How accurate is the movie J. Edgar

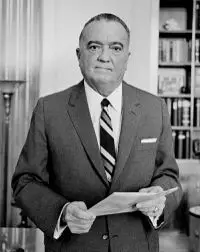

J. Edgar is a 2011 biopic of the powerful and notorious J. Edgar Hoover, former chief of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The motion picture follows the rise of Hoover (1895-1972), from a minor functionary to the head of the most powerful law-enforcement agency in America, who had great personal power. Clint Eastwood directed the movie and it was scripted by Dustin Lance Black, who won an academy award for the biopic Milk in 2008. This movie starred Leonardo Di Caprio and co-starred Armie Hammer, Naomi Watts, and Judi Dench.

The motion picture was released at the AFI Festival, and while it was a minor commercial success, it only received mixed reviews. It was not nominated for any Academy Awards even though the performances of all the actors were widely praised. The accuracy of historical biopics is often disputed, and this is also the case with J. Edgar.

Hoover and the Red Scare

The movie opens with Hoover playing an important role in the so-called Red Scare (1919). In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, there was a widespread fear of communism in America. Indeed, there were extreme left-wingers active in the USA, and the movie does accurately depict their machinations. The role of Hoover in the so-called Palmer Raids, when communists and left-wing sympathizers were arrested and deported is shown accurately (1919-1921).[1]

However, the movie shows Di Caprio’s character as masterminding this operation. In reality, Hoover was only following the directions of his mentor Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. Communism was a near obsession of Hoover, and he genuinely believed that America and its way of life were threatened by ‘Reds,’ who were under the direction of the Soviet Union. He saw communism as a disease and believed that he had to fight it constantly.[2]

The movie shows Hoover, as being inspired by a desire to save the free world from the ‘red menace’ and this is accurate. In the script, the head of the FBI was shown as being corrupted by his unflinching opposition to communism, and this was one of the reasons why he engaged in unethical and illegal behavior. It is beyond dispute that Hoover was the implacable foe of communism and socialism. The film does not capture the fact that he used the fear of communism for his purposes. He was able to manipulate the widespread fear of the ‘Reds’ to further his career and ambitions. This is something that is not raised in Eastwood’s biopic.

Hoover would routinely accuse those whom he disliked or saw as a threat to his position as a communist. He often stated that senators, political opponents, judges, civil liberties advocates, and journalists were communists so that he could impose his will on them or gain some advantage.[3] The movie tends to show Hoover as a misguided patriot, but in reality, he was a Machiavellian operator, who used the fear of communism to secure his power in the US.[4]

Hoover and the FBI

Hoover was appointed as FBI director in 1924. He is shown as an innovator and someone who was able to use the latest organizational techniques to apprehend criminals. He was indeed an organizational genius’, and this is shown in the movie when he demonstrates his new cataloging system to Helen Gandy (Naomi Watts). Eastwood also shows Hoover taking over an amateurish and shambolic organization that was not fit for purpose, and this is accurate. He overhauled and reformed the Bureau and turned it into a very professional organization.

The FBI chief did recruit only the best for his law enforcement agency, and he transformed the culture of the FBI. He was responsible for the G-Men and cultivated an aura around the Bureau to make it appear to be the leading crime-fighting agency in the country. One of the most important contributions of Hoover to law enforcement was the creation of the FBI laboratory in Quantico. This lab provided forensic analysis support to not only the Bureau but also to law enforcement agencies throughout the United States.

The most notorious head of the FBI was a true pioneer in law enforcement, and he saw the value of fingerprints, blood testing, and handwriting analysis, as essential tools in the fight against crime, and this is shown very well in Eastwood’s work. The movie also shows Hoover’s role in the battle against infamous criminals from the Depression such as Baby Face Nelson and John Dillinger, which was the case.

It was during the 1930s that the Bureau became well-known and caught the imagination of the public. Eastwood’s movie shows the notorious Lindberg case as changing the fortunes of Hoover and the FBI. In the 2011 motion picture, Hoover and his G-Men are portrayed as playing an integral role into the 1934 kidnapping of the baby son of the great aviator Charles Lindbergh (1932). It shows the main character is asked to intervene and solve the case by President Herbert Hoover and helping to apprehend the kidnapper.

In reality, the FBI played only a limited role in the case, and Hoover’s new forensic techniques did not lead to the capture of the criminal who kidnapped the Lindberg baby.[5] In one scene the central character is challenged by a Senator who claimed that he should not be the country’s top cop because he had never arrested anyone. An enraged Hoover is shown as flying into a rage and arresting some gangsters in response to the Senator’s jibes. The head of the Bureau could not arrest anyone because of a Congressional rule, and he was not that bothered by the Senator’s claims.

The FBI and wire-tapping

In the movie, Hoover revolutionized the use of wire-tapping suspects. While he did not pioneer wire-tapping, he did use it extensively and in ways that were very controversial. He first used it to tap the phones of gangsters involved in bootlegging [6]. Hoover is shown over time using it for his advantage. Hoover repeatedly authorized illegal wire-taps, not only of gangsters and criminals but also of private citizens and even prominent public figures.

The FBI chief was acutely aware that his power and authority was dependent on politicians in Washington D.C. He knew that many of them hated him and wanted him removed. Hoover used wire tapes and bugs to monitor those he believed were his foes and who was a potential threat to his position in his beloved FBI. As in the movie Hoover, did use information obtained from illegal bugging to compile files which had damaging information on many high-profile people, especially on their sex lives. Among the prominent people, he had bugged Kennedys, Martin Luther King, and Eleanor Roosevelt. Because of these files, Hoover was ‘untouchable,’ and successive President would not cross him or threaten his hold on the FBI.[7]

In the film, Hoover's illegal activity was not emphasized, and at times Clintwood’s work seemed to suggest that Hoover was acting out of a misplaced sense of duty. Moreover, as in the movie he did turn what had originally been another law enforcement agency into something else, namely a secret police force that was frequently beyond the control of the Federal Government. His position at the head of this organization made him personally very powerful and greatly feared in Washington and beyond. The movie does show the power and fear generated by Hoover. [8]

J. Edgar Hoover's sexuality

In the biopic, we see Hoover struggling with his sexuality. His mother played by the acclaimed British actress Judi Dench is portrayed as a very domineering woman who knew that her son was attracted to men. This was something that was a social taboo but was also illegal at the time. In one scene she is warning her son about the consequences of giving in to his sexual impulses when she refers to one young man who was committed to an asylum for being an alleged homosexual. There is no evidence that the relationship between Hoover and his mother was like this in real life.[9]

Later the movie shows him meeting Clyde Tolson (Armie Hammer), and the two become good friends and close colleagues. Then Tolson is shown acting as Hoover’s deputy at the FBI. The two men were very close, and they dined, vacationed together, and are buried in the same plot. Their closeness led to a lot of gossip about the exact nature of the relationship between the two men. It was rumored that they had been in a homosexual relationship since the late 1930s.

However, no one has been able to determine definitively if the relationship was a sexual one or was it merely a close friendship.[10] The movie shows Hoover and Tolson never consummating their relationship even though they were inseparable. Clintwood’s interpretation of the relationship between the two men is entirely plausible especially given the social pressures at the time.

However, there are many, especially those who worked with him in the FBI who refute any claim that J. Edgar was gay. They believe that the portrayal of Hoover as gay as slanderous and peddled by left-wingers and liberals who hated him and that the 2011 motion picture simply is repeating lies about the former head of the FBI.

Hoover and the Civil Rights Movement

Hoover was deeply alarmed by the rise of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, which sought equality for African-Americans. He suspected that many were communists and beginning in the mid-1950s he had the activities of many activists monitored and had their phones tapped and homes bugged. The FBI targeted many organizations such as the Black Panthers and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference on the orders of Hoover.[11]

Hoover slandered many leading members of the civil rights movement to successive Presidents. It seemed that the head of the Bureau did personally hate Martin Luther King. This hatred is depicted in the movie. In one scene, the viewers are shown Hoover writing an anonymous letter to the wife of Martin Luther King which gave graphic details of his extramarital affairs. With the letter is a tape with recordings of some of the civil rights leader’s infidelities. This is more or less an accurate account of what happened. It was later established that Hoover authorized the sending of the letter and the tape to Luther King’s wife and it was probably designed to prevent him from accepting the Nobel Peace Prize.

How accurate is J. Edgar

Eastwood had set himself an almost impossible objective in trying to capture a complex and contradictory figure who was one of the most powerful men in America for nearly 50 years. Many things ring true in the movie. The motion picture shows how Hoover transformed the FBI into the world’s premier law enforcement agency but also into a force that was used by him to pursue his private ambitions and his vendettas, such as his campaign against the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

The motion picture also portrays how he abused his power inspired fear in even the most powerful Americans. Eastwood managed to treat in a very sensitive manner the issue of the former head of the FBI’s sexuality. The work accurately depicts Hoover ’s rabid anti-communism.

However, the biopic depicts Hoover less corrupted by power, than by his excessive sense of patriotism, and hatred of extreme left-wing ideologies. The movie also downplays the insidious influence that he had on American public life. In general, when it comes to accuracy, the 2011 motion picture is mostly reliable and gives viewers a good overview of the life of this very controversial figure.

Further Reading

Calder, James D., and George H. Nash. The origins and development of federal crime control policy: Herbert Hoover's initiatives (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1993).

Fried, Albert, ed. McCarthyism: The great American red scare: A documentary history (Oxford University Press, USA, 1997).

Keen, Mike Forrest. Stalking the sociological imagination: J. Edgar Hoover's FBI surveillance of American sociology. No. 126 (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999).

Ellis, Mark. "J. Edgar Hoover and the “Red Summer” of 1919." Journal of American Studies 28, no. 1 (1994): 39-59.

References

- ↑ Gentry, Curt. J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (London, W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), p. 67

- ↑ Ackerman. Kenneth, Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and the Assault on Civil Liberties (New York, Carroll & Graf, 2007), p. 78, 119

- ↑ Gentry, p. 301

- ↑ Gentry, p. 318

- ↑ Gentry, P 319

- ↑ Schott, Joseph, No Left Turns: The FBI in Peace & War (New York, Praeger, 1985), p 201

- ↑ Schoot, p. 134

- ↑ Hack, Richard, Puppetmaster: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover (New York, Phoenix Books, 2007), p 113

- ↑ Hack, p 28

- ↑ Hack, p. 28

- ↑ Gentry, p 302