Why did Los Angeles adopt Cars instead of Mass Transit

By 1920, the streets of Los Angeles’s central core were some of the most congested in the United States. Pedestrians, streetcars, trains, and automobiles all competed for space on Los Angeles’s city streets, and its leaders had struggled with numerous proposed solutions to relieve traffic. How did the city of Los Angeles react to its crammed street? Why did the City ultimately decided to tie its future growth to the automobile? Los Angeles’s response to paralyzing traffic changed America’s streets because it served as a model for cities throughout the country. Instead of emphasizing mass transit and dense housing, other cities followed Los Angeles lead and promoted the automobile as the ultimate solution to congested urban cores.

Several scholars have questioned why Los Angeles rejected mass transit in favor of the automobile. In Bourgeois Utopias, Robert Fishman argues that Los Angeles deemphasized mass transit because land developers outside of the urban areas wanted to encourage growth away from transit lines. Peter Norton in “Street Walking, Jaywalking and the Invention of the Motor Age Street,” argues that automotive interests, not necessarily real estate developers, were the primary motivators for promoting the widespread adoption of cars. While Norton addresses Los Angeles specifically, his argument has much broader implications, because he believes that motorists and auto advocacy groups (motordom) fought nationally to transform America’s streets into car thoroughfares.

According to Norton, motordom sought to eliminate pedestrians, trains, and streetcars from city streets and create automobile-centric roads. In Scott L. Bottles’s Los Angeles and the Automobile, he claims that widespread dissatisfaction with the companies managing the city’s mass transit encouraged the city and citizens to turn to automobiles to solve Los Angeles’s gridlock problems. Angelinos favored cars because mass transit had failed to meet their needs. While there is some overlap in these arguments, these scholars fundamentally disagree over the spark that triggered the automotive age. While each of these arguments has merit on their own, Bottles argument is ultimately the most persuasive because he presents a compelling case that Angelinos had given up on mass transit.

Los Angeles Grows Rapidly

In 1890, Los Angeles had only 11,000 citizens and was the 187th largest city in the United States. But by 1930, it had grown to 1.2 million people in Los Angeles (2.3 million in the metropolitan area) and was the largest city in the West.[1] While Los Angeles lacked water, capital, coal, and a port in 1890 by 1930 it had “an artificial river tapped from the Sierras, a federally subsidized harbor, an oil bonanza, and block after block of skyscrapers under construction.”[2] During this time, Los Angeles was the fastest growing city in the United States, and much of this growth occurred between 1920 and 1930.

During the Roaring Twenties, approximately 1.4 million people moved to Los Angeles and Orange County.[3] People were attracted to jobs in the oil business, Hollywood, and construction. The continued expansion of Los Angeles fueled its frenetic growth. Few, if any, cities could have successfully managed this type of explosive, long-term population growth.

Unlike older American cities, Los Angeles was decentralized at birth and was never particularly accessible to pedestrians. Los Angeles was established after the introduction of the horse-drawn streetcar. This innovation permitted early residents to commute by streetcar to the central business district. Electric trolleys and trains were also fairly quickly introduced to the Los Angeles street. Early mass transit permitted Angelinos to move to even more distant suburbs early in its history. Consequentially, the central business district was not as densely populated as comparable downtowns in other American cities, and it never catered to pedestrians.

The invention of balloon frame house furthered suburban development because many Angelinos could afford to buy these modest suburban single-family homes by 1870.[4] This early pattern of decentralized growth continued over the next four decades as people immigrated to suburbs such as Pasadena, Long Beach, and Hollywood and commuted into the city center by train or streetcar. Still, even though Los Angeles was decentralized “the region had a genuine center that dominated employment, shopping, culture, and government.”[5]

The Development of Mass Transit

One of the prime beneficiaries of Los Angeles suburban growth was the owner of the Pacific Electric Company (PE), the operator of the Los Angeles electric train system, Henry E. Huntington. Before PE built new tracks in Los Angeles, Huntington purchased the land that adjoined before word leaked out that the train line would be extended through his new land. Huntington then laid out suburban housing developments on these properties. After the tracks were built, Huntington would then sell the properties. Huntington also solicited kickbacks from independent housing developers to ensure that the train would connect them to downtown. Huntington was one of the strongest advocates for downtown, and he played a major role in Los Angeles early growth patterns.

As Los Angeles’s growth began to accelerate, Angelinos became increasingly frustrated with streetcar and train companies. Like many American cities, Los Angeles depended on private rail companies for the mass transit service. The city gave the Los Angeles Rail Company (LARY) and the Pacific Electric Company (PE) monopolies, and they served as its exclusive rail providers. But as the city’s exclusive rail carriers, the companies became responsible for financing both rail service and expansion.

As immigrants poured into Los Angeles, streetcars and trains became increasingly crowded. During rush hours, both men and women were forced to stand on streetcars, and they could barely accommodate the growing number of commuters. Neither LARY nor PE could keep up with demand. The growing, decentralized layout of Los Angeles and the companies’ insistence on linking all the rail lines to the central business core complicated their efforts to expand their lines to meet customer demand.[6]

The rail companies also faced exceptionally high costs to expand their rail networks. Neither company was able to effectively expand their rail lines after 1913 because they could not “attract investment capital.” Investors were unwilling to finance the companies because they were saddled with enormous debt loads. The companies were not particularly profitable, and investors were understandably concerned that PE and LARY could not service their debts.[7] LARY’s and PE’s inability to meet passenger needs could have angered many Angelinos.

Finally, railroads had alienated Americans throughout the country during the last half of the nineteenth century because freight and passenger trains had “killed and maimed people with regularity” on America’s streets. Historian David Stowell argued that the railroads in Buffalo, New York in the 1870s had become extraordinarily unpopular among the city’s middle class. Middle-class Buffaloans had become angry with the railroads because they allied with rail workers during the “Great Strike” of 1877.[8]

While the feelings of New Yorkers may not seem relevant to Los Angeles, it is important to note, that most Angelinos were not natives and they would have carried with them their opinions of railroads from their hometowns, such as Buffalo. Injuries on trains became so frequent through the country that during the nineteenth and early twentieth century American courts fundamentally altered tort law to force railroads to improve safety standards.[9]

The Rise of the Automobile

Just as PE’s and LARY’s problems began to intensify, they were faced with a new and more flexible transportation option, the automobile. At the turn of the century, automobiles were rare and expansive, but that quickly changed. In 1908, the Ford Motor Company introduced the Model T. The Model T was not only solid and well-built, but it was also fairly cheap. Within a few years of the car’s introduction, the Model T became affordable for middle-class Americans. The Model T was especially well-suited for the growing Los Angeles sprawl. Unsurprisingly, Angelinos bought more cars per capita than anywhere else in the country. By 1915, on average there was one car for every 43.1 Americans, but in Los Angeles, there was one car for every 8.2 Angelinos. Over the next ten years, car ownership grew dramatically. In 1920, there was one car per 3.6 Angelinos and five years later there was one car for every 1.8 citizens.[10] Angelinos owned more cars per capita than any other urban area in the world.[11] Increasingly, Angelinos were turning to automobiles to navigate Southern California growing road network.

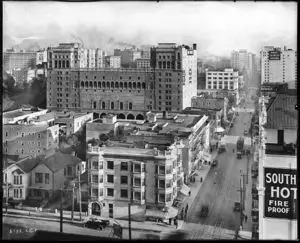

The rapid adoption of automobiles by Angelinos strained Los Angeles city streets. The city’s central business was especially taxed by the influx of cars. Cars, trains, streetcars, and pedestrians competed for space on Los Angeles city streets. While most trains stopped short of the central business district, the narrow streets could not accommodate autos, streetcars, and pedestrians. One report claimed that the congestion problem was “exceeded” by no other city.[12] Even before the introduction of the car, the central business district “suffered from streetcar congestion.”[13]

Unsurprisingly, the introduction of the car made a congested downtown even more impassable. Cars not only interfered with the smooth and timely operation of streetcars by driving on their tracks, but the streets of the central business district also became a parking lot where Angelinos stored their cars when they were at work or shopping. In 1920, the City Council even passed a law that banned parking from downtown, but City Council quickly lifted after businesses in the central core experienced sharp declines. These three forms of transportation could not coexist on Los Angeles’s narrow city streets, but automobiles had demonstrated their critical importance during the parking ban.[14]

In addition to exacerbating congestion in the central business districts, autos made the downtown streets increasingly unsafe. While streetcars were they were somewhat more predictable than cars and stayed on tracks; motorists were utterly capricious. Even more problematic was at this time that traffic was completely unregulated in Los Angeles. The mix of congestion and unsafe street conditions forced the city of Los Angeles to repeatedly address the problems of downtown congestion and develop plans to deal with the city’s progressively more treacherous streets. It is at this point in the story that Fishman’s, Norton’s and Bottles' narratives began to diverge drastically. Each of the scholars began to emphasize different facts to draw significantly different conclusions.

Los Angeles chooses a different development strategy than older cities

Robert Fishman argues that the city of Los Angeles sacrificed both its mass transit system and the central business district in the 1920s to preserve the city’s suburban ideal. He believes that as congestion intensified, Los Angeles “was forced to adopt a new strategy to preserve” its suburban model. Fishman minimized the problems PE faced and claims that PE was “still strong” in 1924 and had reached “its all-time peak in passenger miles.”[15]

In an attempt to solve the congestion crisis, Fishman claims that Los Angeles was presented with two competing proposals for addressing the city’s transportation problems. PE lobbied the city and a group of influential civic leaders to finance the construction of an above and below ground electric train system. PE’s plan was designed to preserve the downtown’s preeminence and solve the city’s traffic problems by moving the trains off the streets.

The Automobile Club of Southern California alternately advocated for a plan that fundamentally redesigned the city’s streets to create thoroughfares and speed automobile traffic.[16] The traffic plan described by Fishman is the Major Traffic Street Plan (MTSP) which was designed in part by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., Harland Bartholomew, and Charles H. Cheney. The MTSP asked the city council “to place a $5,000,000 bond issue on the ballot” to pay for “10 to 20 percent” of the plan to alter Los Angeles streets. Fishman claims that Los Angeles did not have the money to carry out both of these plans and it was forced to decide which transportation system to promote.

According to Fishman, the proponents of Los Angeles central business district faced off against rural landowners and suburban advocates. While both the mass transit and roads bond issues were put to a vote, civic leaders strongly advocated on behalf of the MTSP because it furthered the suburban ideals embodied by Los Angeles. If Los Angeles fixed its mass transit system, development would be focused around the train lines. Land prices would rise, and it would become increasingly expensive to build single-family homes along these lines, and this would complicate further expansion by the city. Los Angeles had grown dependent on single-family developers to build houses for recent arrivals.

Single-family developments were ideal for the city of Los Angeles because they could be financed cheaply and it reduced the city’s infrastructure costs. Most single-family home developments could be started with minimal financing. Developers would buy rural land from farmers and finance the construction of the subdivision’s infrastructure, including “roads, lighting, and drainage.” The developer could then sell mortgages for the first phase of homes to pay off their initial loans. After the initial set of homes was built, the builder would then finance any future home construction in the subdivision with these early mortgage sales.[17] The developers could earn large profits, and the city could cheaply expand because developers paid all of its infrastructure costs.

While retail businesses and downtown developers favored the mass transit plan, far more people benefited from the MTSP. Roads, unlike mass transit, could not only connect people to downtown, but it would also join the growing suburbs. Civic organizers railed on behalf of the MTSP and started a well-organized campaign to get the bond issues approved. While civic leaders vigorously advocated for the MTSP, a small section of the PE plan was “decisively defeated.” Fishman claims that it only then did the PE “began its rapid deterioration.”[18]

While Fishman’s conclusions are compelling, they undermined by insufficient evidence. His entire argument is based on the assumption that Angelinos wanted to preserve the suburban character of Los Angeles, but he fails to identify voices within the city that portrayed the debate over the bond issues in these terms. He has not sufficiently demonstrated that Angelinos saw the bond issue as either an affirmation or rejection of the suburban growth model. He has elevated the vote on the bond issues as a vote on the concept of suburbia. He has deemphasized the local concerns that citizens had about the election to strengthen his broader points on suburbia. The bond plan proposed by PE was expensive, and Angelinos undoubtedly realized that only benefit some suburban residents while the MTSP potentially benefited all of the cities motorists. The passage of the MTSP could be just as easily attributed to the fact that the MTSP had a broader coalition of supporters.

What Fishman successfully explains is why Los Angeles adopted a suburban model for growth. He demonstrates that suburban development was an incredibly cost-effective way for the city to quickly develop enough homes for the massive influx of people between 1870 and 1940. It is clear why city planners would prefer a growth plan that limited the capital outlays by the city of Los Angeles. Los Angeles subcontracted both the financing and the construction of its neighborhoods to private land developers.

The Rise and Power of Motordom

Norton sees a similar process to Fishman, but he argues that it was motordom, not suburban advocates which ultimately killed mass transit in favor of the motor age. Instead of examining the two bond issues voted on by the city, Norton examines the campaign waged by motordom, starting in the 1910s, against pedestrians. The roots for Los Angeles’s transition to single driver cars started much early than the process described by Fishman. As soon as cars began to use city streets, Norton explains that autos and pedestrians came into immediate conflict. Drivers and pedestrians began hurling epithets at each other. Drivers labeled pedestrians who recklessly crossed city streets as jaywalkers and walkers accused motorists of being joyriders.

While these invectives may initially appear to be innocuous, these tags highlight this earlier struggle for control of city streets. Norton argues that motordom effectively changed “prevailing conceptions of the city street” and conditioned urban residents to accept the cars takeover of their streets. By criminalizing jaywalking, motordom laid the groundwork for the takeover of the streets by cars.[19]

By the early 1920s, the Automobile Club of Southern California sought to convince city police to issue citations to jaywalkers for failing to use crosswalks. Initially, police officers simply ignored jaywalkers and failed any issue citations. The Automobile Club then engaged in a public relations campaign designed stigmatize jaywalking. Instead of asking police officers to arrest jaywalkers, they advocated whistling at jaywalkers to curb their conduct. After a year of ridiculing pedestrians, police officers were finally willing to cite jaywalkers and force pedestrians to obey traffic laws. When Los Angeles approved the MTSP, it was simply demonstrating that motordom had successfully demonized pedestrians and criminalized their unfettered use of the streets. Norton does not believe that this transformation of the city streets was inevitable, but the result of a long struggle over its purpose.[20]

Norton makes an intriguing argument that it was motordom’s long-term campaign to challenge the traditional understanding of city streets, which was ultimately decisive in laying the foundation for the motor age. While it does appear that motordom, a nebulous term at best, waged protracted battle with motorists, it is not convincing that this public relations campaign laid the groundwork for the motor age. Additionally, by 1925, most Angelinos would have been part of the loose coalition that comprised motordom. Ultimately it was not special interests, which passed to the MTSP, it the city’s motorists.

By focusing on the social reconstruction of city streets, Norton ignores dominant economic factors in favor of the automobile. Even if motordom had successfully social reconstructed the street as a place, it would have been moot if cities had not determined that cars could cheaply promote population growth. Additionally, if people had not bought automobiles then any effort by motordom to socially reconstruct the street would have quickly overturned in favor of a more economically viable paradigm. Americans ultimate acceptance of the socially reconstructed street was not based on motordom public relations campaign but on Americans, including Angelinos, willingness to invest their money in automobiles and adopt them as their primary mode of transportation.

Mass Transit Fails Angelenos

Scott Bottles promotes a substantially different explanation for why Angelinos adopted the MTSP and turned toward the automobile. He claims that Angelinos preferred the automobile to mass transit and simply expressed this preference at the ballot box. His argument is based on several pieces of evidence. Angelinos had become increasingly dissatisfied with their mass transit system. The streetcars and trains had been unable to keep up with Los Angeles’s rapid expansion after 1913. The local media and Angelinos had become extremely skeptical of the motives of both LARY and PE. They believed that the transit companies were sacrificing service in an attempt to squeeze larger profits. The city’s residents increasingly sought other transportation options, including jitneys and automobiles.

While PE and LARY had effectively scuttled jitney service in Los Angeles, they struggled to eliminate cars from downtown streets. PE and LARY did convince the city to ban parking in the central business district briefly, but the ban probably undermined support for mass transit among Angelinos. Even more problematic was that the transit companies had limited sway in the city’s growing suburbs. Unfortunately for the transit companies, the suburbs were quickly becoming new retail and commercial options. The suburbs began to represent a genuine threat to the survival of the central business district.

Angelinos also bought vast numbers of automobiles between 1910 and 1925 and by 1925 most households had access to a car. In Los Angeles, motordom would have included most of the city’s homes. The car was ideally suited for navigating and connecting Los Angeles’s various suburbs. Angelinos didn't need to preserve the urban core because jobs and shopping were beganing to migrate to the suburbs. Instead of going downtown, Angelinos in the 1920s were becoming increasingly aware that they could commute to other suburbs for work or shopping via their cars. Industrial businesses also began to relocate to the suburbs when trucks began to take over the short haul shipping business from freight trains. Trucks permitted factories to move to the inexpensive rural and suburban areas because they no longer needed to be next to a train line. The booming economy of the 1920s was fueled by industrials businesses building factories “on the periphery of the city.”[21] Factories no longer had to be accessible to trains, and the widespread acceptance of cars made it possible for even working class Angelinos to drive to work. After Angelinos expressed their preference for automobiles, city planners began to plan for an automotive city.

Bottles believe that Los Angeles’s transition to a transportation system dominated by the car was inevitable. Once Angelinos widespread dislike of the mass transit was paired with an attractive alternative, the city’s residents could reject the mass transit monopolies. The decentralized nature of Los Angeles also ensured that this transition would occur much earlier there than anywhere else in the country. The Angelinos love affair with their cars convinced them to forget about mass transit.

Bottles conclusions about why Los Angeles ultimately chose automobiles over trains are the most compelling. Bottles successfully demonstrate that Angelinos were unsatisfied with mass transit and were willing to buy cars as a potential alternative. While Bottles never explains why Angelinos bought so many cars between 1910 and 1930, it is unlikely that so many Angelinos would have invested in cars if the city mass transit system had met their growing needs. Had Angelinos been truly satisfied with LARY and PE, it is unlikely that they would have so quickly adopted such a comparably expensive alternative. Something was driving the widespread demand for automobiles.

Conclusion

Bottles explanation for why Los Angeles chose the car over mass transit does not appear to be particularly popular. Norton charges that urban transportation did not evolve in response to consumer preferences. He does not approve of the notion that people could have preferred cars to mass transit or walking. Instead, he posits that consumers were duped into accepting cars because of the public relations campaign by motordom that successfully reconstructed Americans understanding of the street. Norton’s thesis suggests that car buyers did not want to purchase their cars, but they were simply tricked into buying them. Norton completely ignores the notion that cars appealed to consumers because they “celebrate[d] individual choice.”[22]

Norton’s philosophical view of cars blinds him to the unlimited possibilities that the car presented for an early twentieth American. Norton’s argument reinforces the notion that academics have traditionally railed against “the social, intellectual and artistic poverty of America’s middle-class suburbs” because ultimately it was middle-class Americans who created the motor age.[23]

Fishman, Norton, and Bottles each seek to explain why both Americans and Angelinos turned over the future of their transportation system to the automobile. While Bottles conclusions are ultimately the most convincing, Norton and Fishman do make valuable contributions. Norton has successfully demonstrated that motorists and pedestrians came into almost immediate conflict, but his argument only suffers when attempts to expand its significance. Fishman makes an extraordinary contribution by explaining why suburbs became the dominant model for urban growth, but his account of the Los Angeles bond vote is overly conceptual. Finally, while Bottles conclusions are the most logical, they do not appear to be watertight. Hopefully, scholars will continue to examine this debate.

References

- ↑ Robert Fogelson. Bourgeois Nightmare: Suburbia, 1870-1930, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005), 147.

- ↑ Mike Davis, City of Quartz, (New York: Vintage Books, 1992), 24-25.

- ↑ Scott L. Bottles, Los Angeles and the Automobile: The Making of the Modern City (Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1987), 184.

- ↑ Bottles, 179.

- ↑ Fishman, 159-160

- ↑ Bottles, 39

- ↑ Bottles, 40

- ↑ See generally, Stowell, David. Streets, Railroads and the Great Strike of 1877 (University of Chicago Press, 1999)

- ↑ See generally Barbara Young, Welke. Recasting American Liberty: Gender, Race, Law and the Railroad Revolution, 1865-1920, (London: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

- ↑ Bottles, 92.

- ↑ Fishman, 162.

- ↑ Fishman, 162.

- ↑ Bottles, 15

- ↑ Fishman, 74-88.

- ↑ Fishman, 161, 62.

- ↑ Fishman, 164-65.

- ↑ Fishman, 164.

- ↑ Fishman, 166.

- ↑ Peter D. Norton, “Street Walking, Jaywalking and the Invention of the Motor Age Street,” Journal of Technology and Culture Vol. 48, Num. 2, (April 2007): 333-334.

- ↑ Norton: 333-334

- ↑ Bottles, 198.

- ↑ Norton, 333.

- ↑ Robert Bruegmann, Sprawl: A Compact History, (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 125.