The Beginning of Science-Based Religious Disbelief: Atheism and Disbelief in Victorian Britain

Contents

[hide]Introduction

For the men and women who lived through the Industrial Revolution, science was everywhere. The extent to which one embraced it was generally a matter of interplay between such factors as personal inclination, circumstance, and spare income. A substantial portion of the lower classes in Victorian Britain were apathetic to scientific theories, but there were some among these people who saw such new discoveries as proof that the Church of England and the State should revise their unobstructed grip on politics. While the working classes clung to new scientific findings as a means to enfranchise themselves, the middle and upper classes often considered such theories with a grain of salt, as they often conflicted with biblical teachings.

The fourteenth psalm of the Bible read: ‘The fool hath said in his heart, there is no God,"[1] and before modernist theo-philosophical developments in the late-eighteenth century, this phrase was taken quite literally. Essentially, being an atheist for the sake of reason or just a simple lack of belief was entirely incomprehensible in Britain before the Industrial Revolution. Atheism was seen as the result of animalistic tendencies; it was considered a conclusion reached only by the mentally unstable, as it was the ultimate form of irrationality. But, as we shall see, this would change towards the end of the eighteenth century. As many historical studies of atheism demonstrate, "intellectual" atheism changed from something unfathomable and unreasonable to something quite comprehensible.

Victorian Morality and Christianity

In nineteenth-century Britain, Christianity and morality were intimately linked concepts – a moral person must necessarily be a Christian and vice versa, so to reject religion was to identify as an immoral, base individual. A public rejection of religious belief was simply out of the question for Britain’s upper and burgeoning middle classes, as social standing was of the utmost importance during this time. (This does not mean, however, that such views were not held among members of the upper classes.) The artisan and working classes were unhindered by such societal restraints, though, and their voices loudly condemned religion as a tool used by the state to keep the lower orders subservient.

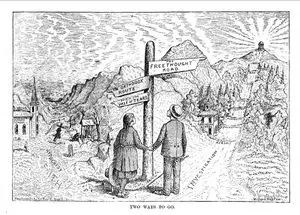

The lower classes saw that the “Holy Alliance”, which consisted of Anglican Tory aristocrats and the Church of England, must be overthrown. The notion that prevailed among the working classes was that “religion was only an instrument in the hands of the tyrant, for binding more securely the yoke of oppression, on the neck of the people.”[2] If an individual rejected morality, how was that individual to exist in a society governed by rules and laws based upon Biblical teachings? Charles Bradlaugh, one of England’s most famous nineteenth-century atheists, a Liberal MP, and the founder of the National Secular Society, sums up this notion eloquently:

"Atheism is without God. It does not assert no God. The atheist does not say that there is no God, but he says 'I know not what you mean by God. I am without the idea of God. The word God to me is a sound conveying no clear or distinct affirmation.’[3]

Such opinions, while they were widely discernible among the lower classes, were by no means commonplace during this period, in Britain, or anywhere else in Europe. In this article, I will examine a few different viewpoints on irreligion in the nineteenth century, and explore how, where, and why such digressions from the “accepted” theological teachings existed.

The Historical Record

Studying atheism can be very frustrating for the historian – all those who did not believe in a state’s religion (in Britain’s case this was Anglicanism) were generally considered atheists, while, for the most part, these people were simply deists (deists believe that God created the universe, but reject the idea that God intervenes in everyday life), non-conformists, and believers of other various Christian or Abrahamic religions. Atheism was seen not as a rejection of religious belief, but rather as a serious crime in that non-Anglican beliefs were considered a rejection of morality and national identity. In the nineteenth century, atheism was a theological, moral, and legal problem – such beliefs were not confined to the realm of personal philosophy.

Another prevalent oversight of historical studies of atheism is that scholars automatically assume that irreligion was only a working-class phenomenon, as the British working classes were those who had the most grievances against the government. The problem with associating atheism almost exclusively with the lower orders is that the historiography on the subject cites moral philosophy and social theories published by men of primarily upper-class standing as the primary catalyst of atheistic ideologies. Most historians believe that atheistic thought originated among the higher orders, and subsequently made its way down into working-class periodicals and newspapers via a "trickle-down" effect. This, however, is far from true. While Victorian “gentlemen” might’ve fashioned their private beliefs concerning Christianity’s relevance after reading such social theorists/philosophers as Thomas Paine or David Hume, the literate working classes were forming their own religious philosophies based upon entirely different sources (i.e. penny periodicals).

Over the course of the nineteenth century, improvements in printing techniques and reductions on printing taxes had drastically lowered the cost of producing everything from daily newspapers to full-length books. Literacy rates were also going up. These factors paved the way for daily, weekly, and monthly periodicals aimed directly at the working classes, many of which were vehemently anti-establishment. In 1842, Charles Southwell, William Chilton, and John Field created the first avowedly atheist periodical in England, entitled the Oracle of Reason. Many similar periodicals followed, ranging from those who used science to rebuff religion, to those who manipulated working-class politics in ways that necessitated a rejection of religion.

Science and Religious Belief

While much of the modern historiography on Victorian social history holds that religion and scientific doctrines were not mutually exclusive belief systems, this was not necessarily true in the nineteenth century, nor is it entirely true now. Many Victorian atheists used new scientific findings, especially evolutionary theories, as props against theistic belief. The nineteenth century was a time when new scientific knowledge came about almost monthly and was disseminated among the public like never before. Periodicals made this information available to almost all facets of society, including the artisan and working classes.

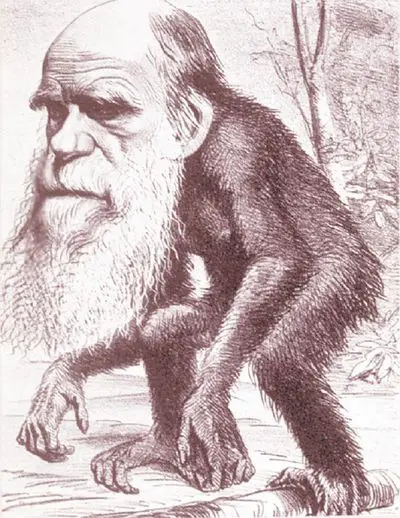

In 1821, Richard Carlile, a notorious radical political agitator, published a treatise entitled An Address to Men of Science in which he encouraged gentlemen naturalists to put forth their scientific theories without regard for these theories’ potential conflicts with the doctrines of the Church of England.[4] Evolutionary theories, which were gaining in popularity in the early-nineteenth century, were becoming mainstream discourse not only among not only the upper classes, but also among the literate working classes. When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, theories of the transmutation (evolution) of species had been in the public sphere for quite some time. Such biological treatises presented the greatest threat to the Anglican (Church of England) belief system, as they directly conflicted with biblical accounts of creation. According to the Christian bible, God had painstakingly created each species on Earth, from the smallest insect to the largest mammal; but as evolutionary theories began to gain more headway, this notion seemed more and more improbable.

Politics and Religious Belief

When we analyze the reasons for the support of Victorian scientific theories among the working classes, we find that the underlying motivation for most new patronage of new naturalistic/scientific theories was often political. With the technical innovations of the Industrial Revolution having brought about an overabundance of cheap and unskilled labor, the attitude of the working classes toward the State and those of higher social standing was becoming more and more agitated. To the working men and women, commenting on the ins and outs of new scientific theories was not as obligatory as recognizing the massive potential these theories had to undermine Church authority. Through careful manipulation in the penny periodicals, the boundaries of science became more and more ambiguous, as scientific theories became less about the study of the natural world, and more about how they could be used as paradigms of opposition to the establishment.

Many among the working classes blamed poverty and class stagnancy on an unaccountable executive that oppressed them through taxation, and rubbed it in by denying them political representation (the vote). The gradual debasement of craftsmanship coupled with an inability to participate in their government was the “experience which underlay the political radicalization of the artisans”.[5] So, it should not come as a surprise that this group of discontented and ambitious men and (some) women did not normally engage in scientific studies simply for intellectual cultivation. Their sciences were “angry, working sciences, sometimes half articulated, often half taken for granted”.[6]

Conclusion

We have now seen that the ambiguities of nineteenth-century scientific theories rendered them easily appropriated by a wide variety of groups. Yet, to the men who conceived these theories, any interpretation of them was generally seen as unnecessary; to them, scientific study had advanced far enough to be accepted as universal truth. Working-class radicals were engaged in their own study of the natural world – their environment was as full of struggle as anything Darwin had envisioned, and the method by which they could overcome this struggle was the working-class version of science.

Irreligious groups have stood in an ambiguous and complex place among historians, both in religious and cultural studies. Atheism, despite the implications of its prefix, was not the antithesis of religion, but, nor was it a substitute. Yet atheism deserves recognition as a religion in the sense that it was the product of a search for truth, and an attempt to understand man’s place and purpose in the universe. To define atheism as a philosophical concept does not prove nearly as difficult as ascertaining its presence historically. The historiography of atheism is often considered a “hidden” history – meaning that there likely did exist a rich dialogue that concerned atheism in the last few hundred years. Unfortunately, though, we have no way of discovering such documents, as such beliefs were illegal, and therefore, not widely professed. This was especially so in Great Britain, where the Church and State have been intimately linked since the seventeenth century. And while that relationship is currently changing to accommodate the beliefs of a more secular society in the 21st century, the echoes of such policies continue to affect day-to-day affairs in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.- Jump up ↑ Psalm 14:1-7 (KJV).

- Jump up ↑ Edward Royle, The Infidel Tradition from Paine to Bradlaugh (London: Macmillan, 1976), 94.

- Jump up ↑ Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant, The Freethinker’s Textbook." (London: Freethought Pub. Co., 1876), 144.

- Jump up ↑ Richard Carlile, An Address to Men of Science: Calling Upon Them to Stand Forward and Vindicate the Truth from the Foul Grasp and Persecution of Superstition (R. Carlile, 1821).

- Jump up ↑ E.P. Thompson: The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Vintage Books, 1966). 262.

- Jump up ↑ Adrian Desmond, The Politics of Evolution (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989), 4.