What is the history of impeachment in the United States

Impeachment is a two-part process that allows state or federal legislatures in the United States to remove either an elected or appointed official from office for "high crimes and misdemeanors." The process begins in the state or federal house of representatives. After a trial, the official then faces an impeachment vote by the lower house. House votes typically only require a majority vote for impeachment. If the house impeaches the official, it is referred to as the state or federal senate.

The state or federal senate then decides if that official will be convicted and removed from office based on the findings of the House during the impeachment process. Unlike the vote in the house for impeachment, most senates must have a 2/3 majority to remove an official from office. Impeachment and conviction represent a critical part of the checks and balances envisioned by the Constitution and also by local and state laws. While presidential impeachments have been rare, but judges, congressional members, governors, and others have been impeached and convicted while holding office.

Additionally, while impeachment and convictions are often compared to trials, they are inherently political. Politics can play an as large or even greater role than the evidence that is presented.

Early Impeachments in the 18th and 19th Century

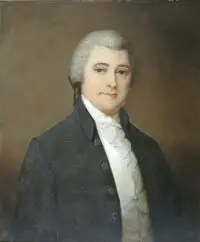

Impeachments are the first step to remove by the lower legislative house when an alleged crime has been committed by an official, often during their tenure. History also shows that it is possible to remove an official for a crime committed before entering office. William Blount (Figure 1) was the first elected official who was impeached. He was a senator from Tennesse and in 1797 was impeached for conspiring with Great Britain to wage war and capture Spanish territory so that his real estate ventures would benefit. The senator was a known land speculator who had purchased the territory in western Tennessee and other surroundings. He had over purchased and was in debt. Thus to raise the land's value, he tried to have Great Britain seize territory in Louisiana from Spain, as colonists might be forced to move to areas where he owned land.

This decision backfired on him, and the House of Representatives tried to impeach him for conspiring with a foreign state to launch a war between Spain and Great Britain. Still, ultimately the Senate refused to accept the House's oversight and decision. The Senate did remove him anyway, but during this early history of the United States, the Senate wanted more separation from the House.[1]

During the time between the founding of the United States and the Civil War, there were just three impeachments: judges. Two of these were local district Judges, John Pickering and James Peck, but one was a chief justice (Samuel Chase). Most of the issues against them had to do with abuse of power and drunkness in the case of John Pickering. In the case of Samuel Chase, Thomas Jefferson had found him obstructionist in his political agenda after the 1800 election. Although a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, Samuel Chase had been known for irregular behavior, including using his position in the Continental Congress to improve his business dealings. Washington appointed him to the Supreme Court, and during the time of Jefferson, the Supreme Court was seen as a threat to seizing too much power.

In 1803, impeachment articles were brought up against him, dealing with the justice's behavior against Thomas Cooper and others. Thomas Cooper was tried under the Alien and Sedition Acts for criticizing John Adams, the previous president. Samuel Chase repeatedly riled against Thomas Cooper, a close friend to Thomas Jefferson, leading to Thomas Jefferson trying to remove Samuel Chase from office because he saw him overstepping his bounds. Ultimately, this proved unsuccessful for Jefferson, and Chase was formally acquitted by the Senate in 1805.[2]

During the Civil War, there was a successful impeachment of a district judge (West Humphreys) for supporting the South in 1862. However, the trial of Andrew Johnson in 1868 proved to be the first impeachment trial against a sitting president. Andrew Johnson, never a strong believer in giving rights to former slaves came to office as vice-president to Lincoln in 1864 as part of a national unity ticket that had him, a Democrat, served with Lincoln, a Republican. During the early reconstruction years, Congress repeatedly refused the Southern states' return to power that Southern states tried to reinstate into the Union. Johnson was sympathetic to the Southern states, setting the stage for conflict with Congress. They eventually limited his power to shape his cabinet, bypassing the Tenure of Office Act that prohibited Johnson from firing his cabinet members.

After Johnson tried to fire his Secretary of War (Edwin Stanton), Congress acted and impeached him. Ultimately, Johnson survived and was acquitted, although he was not re-elected later in 1868. Interestingly, Johnson survived because Congress was fearful that Benjamin Wade, a so-called radical Republican, would push through legislation such as women's suffrage (something not acceptable to most politicians in the 1860s). In the 1870s, two more impeachments occurred, with one district judge (Mark W. Delahay, for drunkenness; acquitted but resigned) and the first cabinet member (William W. Belknap; Secretary of War; acquitted but resigned) impeached.[3]

Impeachment in the 20th Century

Impeachment throughout the 20th century focused on judges, mostly district judges, such as Charles Swayne (1905), George English (1926), and Halsted Ritter (1936). Most of these revolved around abuse of power and corruption. One of the more noteworthy impeachments was Robert Wodrow Archbald, who was on the Commerce Court. He was convicted in 1913 and removed from office for taking gifts to sway his decisions. He was given favorable railroads and real estate deals in exchange for decisions. He was eventually convicted in January 1913, despite his repeated attempts to claim innocence. While the 1920-1930s saw three impeachment cases, there were no impeachment cases between 1936-1986, the longest stretches in US history without any impeachment trials of any government official at the federal level. In the 1980s, there were three impeachment trials of judges (Harry E. Claiborne, Alcee Hastings, and Walter Nixon), all of whom were convicted and removed from office as district judges. These cases had to do with tax evasion, bribery, and perjury.[4]

The next big federal case was against President Bill Clinton in 1998 due to the sexual harassment case concerning the Paula Jones investigation, which also included the Monica Lewinsky affair. This was the first impeachment of a sitting president since Andrew Johnson. The result required a two-thirds majority for his conviction, with Bill Clinton just surviving in a mostly partisan vote on February 12, 1999, that saw the Senate vote 50 for and 50 against concerning the charge of obstruction of justice and 55 (not guilty) to 45 (guilty) for perjury. After the acquittal of Clinton, in 2009 and 2010 respectively, Samuel B. Kent and Thomas Porteous, who were district judges, also faced impeachment. Both of them were effectively removed from office due to the proceedings, although Samuel Kent was acquitted.[5]

State Level Impeachments

Impeachments have also occurred, generally more frequently, at the state level, often involving governors or state officials and state judges. The first governor to be impeached was Charles L. Robinson from Kansas, in 1862, who was impeached due to his rivalry with James Lane. Robinson, along with John Robinson and George S. Hillyer, who were the Secretary of State and Auditor of the state, were all impeached.

This was effectively an attempt to overthrow the Kansas government at a time when elections were highly disputed in Kansas and the previous decade's controversial statehood of Kansas lingered in memory. While the 1862 impeachment of Robinson of Kansas was the first impeachment of a governor, although he was acquitted, the 1870s saw a series of impeachments against governors acrimonious reconstruction years of governors elected or selected in southern states. Governors from Florida, North Carolina, Louisiana, and Mississippi were all impeached in the 1870s, with only the governor of Florida (Harrison Reed) surviving his impeachment proceedings.[6]

In 2009, one well known recent case of a governor's impeachment revolved around Rod Blagojevich (Figure 2), who tried to sell and solicit bribes of the Senatorial seat occupied by Barack Obama to become president after 2008. This was notable in being among the fastest impeachment proceedings in history, where the crime and impeachment trial occurred about one month apart. In more recent times, state officials' most notable impeachment occurred in 2018, with the West Virginia Court of Appeals judges impeached due to excessive spending. These impeachment trials have not fully concluded as of early 2019.[7]

Conclusion

Almost all federal level impeachments have been against judges, often with cases related to corruption or behavior that involves illegal payments and perjury. At the state level, governors have become impeached only from around the Civil War and until today. In the 1870s, governors were tried in southern states to be seen as anti-southern or supported by the US government to enforce Reconstruction. More recently, Rod Blagojevich, governor of Illinois, and state Supreme Court justices in West Virginia have faced impeachment for corruption-related charges.

References

- Jump up ↑ For more on these early trials, see: Melton, B. F. (1998). The first impeachment: the constitution’s framers and the case of Senator William Blount (1st ed). Macon, Ga: Mercer University Press.

- Jump up ↑ For more on Samuel Chase and his case, see: Rehnquist, W. H. (1999). Grand inquests: the historic impeachments of Justice Samuel Chase and President Andrew Johnson (1. Quill ed., reissued). New York: Quill/Morrow.

- Jump up ↑ For more on impeachments that include Andrew Johnson and the late 19th century, see: Harvey, A. L. (2014). A mere machine: the Supreme Court, Congress, and American democracy. Yale University Press.

- Jump up ↑ For more on these impeachments, see: Gerhardt, M. J. (2000). The federal impeachment process: a constitutional and historical analysis (2nd ed). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jump up ↑ For more on Clinton and the later impeachments, see: Lichtman, A. J. (2017). The case for impeachment (First edition). New York: Dey St., an imprint of William Morrow.

- Jump up ↑ For more on the first state-level impeachments, see: Snell, G., & Shea, W. (1991). Hysterically historical. Red Fox.

- Jump up ↑ For more on these recent cases, see: Tseng, M. (2018). The Politics of Impeachment. Westphalia Press.

Updated December 7, 2020