Were Members of the Underground Railroad Criminals

“But I do earnestly desire to arouse the women of the North to a realizing sense of the condition of two millions of women at the South, still in bondage, suffering what I have suffered, and most of them far worse.”[1]These are the words of Harriet Jacobs, who lived in a state of chattel slavery for twenty-seven years. After her courageous escape to the North, through various undertakings, she was able to write her personal history. In the preface to her story——and throughout the text——she appeals to women of the North as mothers to act on behalf of the enslaved mothers of the South. Through personal experience, she understood the level of degradation suffered by a slave and that the right Americans had to trade in human beings was a bad law.

As millions of people were being held against their will, the slave owners were reaping the benefits of free labor, while citizens elsewhere held varying opinions. The more noble citizens in Antebellum America acted as abolitionists, often placing themselves and their families in great peril. Why did ordinary men and women risk their very lives by breaking the law to help strangers? They acted as they did for the greater principle of liberty and justice. Aiding and directing fugitive slaves toward liberty was utilitarian justice and did no harm to slave owners as the legalization of slavery was, in itself, a “bad law,” thus making it the antithesis of a moral right.

Fugitive Slave Laws in America

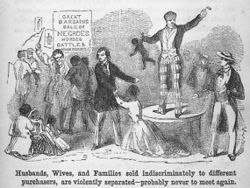

America was built on the backs of slaves. On the eve of the Civil War, these human beings were second only to land as the most valuable commodity in the southern states. Slave owners, therefore, felt compelled to initiate legislation to protect their valuable, human assets. Although the United States Constitution protected slavery under Article IV, and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 allowed slave owners to cross state lines to retrieve their property, a growing number of abolitionist groups in the North were harboring runaway slaves in order to protect them from the pursuit of their masters. As tensions grew between the two regions of the country regarding the South’s peculiar institution, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered a decision in 1842 finding, “the slaveholder’s right to his property overrode any contrary state legislation.”[2]The Court, however, continued in its opinion that enforcing the Constitutional clause relating to slavery was the onus of the federal government and that “states need not cooperate in any way.”[3] That being the case, large plantation owners of the South pressured their Democratic representatives in congress to pass the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which mandated “all good citizens” to report their knowledge of fugitive slaves to authorities.

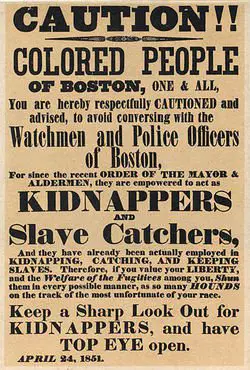

Southerners viewed the Act as a means of frightening the burgeoning network of abolitionists who comprised, in part, the Underground Railroad (UGRR). Slaveholders described the UGRR as a “Yankee network of lawbreakers who stole thousands of slaves each year.”[4]Criminal punishment of monetary fines and prison sentences were the tools of intimidation employed by the authors of the Act; unauthorized threats came from slave owners directly. Staunch abolitionists, such as Wendell Phillips, vehemently opposed and blatantly disregarded the federal law scarcely one month after its passage. Phillips incited his fellow Bostonians into protecting, at all costs, a pair of fugitives who had enjoyed two years of freedom in Boston before the passage of the Act. Bostonians turned out in droves and soon sent the slave hunters back to the South, empty handed. A newspaper in Boston declared, “Massachusetts Safe Yet! The Higher Law Still Respected,” while a paper in Georgia deemed Boston to be a “black speck on the map.”[5]Although a victory for the abolitionist cause, not even the great city of Boston was able to continue fighting the growing number of slave catchers infiltrating the Bay State. Going forward from 1850, the UGRR and all other escape networks had to go further north into Canada; the U.S. was no longer able to assure life and liberty.