How did the United States acquire Florida

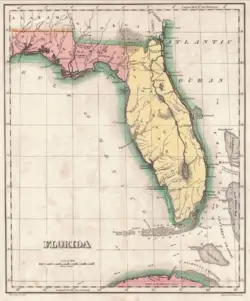

The colonies of East Florida and West Florida remained loyal to the British during American independence. Still, by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, they returned to Spanish control. Spain's control over Florida was precarious. Over time, after Americans began to move into the territory, it became clear that Spain would not maintain authority over the region. Ultimately, Florida was handed over to the United States under the terms of the Onís-Adams Treaty of 1819.

Why did Americans move into Florida during the American Revolution?

After 1783, American immigrants moved into West Florida. In 1810, these American settlers in West Florida rebelled, declaring independence from Spain. President James Madison and Congress used the incident to claim the region, knowing that Napoleon’s invasion of Spain seriously weakened the Spanish government. The United States asserted that the portion of West Florida from the Mississippi to the Perdido rivers was part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Negotiations over Florida began in earnest with Don Luis de Onís to Washington in 1815 to meet Secretary of State James Monroe. The issue was not resolved until Monroe was president and John Quincy Adams his Secretary of State.

Why John Qunicy Adams expand into Florida?

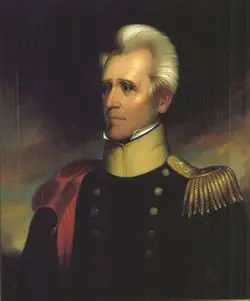

While the United States had already annexed West Florida, no one recognized the American claim. Still, Spain was incredibly weak and had little control over its territory. Spain's weakness gave the United States a unique opportunity to seize Florida. In addition to Spain's troubles, the Secretary of War, Henry Calhoun, had dispatched Andrew Jackson to quell Seminole raids into Western Florida and Georgia. This military action quickly became the First Seminole War. As part of this action, Jackson moved into Spanish territory without consent.[1]

U.S.-Spanish relations were extremely strained because it justifiably believed that the American support for Spanish-American colonies' independence struggles was an overt attempt to seize Florida. The situation became even more critical when General Andrew Jackson was thrust into Florida resulted in the Spanish forts' seizure at Pensacola and St. Marks in 1818. Additionally, he drove further into Florida when he sought to kill Seminoles and escaped slaves, who he viewed as a threat to Georgia. Jackson even executed two British citizens on charges of inciting the Indians and runaways.

Why did Spain give Florida to the United States?

Monroe’s government seriously considered denouncing Jackson’s actions, but Adams defended Jackson, citing the necessity to restrain the Indians and escaped slaves since the Spanish failed to do so. Adams also sensed that Jackson’s Seminole campaign was popular with Americans, strengthening his diplomatic hand with Spain. Adams used Jackson’s military action to present Spain with a demand to either control the inhabitants of East Florida or cede it to the United States. Minister Onís, due to France's takeover by Napoleon, left Spain with few reasonable options. Florida was not able or particularly interested in maintaining its presence in Florida.

What was the Onís-Adams Treaty of 1819?

Minister Onís and Secretary Adams reached an agreement whereby Spain ceded East Florida to the United States and renounced all claims to West Florida. Spain received no compensation, but the United States agreed to assume liability for $5 million in damage done by American citizens who rebelled against Spain. Under the Onís-Adams Treaty of 1819 (also called the Transcontinental Treaty and ratified in 1821), the United States and Spain defined the Louisiana Purchase's western limits, and Spain surrendered its claims to the Pacific Northwest. In return, the United States recognized Spanish sovereignty over Texas. While Spain's rights to Texas were recognized, that situation changed extraordinarily fast when Mexico received its sovereignty on September 27, 1821.

- Republished from Office of the Historian, United States Department of State

- Article: Acquisition of Florida: Treaty of Adams-Onis (1819) and Transcontinental Treaty (1821)

References

- ↑ Alan Brinkley, American History, 11th edition (McGraw Hill, 2003), p. 226.