American Girls in Red Russia: Interview with Julia Mickenberg

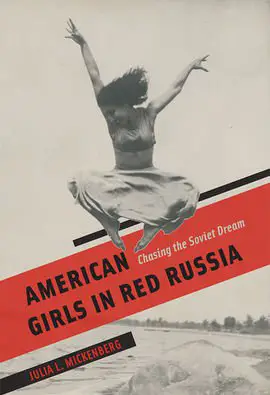

After the creation of the Soviet Union, thousands of Americans emigrated to Russia every year to join in the new communist experiment. Some of these people were excited by the potential of communist state while others will looking for work. Julia L. Mickenberg's new book American Girls in Russia: Chasing the Soviet Dream published by the University of Chicago Press explores the history of the American women who went to Russia looking for adventure, freedom, revolution, work and a new life. After they moved to Russia they found challenges and hardships. Many were disturbed by both the conditions of the country and the treatment of people by the new government. American Girls in Russia explores the stories of these women and provides a glimpse into both their lives and the conditions in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 30s.

Julia Mickenberg is an associate professor in the Department of American Studies at the University of Texas Austin. She writes and teaches about radicalism, women's history, Russia, and children's literature. She has written and edited two previous books: Learning from the Left: Children's Literature, the Cold War, and Radical Politics in the United States and Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children's Literature.

Here is our interview with Professor Mickenberg.

I was certainly aware that some people from the United States such as journalist John Reed moved to the Russia after the revolution, but do you have any idea how many Americans went Russia during this time period?

Thousands of Americans went to the Soviet Union in the first decades following the revolution. Around 16,000 Americans immigrated to Russia in late 1920 and 1921 through ports at Libau and Riga: as the civil war began to die down, despite a blockade by the allies that limited the flow of traffic from North America, many native Russians, especially Russian Jews, who had fled their homeland in the wake of pogroms now returned with hopes that the revolution would mean a better life for them.

Thousands more Americans came between 1921 and 1926 through the Society for Technical Aid to Soviet Russia; many of these folks were idealistic types like John Reed and Big Bill Haywood, the famed Industrial Worker of the World who helped to found the Kuzbas colony. Kuzbas was one of the approximately 25 agricultural or industrial communes made up primarily of Americans and founded during this period (and which I write about in the book). And during the First Five Year plan, or from 1928-1932 — and especially as the Great Depression began to dramatically undercut employment in the United States--upwards of 10,000 people came every year, though most of these people were traveling to the Soviet Union in order to work, rather than going for any ideological reasons.

What type of women were attracted to Red Russia? What were they looking for or hoping to find?

The portrayal of Louise Bryant in the film Reds is pretty accurate. The “Red Russia” of my book’s title (actually the title itself) is from a 1932 news article entitled “American Girls in Red Russia” that describes a wide range of women, some “lending the boys and girls a hand in building Socialism, others seeking husbands among the lonely American engineers, or romantic young Russians, always ready to pay homage to the glamorous American girl.” Among those “barging into the Red capital,” this reporter (herself part of the phenomenon she describes,” notes “stenographers, nurses, dancers, painters, teachers, sculptors, and writers,” which is to say that along with women who accompanied their husbands, the women who interested me were usually pink or white-collar workers who were unmarried or at least self-supporting.

Some, as the article implies, came simply out of a sense of adventure, but more came because they wanted to not just to witness but also to be part of the revolutionary changes. I would call these women feminists, although many of them would have rejected that label because it had come to be associated women who were primarily concerned with gender equality, and these women also cared about class. And more. They were attracted to efforts to refigure the terms of work in the Soviet Union in ways that were designed to put women on an equal footing with men, including generous maternity leave policies, time off for breastfeeding their children during the workday, as well as factory nurseries and public dining halls and laundries that were meant to free women from “domestic drudgery” (even the Bolsheviks assumed that this “drudgery” was properly women’s domain).

They were also attracted to laws designed to reformulate the terms of romantic relationships and motherhood: not only were economically independent women more likely to marry for love rather than for money, but divorce was also simplified, and common law marriages were given the same recognition as those registered with the state. Abortion was not only legalized but also free, and unwed mothers were no longer stigmatized and the category of “illegitimate” children was eliminated. Even women who were “feminists” in that more limited sense of the word were attracted to the “new Russia,” where women gained the vote before their sisters in the United States.

What did they find when they got to the Soviet Union?

When they got to the Soviet Union many women, not surprisingly, faced challenges, but for some, these challenges—or at least a sense that they were suffering for a good cause—were part of the attraction. Even though foreigners had many advantages over Soviet citizens in terms of their access to food and other basic necessities, housing was scarce (especially in Moscow), and what housing there was tended to be small and not necessarily in good repair. Outside of big cities there were bed bugs and primitive facilities. Russian bureaucracy was (and is) infamously difficult to maneuver.

It was evident that most Russians were suffering from shortages of basic necessities, including food, and most foreigners knew about arrests, had heard rumors about violence, and were aware that they were under surveillance. These things became especially evident by the 1930s, but even prior to this time American women who stayed for any length of time commented upon how often innocent people seemed to be unjustly arrested, and people heard about the violence that accompanied the collectivization of agriculture (beginning in 1928), and about the Ukrainian famine, beginning in 1931 and usually seen as resulting directly from Stalin’s policies. After 1935 the paranoia and fear were totally inescapable.

Did these women develop ex-pat communities to help them deal with the challenges they faced in Russia?

Most certainly. The Americans tended to socialize with other English-speaking folks. This meant, primarily, Brits and Australians, but there were also Anglophones from India, Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere. The Quaker House in Moscow served as a center for the American community until about 1930, after which the offices of the English-language newspaper, The Moscow News, which Anna Louise Strong founded in October of that year, served that purpose--until an American embassy opened in 1933, when the United States finally officially recognized the Soviet Union.

While some people such as Emma Goldman were upset by what they saw in post-revolutionary Russia, were there women who did not harbor such feelings and whole heartedly supported the revolution?

There were plenty of people who supported the revolution, but what I found is that most of those people were aware of problems with the Soviet system but hoped that they would be eliminated in the future, or believed that the suffering, violence, and repression were necessary but temporary elements of the transition to socialism. I suppose people in this latter camp could be classed as wholehearted supporters, but my sense is that they supported what might be rather than what was happening in the moment. Still, it is true that they believed in the principles underlying the revolution, and some believed that the ends justified the means.

How did you become interested in this topic? What attracted you to it?

I became interested in this topic through the course of researching my first book, on children’s literature and the Left. Reading scholarship on the US left, the Soviet Union started to seem like an elephant in the room, given its prominence in discourse from the period and its relative absence in scholarship. The positive discussions of the Soviet Union’s programs in support of women and children (discussions that continued even as it became more and more difficult to say good things about the Soviet Union) were particularly striking. But what directly led me to this topic was the discovery in the archive of Ruth Epperson Kennell (a children’s book writer) of material about her experience living communally in a utopian colony in Siberia and attempting to escape “domestic drudgery.” The more I looked at Kennell’s motivation and experience, the more I found other women with similar trajectories.

When did you realize that there were enough resources to turn the story into a book? What resources or archives did you use to tell these women’s stories?

Honestly, it’s been so long since I first began this project that it’s hard to remember whether there was a single moment, but it became clear pretty quickly that there was a lot to be found, especially because I already had surveyed many radical periodicals in the course of researching my first book and I had, through that process, identified sources about Soviet family life, Soviet women, Soviet education, etc. I later wound up also surveying suffrage periodicals that I accessed through the Gerritsen collection, an online database of women’s history, and also started searching online inventories of likely candidates, such as Margaret Sanger, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Crystal Eastman, Harriot Stanton Blatch, etc. In every case I found things.

I wound up consulting literally dozens of archives in the United States, as well as collections in Moscow, Amsterdam, London, and Paris. These collections ranged from personal papers to the records of the Comintern to FBI files to Quaker relief records. I also engaged with scholarship on travel writing, humanitarianism, utopia, dance and performance, race, gender and war, journalism, photography, as well as women’s history, Russian history, and the history of US-Soviet relations

When you working on this project, what surprised you the most?

The thing that surprised me the most is how right my initial impulse had been in pursuing this project. There was so much to be found, and such great material.

How would you recommend using this book in the classroom?

Because I engage with so many bodies of scholarship—but also tried to write in an accessible fashion that would emphasize the stories of the people involved, their deeper feelings, motivations, and reactions—the book can be used in a variety of ways. It is a work of US women’s history, especially considered through a transnational lens. It engages with the history of American radicalism. It presents a new angle on the Cold War and its gendered dimensions. It is a work of comparative history. It could be drawn from in courses on performance. It could be part of a course dealing with Americans abroad (I teach such a course myself). In my heart of hearts I hope people outside the academy will also be interested in the book, and that it can bridge a divide that separates books read in colleges and universities from books read by anyone else (or anyone else who reads, that is).

Related Articles

- Why did Germany lose the Battle of Stalingrad

- What were Joseph Stalin's goals as World War Two ended

- Why was the Berlin Airlift of 1948-49 successful

- What Are the Origins of Medieval Kyiv

- Why did the Allies struggle to resolve any meaningful issues at the Potsdam Conference in 1945

- Who was the first American diplomat to meet with Lenin

- How did the Carter Administration react to the Soviet Union invasion of Afghanistan in 1978

- Why did the Soviet Union create the Warsaw Pact in 1955