Difference between revisions of "How did the Versailles Treaty lead to World War Two"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

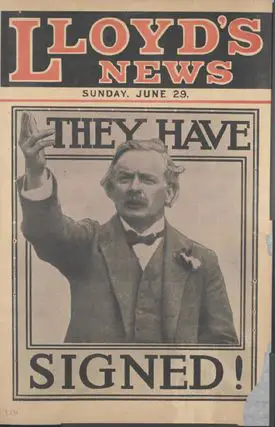

[[File:LLoyd's_News_Placard_announcing_Versailles_signing.jpg|thumbnail|275px|left|Lloyd's News reporting the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919.]]__NOTOC__ | [[File:LLoyd's_News_Placard_announcing_Versailles_signing.jpg|thumbnail|275px|left|Lloyd's News reporting the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919.]]__NOTOC__ | ||

| − | The guns fell silent on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. Over four years of incredible destruction came to a silent end. For the belligerent Central and Allied Powers the armistice brought | + | The guns fell silent on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. Over four years of incredible destruction came to a silent end. For the belligerent Central and Allied Powers the armistice brought uncertainty. The Kaiser had just been overthrown and a new alliance of Liberals and Socialists announced a democratic regime at Weimar, Germany. The other Central Powers had collapsed in disarray and revolution. Russia, out of the war in early 1918 was in the midst of a deepening Civil War. Many of the Allies were exhausted and drained. |

| − | The delegates that crafted the treaty that ended the First World War believed that they had brought a lasting peace to Europe. President Wilson believed that the war had made much of the world safe for democracy to spread. However, conflicting goals, the harsh terms of the treaty and Germany’s response to those terms would to the most destructive conflict in world history - World War Two. | + | The delegates that crafted the treaty that ended the First World War believed that they had brought a lasting peace to Europe. President Wilson believed that the war had made much of the world safe for democracy to spread. However, conflicting goals, the harsh terms of the treaty and Germany’s response to those terms would lead to the most destructive conflict in world history - World War Two. |

===Deliberations=== | ===Deliberations=== | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

[[Category:Wikis]] | [[Category:Wikis]] | ||

[[Category:German History]] [[Category:Military History]][[Category:World War Two History]] [[Category:European History]] [[Category:European History]] | [[Category:German History]] [[Category:Military History]][[Category:World War Two History]] [[Category:European History]] [[Category:European History]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Updated on September 15, 2017. | ||

| + | |||

{{Contributors}} | {{Contributors}} | ||

Revision as of 00:38, 16 September 2017

The guns fell silent on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. Over four years of incredible destruction came to a silent end. For the belligerent Central and Allied Powers the armistice brought uncertainty. The Kaiser had just been overthrown and a new alliance of Liberals and Socialists announced a democratic regime at Weimar, Germany. The other Central Powers had collapsed in disarray and revolution. Russia, out of the war in early 1918 was in the midst of a deepening Civil War. Many of the Allies were exhausted and drained.

The delegates that crafted the treaty that ended the First World War believed that they had brought a lasting peace to Europe. President Wilson believed that the war had made much of the world safe for democracy to spread. However, conflicting goals, the harsh terms of the treaty and Germany’s response to those terms would lead to the most destructive conflict in world history - World War Two.

Deliberations

The delegates of the victorious powers met in Paris to discuss the terms of the peace, followed by the treaty's signing at the former French royal palace of Versailles. Led by the "Big Four," the U.S., France, Italy, and Great Britain. Each had their own goals and vulnerabilities. While the U.S. President Wilson adhered to an idealistic view of collective responsibility and ethnic self-determination, France was driven largely by one thing: revenge. France sought to avenge its humiliating loss almost fifty years earlier in the Franco-Prussian War that resulted in a united Germany.

Generations of French policy had been consumed by this idea of revanchism and a clear opportunity finally presented itself. France demanded terms that would have completely de-industrialized and demilitarized Germany. The French floated proposals that included breaking up Germany proper and creating a client state in the industrial Rhineland. France demanded harsh reparations for the damage done to its country and Belgium during the conflict. This would materialize in over $31 billion in reparations Germany was forced to pay in the treaty terms. [1]

Shortfalls

Each of the powers represented at the treaty conference came out with some disappointments, to say the least. The British goal of stability was largely subverted by revolutions across Europe and France's demand for increasing punishment for Germany. Italy did not receive territory promised in secret deliberations during the war. The largest shortfalls appeared for France and the United States.

President Wilson's lofty goals of internationalism fell asunder in the postwar reality. The emerging League of Nations lacked the teeth needed to actually prevent an aggressive power from emerging and destroying the fragile peace. Rather than creating a series of independent democracies across Eastern Europe and the Middle East, conflict raged for years, leading to opportunities for Nazi Germany and Stalin's Russia. Furthermore, the United States never signed the Treaty of Versailles and joined the League. The U.S. Senate never ratified the Treaty, destroying Wilson's grand vision. [2]

However, it was France that had the largest impact. France's incessant desire for revenge alienated its allies and sparked radical political movements in Germany. The French understood that the country was completely drained by the war, losing almost half of its youngest adult male generation. Paris developed a decidedly defensive posture, seeking various ways to box in and humiliate Germany. France created alliances with many of the new Eastern European states, none of which would adequately function. France also created a long line of defenses along the new Franco-German border. This Maginot Line proved to be less than up to the task in 1940, despite substantial effort and investment.

German Reaction

Naturally, Germany was less than thrilled about their situation. By November 1918 nary a square mile was under Allied occupation and the Kaiser's troops still occupied a substantial part of Belgium. German propaganda had been announcing for months that their soldiers were very close to victory through much of 1918. And in many ways, they had been. The shock of defeat coupled with the harsh terms proposed carved an indelible mark in the German psyche. This led to the famous "stab in the back" theory that was so utilized by Hitler. The sight of American, British, French, and Belgian occupying the Rhineland pierced the brief calm after the fighting ended.

Furthermore, Germany's acceptance of Article 231, commonly referred to as the War Guilt Clause was for many the final straw. Germany had to accept the full responsibility for the war, including the actions of its allies. This came with a heavy price. Across its territory, various portions were carved off or plebiscites prepared. Germany lost all of its overseas colonies. France gained Alsace-Lorraine and its resources and industry lost in the Franco-Prussian War. France also occupied the Saarland, also rich in coal. Votes were held in other regions, with Denmark regaining territory lost to Prussia in the 19th Century and Poland gaining territory in both Prussia and Silesia. Perhaps most insulting was the Allied requirement that Poland have access to the sea, creating a strip that divided Germany in two. The predominately German-speaking city of Danzig became a free city. [3]

Germany's military was almost disarmed. German troops were not allowed in the Rhineland, Germany's main industrial region that bordered France. Furthermore, the Reichswehr was limited to just 100,000 soldiers. The air force was banned from having combat aircraft and the German navy lost nearly all of its surface ships and all of its submarines. Tanks were forbidden. What had been arguably the strongest army in the world was humiliated for a second time. [4]

Versailles hung heavily on the German consciousness immediately. Various political parties, especially on the emerging far right desperately campaigned against the terms. Furthermore, armed militias, often called the Stahlhelm (Steel Helmets) organized across the country burnished by Great War veterans and armaments. These militia helped lead to further undermine the unstable Weimar government, already accused by many on the right of being born on the corpse of the empire. A bizarre combination of new political party combined with militias led to emerging Communist and National Socialist conflict.

Conclusion

Rather than foster long term peace and stability, the Versailles Treaty's main goal of handling Germany instead sparked movements that would lead directly into World War II. The National Socialist, or Nazi, party would use widespread anger about Versailles with the economic collapse of the Great Depression to come to power in 1933. Six years later the world was again at war, this time far more destructive and incorporating widespread genocide. The inability for Wilson's ideals to come to widespread fruition led to further devolving situations in Eastern Europe and Asia also allowed for Soviet and Japanese expansionism. Far from preventing another war, in many ways Versailles instead caused another one.

Related DailyHistory.org Articles

References

- ↑ Roekmeke, Feldman, and Glaser, Editors. The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment after 75 Years, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. Page 90.

- ↑ Graebner, Norman and Bennett, Edward. The Versailles Treaty and Its Legacy: The Failure of the Wilsonian Vision, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011. Pages 86-87)

- ↑ Roekmeke, Reassessment, Page 45.

- ↑ Sharp, Alan. The Versailles Settlement (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, Second Edition, 2008. Page 132-133.

Updated on September 15, 2017.

Admin, TheMayor and EricLambrecht