Why Did American Colonists Become United Against England

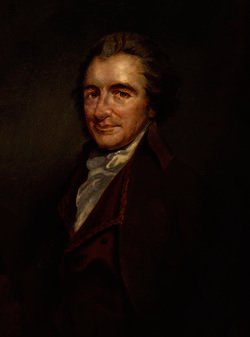

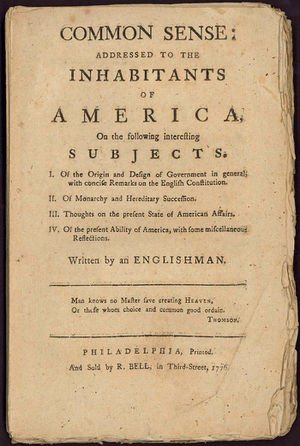

Colonial Americans enjoyed relative independence from England until 1763, which marked the cessation of the Seven Years’ War. Prior to that time, the British government had paid little attention to the domestic affairs conducted by their American colonists. The war was costly; however, and England deemed it appropriate that American colonies contribute to the war debt and the costs associated with stationing British troops on American soil. The British government assessed taxes on the colonies yet denied colonists the right to Parliamentary representation in the House of Commons. As a result, Americans saw themselves as being subordinates to the Crown rather than as equal members of the British Empire, thus prompting the colonists to rebel against their mother country in the name of liberty. Parliament’s actions fostered a sense of rebellion amongst the inhabitants of America, while Thomas Paine unleashed a patriotic fervor throughout the colonies that solidified a nation.

Englishmen and Americans alike were filled with British pride following the successful conclusion of the Seven Years’ War. Americans, who were separated both geographically and governmentally from England, felt a renewed sense of kinship with their British brethren. This attitude began to change when King George III issued the Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited colonial expansion west of the Appalachian Mountains. Not accustomed to Crown intervention pertaining to domestic affairs, agitation began to stir amongst rebellious colonists.

Taxes

When Parliament passed the Sugar Act of 1764, the British pride felt by Americans quickly began to wane.[1]Although this act did decrease the taxes paid by colonists on imported molasses, the long established practice of smuggling goods in and out of the country, which violated the Navigation Acts of 1651, was no longer feasible.[2]The Sugar Act, along with the simultaneously enacted Revenue Act, was detrimental to coastal merchants. The Revenue Act mandated that wools, hides, and other items that were not previously subjected to the Navigation Acts, were required to pass through England rather than being shipped directly from America to their destinations. This was another yet attempt by King George to attain money from the colonies in order to reduce England’s war debt. American citizens, already feeling the pangs of post war recession, were feeling their economic security threatened.

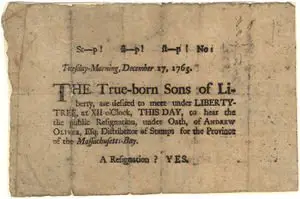

The disenchantment with Britain, which was slowly simmering, reached a fevered pitch in 1765 with the passage of the Stamp Act; the first direct tax Parliament had levied on the colonies. Whereas all other duties had been paid through trade regulations, this law constituted direct governmental intervention upon a people who had no representation in Parliament. Colonists were of the mind to be dutiful English citizens when they were treated as such. The Stamp Act, which required a stamp purchased through British authorities to be affixed to all printed materials, threatened both the finances and liberties of colonists.[3]While providing the first major split between England and America, the Stamp Act concurrently began to unite the colonies as a nation.

Signs of Unification

Americans surprised London merchants by boycotting English goods while the Stamp Act was in effect. Colonists banded together, with the urging of such groups as the Sons of Liberty, and posted numerous broadsides and conducted impromptu meetings in the streets to heighten their fellow citizens’ awareness of the oppressive actions being taken by Parliament. Groups such as these began to appear throughout the colonies and politics began to consume the thoughts and conversations not only of colonial leaders, but of average citizens as well. According to historian Eric Foner, “Parliament had inadvertently united America.”[4]Rather than seeing themselves as separate entities, the colonies were cooperating rather competing with one another. Colonial unification became more formal in October 1765 when the Stamp Act Congress met in New York. Colonial leaders convened and formally advocated the boycott of British goods. The boycott posed a formidable economic threat to London merchants, who successfully persuaded Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act just one year after its issuance.

Boston

The growing trend of unification among colonists and dissention towards the British came to a violent climax on March 5, 1770 in an event known as the Boston Massacre. A confrontation between colonists and British soldiers on the streets of Boston escalated to violence resulting in the death of five Bostonians. The details of the event were (and still are) blurred and biased, yet Massachusetts silversmith Paul Revere created an etching that depicted British soldiers executing unarmed Bostonians. This type of propaganda escalated anti-British sentiment, which in turn bolstered colonial pride and the determination to gain and hold liberty. The quest for liberty and equal justice was exemplified by the action of John Adams when he chose to defend the British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre. Adams held that in order to fight for justice and equality, all were due a fair trial, including the British soldiers. His loyalty to the Patriot cause was well known, thus affording him the ability to emerge from this endeavor unscathed and with his esteemed reputation intact.

With the new taxes imposed and continued Crown intervention, Americans became more ardent in their resolve that they would not become enslaved to a distant government. Liberty was on the minds of patriots while the idea of independence from the British Empire crept into the discussions of colonial leaders. The climactic event which propelled the final split with England came on December 16, 1773 when certain colonists engaged in what became to be known as the Boston Tea Party. Sam Adams supposedly instigated the act of disposing of a shipment of British tea into Boston Harbor; which cost the Crown over ten thousand pounds in revenue. The Tea Act issued earlier in the year agitated rebellious colonists to the point of destructive and violent action.

The subsequent reaction from London was to further oppress the colonists through a stringent new set of laws Americans called the Intolerable Acts. King George’s wrath was aimed at New England, thus he closed the port of Boston until compensation was made for the lost tea revenue. Through these acts, town meetings in Massachusetts were stifled; the British government appointed council members in New England and lodged soldiers in private homes.[5]Outrage swept not only through New England but throughout all American colonies.

Massachusetts delegates met in September 1774 and concluded that New England taxes would be withheld, preparations for war would be made, and obedience to England would be denied. These resolutions were known as the Suffolk Resolves. To further reinforce solidarity, leaders of all the colonies, except those from Georgia, met in Philadelphia as the First Continental Congress. The goal of the convention was to coordinate a unified response to the Intolerable Acts[6] This historic meeting did more than coordinate colonial efforts; the concrete unification of a nation transpired. Virginia orator Patrick Henry best described the attitude of the nation when he proclaimed, “‘I am not a Virginian, but an American.’”[7] Unwittingly, England had united her once subordinate colonists into a formidable adversary.

Common Sense

In an ironic twist, colonists who were once filled with British pride were now consumed with American patriotism. When Americans realized they were never to be thought of as equals to Englishmen, they resolved to find that sense of equality among themselves; while concurrently denying such liberties to those who were deemed inferior. Such men as John and Samuel Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry courageously paved the path to freedom for white men in the colonies. Arguably, the man most instrumental in the movement towards independence, and perhaps the forgotten Founding Father, was Thomas Paine.