When did abortion become legal in the United States

While the simple answer might be 1973 with the Roe v. Wade decision, the history of abortion’s decriminalization occurred on a state-by-state basis—much like its criminalization.

In colonial America, abortion was dealt with in a manner according to English common law. Abortion was typically only frowned upon, or penalized, when it occurred after “quickening,”—when a woman felt fetal movement—because it suggested that the fetus had manifested into its own separate being. Quickening could vary from women to woman, and sometimes as late as four months. Additionally, it was only penalized because it was typically seen as some kind cover-up for improper sexual relations.

States began to draft abortion legislation in the first half of the 19th century and by 1880, every state had an abortion statute. Most of these early abortion statutes were designed to protect women from medical quacks far from the established centers of American medicine—Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, for example. These early statutes (for the most part) punished only the provider of the abortion, not the woman, and either did not apply to physicians, or did not apply if the abortion was necessary to preserve the life of the woman. Therefore, except under these special circumstances, abortion was illegal.

Nevertheless, women continued to acquire abortions—whether they were illegal or not. Until 1930, it was actually safer for women to acquire an abortion than it was for them to carry a child to term. For that reason, many women probably risked a questionable abortion. The black market’s translation into high profits compelled some physicians to specialize in the procedure, or to provide them under more generous circumstances (for example, to protect the woman’s life or health).

As abortions became black market commodities, late 19th century Americans—writers, journalists, preachers, and physicians—began to describe abortion with a moral absolutism that had never existed before.

Social Context & Legislation

This change didn’t occur within a vacuum, however. In the late 19th century, targeting abortions and abortion providers—like midwives and “irregulars”—occurred within the context of the professionalization of the medical field. Individuals like Dr. Horatio Storer attempted to legitimate themselves as professional medical men, and they did so at others’ expense. In claiming that pregnancy and childbirth were not natural events, where women and midwives could maintain authority, they argued that pregnancy and childbirth were medical conditions requiring physician intervention.

Furthermore, this new generation of physicians declared that abortion represented women’s selfishness and “antenatal infanticide in an era marked by concerns about race suicide and white women’s reproductive rates.

Throughout the 20th century, law enforcement continued to enforce local abortion statutes with limited success. Due to the nature of this criminal activity—specifically how legally ambiguous it was—it was often difficult to bring an abortion case to trial unless a woman died from the procedure. Under these conditions, it perpetuated the idea that abortions were dangerous procedures, and reformers and AMA members latched onto it with as much zeal and vigor as possible in order to advance their goals.

The Depression and advancements in medical technology changed things for women seeking abortions in the 1920s and 1930s. Sterilization of equipment, specialization, and, later, antibiotics, all worked together to decrease mortality. So while the procedures themselves became much safer, law enforcement also recognized that this created an opportunity to put patients on the stand to testify against providers of illegal abortions. Because of increased restriction in the 1940s and 1950s, more women were forced to seek out illegal abortions in substandard conditions.

Towards Legalization

The most notorious example of the dangers of illegal abortion became lionized in the cover of Ms. Magazine in 1973 when they depicted the 1964 death of Gerri Santoro. By the 1960s, the public perception of illegal abortions was that they were dirty and dangerous. American women were also acquiring illegal abortions in Mexico, which also contributed to the idea that they were illicit. Whether acquiring a back alley abortion in her hometown, two towns over, or across a national border, many women risked the unknown in order to acquire a measure of reproductive control.

The rise of these illicit abortions actually compelled some legislators in border cities to revisit their stance on abortion. Beginning in 1962, legislators in San Diego, California for example seemed to recognize there was a need to standardize abortion laws in the wake of the number of women ignoring them altogether.

There were several attempts to standardize American abortion law. The American Law Institute, for example, attempted to draft a model law for abortion in the United States that allowed for legal abortions under the conditions that most legislators approved of: in order to protect the life of the mother, if the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest, or if the fetus was likely to be deformed or ill.

Some states began to revise their abortion statutes based on the model law. In 1967, for example, California’s governor Ronald Reagan, passed the Therapeutic Abortion Act, which allowed for legal abortions when physicians believed a woman’s life or mental health would be at risk, or when District Attorneys believed the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. Other states drafted similar legislation.

Other factors contributed to easing of abortion restrictions. Specifically, a Rubella, or German measles, outbreak in the 1950s lead some physicians to believe that pregnant women who had been exposed to illness should receive abortions since exposure was likely to cause birth defects. Additionally, the Thalidomide disaster in the 1960s helped to push for legal abortion on demand. Thalidomide, a drug given to pregnant women in order to treat morning sickness or to reduce anxiety, ended up becoming one of the greatest pharmaceutical tragedies as it was soon discovered that Thalidomide actually contributed to children being born with malformed limbs. With the Thalidomide and Rubella incidents, it became apparent that existing abortion laws did not protect loving parents and nuclear families. Once the issue of nuclear families and family planning came to the fore, it became apparent that abortion could not simply be reduced to a discussion about illicit sex or immorality. Rather, it was something that even respectable families demanded, too.

In 1967, Dr. Leon Belous was arrested for referring a woman to an abortionist for an illegal abortion. As Dr. Belous took his case to the California Supreme Court, other states began to draft their own suits against their existing abortion statutes—particularly once it became obvious that Dr. Belous and his legal council intended to challenge the law, and not just his circumstances.

When the California Supreme Court ruled in People v. Belous, they recognized that California’s existing statute actually prevented physicians from performing their duties well, and it violated physicians’ due process. They also struck down the recent Therapeutic Abortion Act because they believed it was “void for vagueness.” Specifically, there was no way to determine when a woman’s life was in danger, or at risk, and there was no good standard with which to measure risk since it would violate the woman’s right to equal protection if her death had to be imminent in order to procure an abortion. When the California Supreme Court struck down their Therapeutic Abortion Act, they were unable to rephrase the statute in a way that allowed clarified it, thereby opening the door for California women to access abortion on demand.

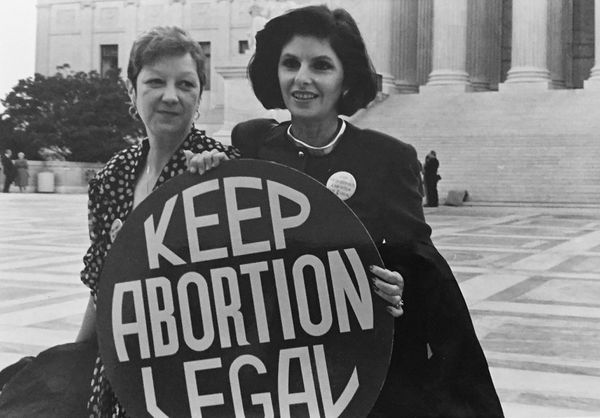

Nevertheless, it was not until Roe v. Wade in 1973 that the United States Supreme Court ultimately settled the issue. Jane Roe, a Texas resident, sought to terminate her pregnancy but Texas only allowed abortions in cases when a woman’s life was in danger. In the case, Roe’s attorneys argued that the Texas abortion statute was vague, and that it violated a woman’s constitutional rights.

In a 7-2 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a woman’s right to an abortion fell within the right to privacy as had been recognized in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) and that it was protected by the 14th Amendment.

The Roe decision gave women autonomy over their pregnancies during the first trimester, and allowed states to regulate or restrict abortions during the second and third trimester. As a result, abortion statutes in the remanding states were struck down and determined to be unconstitutional.

Bilbiography

Linda Gordon, The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America. Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 2007.

James C. Mohr, Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867-1973. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.