Was William Tell a real person

Every country has its national heroes, who embody the spirit of the nation. Switzerland’s national hero is William Tell, who was seen as the embodiment of the nation’s love of liberty and its struggle for freedom. Tell was not only a hero in Switzerland but throughout the world, he is seen as a symbol of freedom and even of revolution.

His audacious marksmanship when he shot an apple off his son’s head is well-known. There have been many works celebrating this hero. He has been the subject of a grand opera by Rossini and a classic play by Schiller. However, the issue of the historicity of William Tell has been controversial. For many centuries there are those who denied that he was a historical figure. There are some, including many Swiss nationalists who claim that he was a real person. This article examines the legend of William Tell and determines if there was a real-life hero by that name or was the bowman only a myth.

Historical context

Modern-day Switzerland was part of the Holy Roman Empire in 1200. In the medieval period global warming, meaning that the Alpine valleys became suitable for livestock and this allowed for the population to grow, rapidly. The Swiss territories or cantons were largely autonomous and only nominally controlled by the German Empire.

However, this was to change with the rise of the Hapsburg dynasty in neighboring Austria. The Hapsburg’s became the most important power in central Europe and also Holy Roman Emperors. Successive Austrian monarchs began to interfere in the internal affairs of the Swiss Canton and threatened their traditional liberty. They even imposed bailiffs and local rulers on the cantons. Like many mountain-people the Swiss were independent-minded, and they resisted what they saw as Austrian oppression.

In 1291 they adopted a federal charter which is still the basis of the Swiss Constitution, and in 1307 several cantons and cities came together to form a confederacy to protect their liberties. The Swiss, who were renowned pikemen, defeated the Hapsburgs at the Battle of Morgarten (1315) and the Battle of Sempach (1366). The cantons were able to expand their territory and later defeated the Dukes of Burgundy (1477), and their territories became the nucleus for the modern state of Switzerland. The context of the William Tell story is Switzerland’s struggle for independence from the Hapsburgs and its emergence as a nation. [1]

William Tell - The Legend

The sources of the story of William Tell are varied. It appears that there were songs and poems about the hero and his exploits from the medieval period. The earliest known account of William Tell, in written form, was from the 1470s. In the same decade, a popular ballad on Tell was also published. The most important source for the legend is the Chronicon Helvetica (1734–36), written by Gilg Tschudi. This Swiss author has given us the definitive version of the story of William Tell.

In Tschudi’s account Tell embarked on a series of heroic adventures beginning in 1307. In the most popular form of the story, William was a renowned herdsman, hunter, climber and had great physical strength.[2] He was famous for his skill with the crossbow. He lived in the canton of Uri, which at the time was governed by the House of Habsburg. The Austrians behaved in a tyrannical fashion, and this led some locals, including Tell to form a conspiracy, aimed at driving them from Uri. He and the other conspirators vowed to resist Hapsburg rule and to restore the lost freedoms of the people.[3]

At this time, a cruel Austrian by the name Gessler was appointed the Hapsburg rulers’ deputy in the town of Altdorf. He placed his hat on a pole, under a tree in Altdorf town square and any person passing it had to bow to it. His hat symbolized Austrian superiority and its domination in Switzerland. [4] One day William Tell and his son were visiting the town and he passed the hat on the pole and refused to bow to it. This was an act of open defiance and Gessler had him arrested and incarcerated.

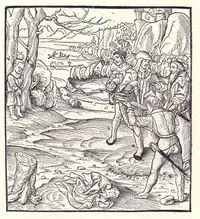

The Austrian had heard that William Tell was a gifted bowman and was also angered by his defiance. He devised a cruel punishment for Tell and his son. Gessler ordered the summary execution of William and his son [5]. However, he gave William Tell a chance to save himself and his son. If the Swiss could shoot an apple off the head of his young son then he would spare their lives.

Tell agreed and the Austrians had his son tied to a post and placed an apple on his head. The Swiss hero then fired his crossbow and split the apple in half without harming the boy. The Austrian then noticed that Tell had two bolts in the bow. The peasant when questioned about the second bolt, told Gessler, boldly, that he wanted to kill him with it. Infuriated, Gessler ordered Tell to be taken to a castle and never released.

As Gessler and his prisoner were making their way across Lake Lucerne to the prison, a storm blew up. The guards implored Gessler to let Tell be freed so that he could take the helm and save them all. They made this request because of the size and strength of their prisoner. Tell was able to steer the boat to shore and he was able to jump ashore before his guards could restrain him, and he escaped.

The spot where he allegedly landed on shore is now the site of a chapel built in his memory. William was able to escape the pursuing Gessler, who pursued him relentlessly. The Swiss hero eventually found refuge, and he laid an ambush for Gessler. He lay in wait for the Austrian near a narrow mountain road. When the Austrian appeared, William aimed and he shot Gessler with his bow.

In another example of marksmanship,’ he killed the Austrian. The feats of the mountaineer greatly inspired the local population, and this joined a popular rebellion against the Austrians. Tell vowed to defend his country and its liberties and many others joined him, this is known as Rütlischwur, and is considered to be of great historical importance because it led to the formation of the Swiss Confederation which was the birth of the Swiss nation.

The rebels were able to drive the Austrians from their land in 1308. According to the most widely accepted story, the marksman later fought in several battles against the Austrians, as the Hapsburgs tried to reconquer the Alpine cantons. It is related that Tell lived to a ripe old age and that he drowned during his rescue of a child in 1354.[6]

How is historically accurate is the story of William Tell?

By the 18th century, William Tell was a very popular figure in Switzerland, so much so that several antiquarians investigated the story. They did not find any evidence that there was such as figure, nor proof that any person shot an apple off a boy’s head. In the 19th century, the Swiss government ordered an official investigation into the authenticity of the story of William Tell.

There was no document found that mentions anyone by that name from the late 1200s and early 14th century.[7] There is no mention of a person shooting an apple off a boy’s head in any record. However, it should be noted that record keeping was very poor at the time, and many documents would have been lost down the centuries. It was pointed out that the first mention of the hero was in the 15th century long after the bowman’s supposed heroics and life.

Many have believed that the story of William Tell and his marksmanship was not historically accurate. Many historians have expressed doubt about the authenticity of the story because crossbows were not commonly used at the time, especially by poor mountaineers such as William Tell. Crossbows in the 14th century were typically very expensive, and only professional soldiers could afford this technology. Crossbowmen were much sought after as mercenaries in the Middle Ages.

Moreover, there is no support for the story that Tell, and others took an oath to free Switzerland. Some believe that a linguistic analysis of the legend to determine if there was a real-life character.[8] Some Swiss scholars have turned to etymology to provide proof of the historicity of the hero. At the time many people took their surname from their home village or territory. Some scholars hold that the name Tell could derive from a district or community. However, these academic exercises do not provide any real evidence for the existence of the Swiss national hero.

The mythological theory

In the 19th century, many academics began the comparative study of myths. They found that many legends, fables, and folktales were similar, and this was because of cultural exchanges between societies. Many researchers who have studied the story of William Tell believe that it is only a myth. There are many similar myths throughout Europe. In these stories, some heroes displayed great marksmanship, and they shot an apple off the head of a person, typically a relative.

There are examples of these stories found in Wales, Denmark, Finland, among others. One theory suggests that the story of William Tell is just the Swiss version of a well-known folktale. It was probably transmitted via trade routes or by migrants, and the story of the great bowman became part of local Swiss culture. This folktale became associated with the Swiss struggle to throw off the Austrian yoke and became so popular, that many assumed that it was based on a real man. This story was told in different ways in many societies throughout the world.[9]

The politics of myth

Despite the almost complete lack of evidence for the existence of William Tell, many firmly believe him to be a real historical figure. In Switzerland, he became the national hero in the 19th century. It seems that the Swiss people needed a hero when the armies of Napoleon occupied its country. He became an embodiment of the nation and its aspirations and showed the people that they could be free. To put it simply the myth was so popular and useful that people wanted it to be true. Moreover, famous artworks, based on the hero, persuaded many people in Switzerland and beyond that Tell was a real person.

Moreover, successive Swiss governments, despite investigations showing that there was no real evidence for the heroes’ existence, continued to pursue policies that treated him as a real-life figure. They erected statues to the man who had purportedly shot an apple off his son’s head and portrayed him as one of the nation's liberators. The Swiss authorities have also used William Tell as a national figure around which people would rally round in times of stress and danger. When Switzerland was threatened in World War One and Two, or during the Cold War, the inspiring story of the bowman was used to boost morale and to promote national unity.[10]

Conclusion

William Tell is not only the national hero of Switzerland but is an international symbol of freedom. The story of the mountaineer has entered into popular culture, and few have not heard about his adventures. It can be stated with certainty that there is no documentary or archaeological evidence for the existence of the hero. There are no records that he shot the apple off the head of his son or stirred the Swiss people to rebellion.

Much of the alleged facts about the hero are probably later inventions. There was no historical figure called William Tell. It seems that the origin of the story was in a myth that was popular in Europe, and which was adopted by the people of the Alpine Valleys. It later was used as a foundation myth, by successive Swiss governments to explain the development of the Swiss Federation.

Further Reading

Puhvel, Jaan. Comparative mythology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987).

Wilson, John. The History of Switzerland (New York, Cosimo, Inc., 2007).

Miller, Douglas. The Swiss at War 1300-1500. No. 94 (London, Osprey Publishing, 1979).

References

- Jump up ↑ Church, Clive H., and Randolph C. Head. A concise history of Switzerland (Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp 45-50

- Jump up ↑ Head, R.C., 1995. William Tell and His Comrades: Association and Fraternity in the Propaganda of Fifteenth-and Sixteenth Century Switzerland. The Journal of Modern History, 67(3), pp.527-557

- Jump up ↑ Müller-Guggenbühl, Fritz. Swiss-alpine Folktales (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1964), p. 18

- Jump up ↑ Head, p 556

- Jump up ↑ Head, p. 552

- Jump up ↑ Müller-Guggenbühl, p 28

- Jump up ↑ Head, p. 551

- Jump up ↑ Head, p. 555

- Jump up ↑ Dundes, A., 1991. The 1991 archer Taylor memorial lecture. The apple-shot: interpreting the legend of William Tell. Western folklore, 50(4), pp.327-360

- Jump up ↑ Ritzer, Nadine. "The Cold War in Swiss Classrooms: History Education as a “Powerful Weapon against Communism. “ Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society 4, no. 1 (2012): 78-94