What was the Albany Plan of Union of 1754

The Albany Plan of Union, written by Benjamin Franklin, was a plan to place the British North American colonies under a more centralized government. On July 10, 1754, representatives from seven of the British North American colonies adopted the plan. Although never carried out, the Albany Plan was the first important proposal to conceive of the colonies as a collective whole united under one government.

Representatives of the colonial governments adopted the Albany Plan during a larger meeting known as the Albany Congress. The British Government in London had ordered the colonial governments to meet in 1754, initially because of a breakdown in negotiations between the colony of New York and the Mohawk nation, which was part of the Iroquois Confederation. More generally, imperial officials wanted a treaty between the colonies and the Iroquois that would articulate a clear colonial-Indian relations policy.

The colonial governments of Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts and New Hampshire all sent commissioners to the Congress. Although the treaty with the Iroquois was the main purpose of the Congress, the delegates also met to discuss intercolonial cooperation on other matters. With the French and Indian War looming, the need for cooperation was urgent, especially for colonies likely to come under attack or invasion.

Why was a Centralized Government Necessary?

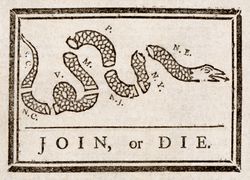

Prior to the Albany Congress, a number of intellectuals and government officials had formulated and published several tentative plans for centralizing the colonial governments of North America. Imperial officials saw the advantages of bringing the colonies under closer authority and supervision, while colonists saw the need to organize and defend common interests. One figure of emerging prominence among this group of intellectuals was Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin. Earlier, Franklin had written to friends and colleagues proposing a plan of voluntary union for the colonies. Upon hearing of the Albany Congress, his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, published the political cartoon "Join or Die," which illustrated the importance of union by comparing the colonies to pieces of a snake’s body. The Pennsylvania government appointed Franklin as a commissioner to the Congress, and on his way, Franklin wrote to several New York commissioners outlining ‘short hints towards a scheme for uniting the Northern Colonies’ by means of an act of the British Parliament.

The Albany Congress began on June 19, 1754, and the commissioners voted unanimously to discuss the possibility of union on June 24. The union committee submitted a draft of the plan on June 28, and commissioners debated aspects of it until they adopted a final version on July 10.

Although only seven colonies sent commissioners, the plan proposed the union of all the British colonies except for Georgia and Delaware. The colonial governments were to select members of a "Grand Council," while the British Government would appoint a "president General." Together, these two branches of the unified government would regulate colonial-Indian relations and also resolve territorial disputes between the colonies. Acknowledging the tendency of royal colonial governors to override colonial legislatures and pursue unpopular policies, the Albany Plan gave the Grand Council greater relative authority. The plan also allowed the new government to levy taxes for its own support.

Related Articles

- Why was the Jay Treaty so unpopular in the United States

- How did the United States react to the French Revolution

- Why did France side with the American Colonies during the American Revolution

- What caused the French and Indian War

- What was the purpose of the Committee of Secret Correspondence during the American Revolution

- Why did the Continental Congress draft and sign the Declaration of Independence

- How did the Treaty of Paris of 1783 end the American Revolution

Why did the Albany Plan Fail?

Despite the support of many colonial leaders, the plan, as formulated at Albany, did not become a reality. Colonial governments, sensing that it would curb their own authority and territorial rights, either rejected the plan or chose not to act on it at all. The British Government had already dispatched General Edward Braddock as military commander in chief along with two commissioners to handle Indian relations and believed that directives from London would suffice in the management of colonial affairs.

The Albany Plan was not conceived out of a desire to secure independence from Great Britain. Many colonial commissioners actually wished to increase imperial authority in the colonies. Its framers saw it instead as a means to reform colonial-imperial relations and to recognize that the colonies collectively shared certain common interests. However, the colonial governments’ own fears of losing power, territory, and commerce, both to other colonies and to the British Parliament, ensured the Albany Plan’s failure.

Conclusion

Despite the failure of the Albany Plan, it served as a model for future attempts at union: it attempted to establish the division between the executive and legislative branches of government while establishing a common governmental authority to deal with external relations. More importantly, it conceived of the colonies of mainland North America as a collective unit, separate not only from the mother country but also from the other British colonies in the West Indies and elsewhere.

Albany Plan of Union 1754

It is proposed that humble application be made for an act of Parliament of Great Britain, by virtue of which one general government may be formed in America, including all the said colonies, within and under which government each colony may retain its present constitution, except in the particulars wherein a change may be directed by the said act, as hereafter follows.

1. That the said general government be administered by a President-General, to be appointed and supported by the crown; and a Grand Council, to be chosen by the representatives of the people of the several Colonies met in their respective assemblies.

2. That within -- months after the passing such act, the House of Representatives that happen to be sitting within that time, or that shall especially for that purpose convened, may and shall choose members for the Grand Council, in the following proportion, that is to say,

Massachusetts Bay 7

New Hampshire 2

Connecticut 5

Rhode Island 2

New York 4

New Jersey 3

Pennsylvania 6

Maryland 4

Virginia 7

North Carolina 4

South Carolina 4

------

48

3. -- who shall meet for the first time at the city of Philadelphia, being called by the President-General as soon as conveniently may be after his appointment.

4. That there shall be a new election of the members of the Grand Council every three years; and, on the death or resignation of any member, his place should be supplied by a new choice at the next sitting of the Assembly of the Colony he represented.

5. That after the first three years, when the proportion of money arising out of each Colony to the general treasury can be known, the number of members to be chosen for each Colony shall, from time to time, in all ensuing elections, be regulated by that proportion, yet so as that the number to be chosen by any one Province be not more than seven, nor less than two.

6. That the Grand Council shall meet once in every year, and oftener if occasion require, at such time and place as they shall adjourn to at the last preceding meeting, or as they shall be called to meet at by the President-General on any emergency; he having first obtained in writing the consent of seven of the members to such call, and sent duly and timely notice to the whole.

7. That the Grand Council have power to choose their speaker; and shall neither be dissolved, prorogued, nor continued sitting longer than six weeks at one time, without their own consent or the special command of the crown.

8. That the members of the Grand Council shall be allowed for their service ten shillings sterling per diem, during their session and journey to and from the place of meeting; twenty miles to be reckoned a day's journey.

9. That the assent of the President-General be requisite to all acts of the Grand Council, and that it be his office and duty to cause them to be carried into execution.

10. That the President-General, with the advice of the Grand Council, hold or direct all Indian treaties, in which the general interest of the Colonies may be concerned; and make peace or declare war with Indian nations.

11. That they make such laws as they judge necessary for regulating all Indian trade.

12. That they make all purchases from Indians, for the crown, of lands not now within the bounds of particular Colonies, or that shall not be within their bounds when some of them are reduced to more convenient dimensions.

13. That they make new settlements on such purchases, by granting lands in the King's name, reserving a quitrent to the crown for the use of the general treasury.

14. That they make laws for regulating and governing such new settlements, till the crown shall think fit to form them into particular governments.

15. That they raise and pay soldiers and build forts for the defence of any of the Colonies, and equip vessels of force to guard the coasts and protect the trade on the ocean, lakes, or great rivers; but they shall not impress men in any Colony, without the consent of the Legislature.

16. That for these purposes they have power to make laws, and lay and levy such general duties, imposts, or taxes, as to them shall appear most equal and just (considering the ability and other circumstances of the inhabitants in the several Colonies), and such as may be collected with the least inconvenience to the people; rather discouraging luxury, than loading industry with unnecessary burdens.

17. That they may appoint a General Treasurer and Particular Treasurer in each government when necessary; and, from time to time, may order the sums in the treasuries of each government into the general treasury; or draw on them for special payments, as they find most convenient.

18. Yet no money to issue but by joint orders of the President-General and Grand Council; except where sums have been appropriated to particular purposes, and the President-General is previously empowered by an act to draw such sums.

19. That the general accounts shall be yearly settled and reported to the several Assemblies.

20. That a quorum of the Grand Council, empowered to act with the President-General, do consist of twenty-five members; among whom there shall be one or more from a majority of the Colonies.

21. That the laws made by them for the purposes aforesaid shall not be repugnant, but, as near as may be, agreeable to the laws of England, and shall be transmitted to the King in Council for approbation, as soon as may be after their passing; and if not disapproved within three years after presentation, to remain in force.

22. That, in case of the death of the President-General, the Speaker of the Grand Council for the time being shall succeed, and be vested with the same powers and authorities, to continue till the King's pleasure be known.

23. That all military commission officers, whether for land or sea service, to act under this general constitution, shall be nominated by the President-General; but the approbation of the Grand Council is to be obtained, before they receive their commissions. And all civil officers are to be nominated by the Grand Council, and to receive the President-General's approbation before they officiate.

24. But, in case of vacancy by death or removal of any officer, civil or military, under this constitution, the Governor of the Province in which such vacancy happens may appoint, till the pleasure of the President-General and Grand Council can be known.

25. That the particular military as well as civil establishments in each Colony remain in their present state, the general constitution notwithstanding; and that on sudden emergencies any Colony may defend itself, and lay the accounts of expense thence arising before the President-General and General Council, who may allow and order payment of the same, as far as they judge such accounts just and reasonable.

Republished from Office of the Historian, United States Department of State Article: Plan of Union, 1754