Why Did Helen Keller Become a Socialist

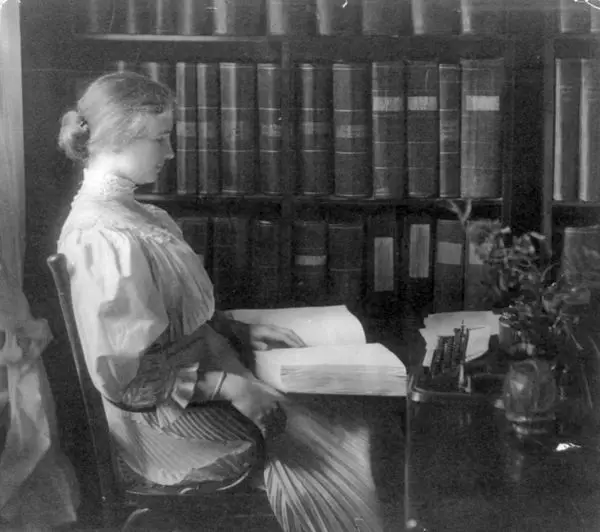

Helen Keller (1880–1967) is best known for her triumph over blindness, deafness, and muteness. Rescued from the isolation of her afflictions as a young girl by the Perkins Institute for the Blind teacher Anne Sullivan, Keller learned to understand a basic form of sign language and learned to “feel” and imitate the sound of the human voice. With a world of comprehension and communication opened to her, Keller excelled, graduating cum laude from Radcliffe College, eventually writing books about her life and education under Sullivan, appearing in motion pictures to demonstrate her communication methods, and campaigning for the deaf and blind around the world.

For all of this fame, however, not many know that Keller was also a prominent figure in the American socialist movement: a champion of the working class against industrial oppression, a consistent foe of militarism and imperialism, and a crusader for a better society.

Out of the Darkness and Silence

Keller was born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama, to Arthur Keller and Kate Adams Keller. Her first nineteen months were unremarkable, until she contracted a brief unidentifiable illness, characterized by a high fever that left her deaf and blind, and with only snippet memories of the broad fields, wide sky, and tall trees of Tuscumbia. Physicians declared the Kellers’ daughter a hopeless case, suggesting that she be permanently institutionalized, but the devoted parents kept searching for ways to lift her from dark silence. They discovered the Perkins Institute, a training school for the blind in Boston, and inquired about a teacher for Helen. After some discussion, the headmaster sent Anne Sullivan to Tuscumbia, where she was met with an out-of-control, frustrated, and depressed six-year-old child—yet one with a hidden radiance and an eagerness which Sullivan was anxious to tap.

The outstanding results of the relationship between student and teacher were made famous by the 1962 film The Miracle Worker, which profiled Sullivan’s ability to connect with Keller and eventually provide her with the tools to learn and communicate by finger spelling words in the palm of her hand.[1] Keller’s quick mastery of that method launched her to organized classroom study at the Perkins Institute, where she learned to read Braille and to communicate more freely via the manual alphabet. Her vocal speaking practice was begun at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf in Boston. Although her speech would never be perfectly clear (something she regretted all her life), by the age of ten, she could at least make herself heard, and excitedly reported to Sullivan, “I am not dumb now.” [2]

Birth of a Leftist Consciousness

The experience of isolation, the realization that mutual understanding and cooperation can overcome silence and darkness, and the sheer determination to be heard—all of Keller’s literal experiences—were easily translated into a push to overcome the figurative isolation, silence, and darkness that many marginalized groups were experiencing in American society during the 1910s, the period just after Keller graduated from Radcliffe. By this time, she was living with Sullivan and her new husband, John Macy, a young Harvard University instructor and a social critic. Macy was angry about the inequality he believed was caused by the machinations of the U.S. capitalist system. He was also sympathetic to the oppressive circumstances under which workers labored and the squalid conditions in which they and their families lived.

Living in the same household as the Macys, Helen would certainly have been exposed to Macy’s disgust and his sympathetic ideals, but it is clear that by the 1910s she was independently arriving at similar understandings and conclusions. During her time at the Perkins Institute and the Horace Mann School she had walked with Sullivan through the slums of Boston and had been overwhelmed by the stench of the hideous, sunless tenements, overcrowded with working-class families living on the edge of starvation. Her burgeoning interest in the causes of the blind raised her awareness of the commonness of the affliction among the working poor, caused by industrial accidents among men, women, and children in mines, mills, and factories. She discovered that too many cases of blindness were caused by “wrong industrial conditions and the greed of employers. But the social evil [also] contributed its share. I have found that poverty drove women to the life of shame [prostitution] that ended in blindness [a complication of sexually transmitted diseases].”[3]

The connection between blindness, industrial dangers, and women’s issues awakened Keller’s left-leaning social consciousness. Her acceptance of socialism, specifically, came after she read H. G. Well’s New World for Old, which had been published just a couple years prior. In the book, Wells describes in detail the working-class children who “grow up, through a darkened, joyless childhood into a gray, perplexing, hopeless world that beats them down at last, after servility, after toil…to despair and death.” [4] He ends by asking and answering a basic question: “What freedom is there today for the vast majority of mankind? . . . They are free to do nothing but work for a bare subsistence all their lives; they may not go freely about the earth.”[5]

These inequalities and restrictions, Wells argued, could be solved by socialism, which “lights up certain once-hopeless evils in human affairs and shows the path by which escape is possible.”[6] The ideology would also “end that old [male] predominance [over female] altogether. The woman must be as important and responsible a citizen in the state as the man. She must cease to be in any sense or degree private property.”[7]

This made sense to Keller, and she set out to read all she could on socialism, subscribing to German socialist periodicals printed in Braille, and she asked a friend to visit three times per week to finger spell entire articles from the International Socialist Review and the National Socialist, and other readings (such as works by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Kautsky) from the Macys’ home library. “It is no easy and rapid thing to absorb through one’s fingers a book of 50,000 words on economics. But it is a pleasure, and one which I shall enjoy repeatedly until I have made myself acquainted with all the classic socialist authors.”[8] She finished her foundational preparation and officially joined the Socialist party, a fact made public in 1912, but she was a bit vexed about what her disabilities would allow her to do for the movement. Recalling her reading of New World for Old, however, she renewed her sense of the role she could play in helping realize socialism’s triumph over the political, economic, and social ills of the day. Wells had written that “an immense amount of intellectual work remains to be done for socialism. . . . The battle for socialism is to be fought not simply at the polls and in the market place but at the writing desk and in the study.”[9]

Keller decided to use her Braille machine and her “voice” for the cause, even though she could not participate in the day-to-day activities of the movement. She spoke and wrote frequently on behalf of workers on strike but was simultaneously “heartily disgusted” with the conservative policies of American Federation of Labor (AFL) leadership.1[10] The AFL emphasized organizing mainly skilled white male workers in craft unions; Keller’s reading and thinking led her to admire, instead, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which advocated industrial unions for all workers regardless of skill, sex, or race. She was particularly attracted to the group’s militant tactics, in her mind an innovative way to push for a new society. Keller was also on the side of the militant drive for woman suffrage—including the use of protests, boycotts, and hunger strikes.

By Choice or by Coercion?

Several publications of the period wrote about Keller’s adoption of the socialist cause with pity, as if she was the innocent victim of Macy’s and Sullivan’s ideological indoctrination. Common Cause, for one, worried that “both Mr. and Mrs. Macy are enthusiastic Marxist propagandists, and it is scarcely surprising that Miss Keller, depending upon this lifelong friend for her most intimate knowledge of life, should have imbibed such opinions.”[11]

Helen responded to the concern, pointing out the reports’ hypocritical sympathy in touting her triumph over isolating disabilities while suggesting that she, a poor blind and deaf girl, was being exploited. “So long as I confine my activities to social service and the blind, the newspapers compliment me extravagantly, calling me ‘archpriest of the sightless’ or ‘a modern miracle.’ But when I discuss poverty as the result of wrong economics or advocate that all human beings should have leisure and comfort, the decencies and refinements of life, I must, indeed, be deaf, dumb, and blind.”[12] She retold the story of her discovery of socialist ideals and the hard work she had put into familiarizing herself with what socialism could offer to the United States: “I can read all the Socialist books I have time for in English, German, and French.”[13] She concluded by encouraging each editor of the publications that simultaneously praised and pitied her to read the same items. “He might be a wiser man and make a better newspaper.”[14]

The Blossomed Socialist

Anyone who thought that Keller had been coerced into following socialist tenets should have been convinced otherwise by her activities through the 1910s. During that time she was a crusading socialist, speaking in support of women’s suffrage and birth control, in opposition to World War I, and on behalf of the labor movement—in settings as intimate as New York’s Astor Hotel and arenas as large as Madison Square Garden. Regardless of the venue in which it was delivered, the message always pointed to the promise of a world without poverty or war. “The seeds of the socialist movement are being scattered far and wide, and the power does not exist in the world which can prevent their germination.”[15]

In 1921, after more than ten years of public activism for the socialist cause, Helen decided that her humanitarian efforts should be devoted primarily to raising funds for the American Foundation for the Blind. Her activities for the socialist movement decreased but did not end, and her private letters reveal that her faith remained strong. “There abides with me a gratifying sense that casting my lot with the workers, even if only in dreams and sentiments, has given me symmetry and dignity to my womanhood and enabled me to face unashamed the spiritual challenge which is quite as searchingly fiery as the economic ordeal.”[16]

Although Keller vocally and publicly supported the socialist movement for only a decade, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) maintained a detailed investigative file on her until her death in 1967. Few may now be aware of her socialist activism, thinking of Keller only as a woman who fought tremendous disabilities to become a great humanitarian. Ironically, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover focused on only that socialist activism, dismissing all of Keller’s remarkable personal achievements with a one-line summary of the woman his bureau perceived as a threat: Keller was “a writer on radical subjects.”[17]

Related DailyHistory.org Articles

References

- ↑ The Miracle Worker, dir. Arthur Penn (Playfilm Productions, 1962).

- ↑ Hattie Schlossberg on Helen Keller's speech patterns, interview, New York Call, May 4, 1913.

- ↑ Helen Keller, "Social Causes of Blindness," ibid., Feb. 15, 1911.

- ↑ H. G. Wells, New World for Old (New York: Macmillan, 1909), 26.

- ↑ Ibid., 28.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 30.

- ↑ Helen Keller, "How I Became a Socialist," New York Call,Nov. 3, 1912.

- ↑ Wells, New World for Old, 52.

- ↑ Helen Keller, "To the Strikers at Little Falls, N.Y.," Solidarity, Nov. 21, 1912.

- ↑ "The Politics of Helen Keller," Common Cause, Sept. 8, 1911.

- ↑ Helen Keller, "To the Editor of the New York Evening Sun," New York Sun, June 8, 1913, reprinted in New York Call, June 11, 1913.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Helen Keller, "A New Light Is Coming," New York Call, July 8, 1913.

- ↑ Helen Keller, "onward, Comrades," address to the Rand School New Year's Eve Ball, Dec. 31, 1920, reprinted in New York Call, Jan. 30, 1921.

- ↑ Jack Anderson, "FBI Kept Dossier on Helen Keller," New York Post, Feb. 19, 1979.

Admin, Cyaudes and EricLambrecht