Clifton, 65, Is Dead; Was Star on 50's Knicks Teams," The New York Times, September 2, 1990