Difference between revisions of "What was George Washington's military experience before the American Revolution"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| − | [[File:GW-painting.jpg|thumbnail|325px|George Washington and William Lee in 1780]] | + | [[File:GW-painting.jpg|thumbnail|325px|left|George Washington and William Lee in 1780]] |

The Second Continental Congress voted unanimously to put George Washington in charge of the Continental Army in 1775. Washington was only 43 years old at the time, a gentleman planter and local Virginian politician. He had not served in the military for over 20 years and his military service records was not particularly distinguished. What qualified Washington for the supreme confidence the young American rebels placed in him? | The Second Continental Congress voted unanimously to put George Washington in charge of the Continental Army in 1775. Washington was only 43 years old at the time, a gentleman planter and local Virginian politician. He had not served in the military for over 20 years and his military service records was not particularly distinguished. What qualified Washington for the supreme confidence the young American rebels placed in him? | ||

Revision as of 01:57, 5 December 2016

The Second Continental Congress voted unanimously to put George Washington in charge of the Continental Army in 1775. Washington was only 43 years old at the time, a gentleman planter and local Virginian politician. He had not served in the military for over 20 years and his military service records was not particularly distinguished. What qualified Washington for the supreme confidence the young American rebels placed in him?

Early Employment

George Washington entered the working world in his teens as an enthusiastic young surveyor. He especially enjoyed working on the frontier in western Virginia, mapping the unsettled lands controlled by his neighbor, William Fairfax. Washington's brother, Lawrence, also happened to be married to Fairfax's daughter. When George was 19, Lawrence died of tuberculosis and Fairfax took it upon himself to give George a leg up on life. [1] He urged Governor Robert Dinwiddie to appoint Washington as an adjutant in the Virginia militia, a position of varied responsibilities, mostly teaching the rowdy underclasses how to be soldiers.

At that time in 1753 the French and English were jostling for position to exploit the western lands of America beyond the Appalachian Mountains. When Dinwiddie got word that the French were building forts at the confluence of the Ohio, Allegheny, and Monongahela rivers (modern day Pittsburgh) he sent his 20-year old aide on an expedition with a letter informing the French of the British claims in the region. The French thanked Washington for coming, put him up for three days and sent him back to the Virginia capital of Williamsburg with a notice that they planned on staying. [2]

Knowing that exact answer would be forthcoming, Dinwiddie was already putting together a militia force to build a competing fort at the Forks of Ohio. The Virginia Regiment was helmed by Joshua Fry, a mapmaking partner of Thomas Jefferson's father, Peter. [3] In preparation for the mission, however, Fry was bolted from his horse and killed. Next in line to lead the troops was George Washington.

Disaster in the Wilderness

Washington and his command were soon back in southwest Pennsylvania carving roads and attempting to build a fort but the British position was overrun by a larger French force. On a dark May night in 1755 Washington's troops ambushed a small party of French soldiers, killing the leader, 35-year old Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. When word of the attack leaked out of the frontier the French claimed that Washington had opened fire on a diplomatic mission, similar to the one he had made two years earlier.[4]

The French immediately retaliated and Washington and his men were forced to huddle inside a hastily erected circular palisade they called Fort Necessity. Surrender was not long in coming and as part of the terms allowing Washington and his men to return to Virginia he was forced to take responsibility for the “assassination” of Jumonville. When word of the incident leaked from the wilderness the tensions between the French and British erupted into full warfare, known in the Americas as the French and Indian War. The British press pilloried the inexperienced Washington from across the sea. Horatio Walpole, The Right Honourable 4th Earl of Orford, was especially critical, writing " "a volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the world on fire."[5]

Washington's adventures in the western Pennsylvania wilderness were not over. The British mounted the largest military force the American colonies had ever seen under Edward Braddock, the commander-in-chief of the 13 colonies. Washington, who by this time was hoping for a career in the British army, volunteered as an aide to the major-general against the French. Braddock, however, was unschooled in wilderness fighting and his force was routed. The general was mortally wounded scarcely a mile from the ruins of the burned Fort Necessity.

Washington Takes Command

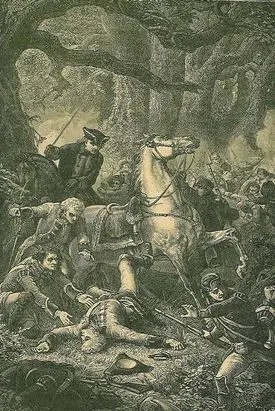

Washington had suffered a crippling attack of dysentery and was not on hand for the initial Battle of the Monongahela and he rode up to find the Braddock Expedition in disarray. Washington gallantly attempted to organize what was left of the 2,400-man force and endured “4 bullets through my coat and two Horses shot [from] under.” [6]

His actions led Governor Dinwiddie to appoint the 23-year old Washington as the colonel of the new Virginia regiment. He was responsible for recruiting 1,000 men and patrolling the Virginia frontier, which he would do for three years. In 1758, Washington resigned his commission, abandoned hopes of a permanent place in the British Army and returned to his home at Mount Vernon. He would have no further involvement with the military until 1775.

George Washington's resume at the onset of the American Revolution was: no formal military training, an inexperienced and humiliating loss in the field, a coolness of action during the retreat of the largest British army action in colonial America and the command of no more than 1,000 men. What was it then that caused John Adams to champion the appointment of Washington as head of the Continental Army?

The Crucible of a Leader

What doesn't show up on paper in the Washington war record are the intangibles. Washington had certainly demonstrated toughness, resourcefulness, and courage in the face of adversity - all of which were traits he would need in abundance during the anticipated lean years in the upcoming struggle for independence. He was a quick study of the military and political goals inherent in the Revolution. He had invaluable experience in training, drilling and disciplining troops, especially the non-military variety which would form the bulk of his Continental Army.

But most of all, George Washington was a natural leader. He was taller than his men, stronger than his men, able to summon more endurance in battle than his men, rode his horse better than his men. Washington was placed in a position of leadership at a young age and often had experienced officers many years his senior under his command. George Washington quite simply had the respect of every man he ever served with.

History tells us that the Continental Congress chose wisely. Washington lost more battles than he won and made costly blunders in the field. He also displayed consummate bravery and leadership. And no man in the American colonies could have kept the Continental Army together and fighting for nearly nine years as George Washington was able to do. And he learned those skills from his checkered military experience twenty years earlier.

References

- ↑ Chernow, Ron, Washington: A Life, Penguin Press, 2010, page 26

- ↑ Washington, George, The Journal of Major George Washington: An Account of His First Official Mission, made as Emissary from the Governor of Virginia to the Commandant of the French Forces on the Ohio, October 1753-January 1754, Dominion Books, 1959, page 13

- ↑ Britt Farrell, Casandra, “Fry-Jefferson Map of Virginia,” EncyclopediaVirginia, 2012

- ↑ Brager, Bruce L., "The Start: Jumonville's Glen and Fort Necessity,” MilitaryHistoryOnline.com, 2007

- ↑ Bradley, A.G., The Fight with France for North America, Constable Books, 1908, pg. 68

- ↑ Abbot, W.W.,The Young George Washington and His Papers, University of Virginia, 1999