Who was Theseus the great Athenian king and hero?

Athens was perhaps the most important city in the entire history of Classical Civilization. Many scholars regard it as a seminal influence on the development of Western culture. However, few people remember the mythical founder of Athens, Theseus. Probably best known for killing the half-bull and half man the Minotaur, this hero was so much more. He was the greatest Athenian king who united them into a powerful city and defeated the enemies of civilization. His cycle of myths offers unique insights into Athens and its history.

Life and early adventures of Theseus

In the cycle of myths based on the adventures of Theseus, he was born in Attica. His father was King Aegeus of Athens, but his birth father may have been the God Poseidon. The future hero’s mother was Aethera, a princess from Troezen in the Peloponnese. Here Theseus spent his youth until he came of age and went to Athens to claim his birthright as the only son of King Aegeus. The myths show the young man as determined to be both king and a hero. On his way to Attica, he struggled with many monsters and villains,’ and these have been likened to the Labour of Hercules.

He first killed the bandit Periphetes who killed many people with his iron mace or club. Later Theseus killed Sines, who crushed travelers by bending trees and releasing them as they passed by. As Theseus passed through Megara, he met and killed Sciron, a murderous robber who enjoys pushing people into the sea, after he had made them lick his toes.[1] He also killed Kerkyon, a king and champion wrestler, and Procrustes, who also waylaid and killed travelers.

Before arriving in Athens,’ he killed a giant sow that was causing havoc in Marathon. Upon his arrival in the city, he claimed his birth-right. The old king was pleased to see him but his wife Medea, one of Greek mythology’s most notorious women, opposed him. She tried to assassinate him several times,’ but Theseus was fortunate to support the Gods. Medea tried to do away with him by asking him to kill a monstrous bull rampaging through the countryside.[2] Theseus, to the amazement of all, killed the bull. According to some myths, Theseus also took part in Jason and his Argonauts' journey to Colchis to find the Golden Fleece.

Theseus and the Minotaur in the Labyrinth

In mythology, Athens was forced to pay King Minos on Crete a terrible tribute. Every year the Athenians had to send seven maidens and seven youths. They were to be sacrificed to the Minotaur, the freakish offspring of Queen Pasiphae and a bull. He had a human body and the monstrous head of a bull. He was imprisoned in the labyrinth that was made by Daedalus on the orders of King Minos. Theseus was determined to end the tribute and sacrifice of the young Athenians. So, he volunteered to take the place of one of the seven youths. He sailed to King Minos’ realm and was taken to the court of the king.

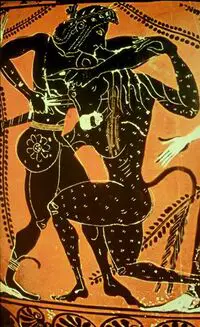

Minos' daughter Princess Ariadne immediately fell in love with the young hero. When Theseus was told to enter the labyrinth where it was expected that the Minotaur would kill him, Ariadne decided to help him. Theseus was givThe princess gave Theseus a ball of string that allowed him to mark his route in the maze. He encountered the fearsome Minotaur in the dark maze and drew a sword he had concealed. The Athenian killed the half-bull and half-man after a brutal and bloody fight.[3]

In this way, Theseus ended the terrible tribute that Athens owed to Minos. The hero escaped from Crete with Ariadne, but he later abandons her on the island of Naxos. One version of the myth claims that Theseus was ordered to do this by Artemis. Ariadne was later to marry Dionysus, who became the God of Wine and intoxication. Theseus then sailed for Athens. When he had left his father, King Aegeus promised him that he would signal that he was alive and well by hoisting a white sail instead of the usual black sail.

However, upon seeing the black sail, he forgot, and his father believed that his son was dead. In his despair, he threw himself into the sea, named after him the Aegean. Theseus became king and later united all the various settlements in Attica and merged them into a single political unit. His reign was still seen as something of a Golden Age when the Athenians enjoyed peace and prosperity. Later generations believed that he established the city’s first constitution.

Later adventures of Theseus

Despite becoming king, Theseus continued to have many remarkable adventures. In one tale, he fought the Amazon, the fabled female warriors. There are several versions of this story. In the best-known version, Theseus traveled to the land of the Amazons and seduced their Queen Antope or Hippolyta and took her back to Attica. The Amazons invaded Theseus' realm, and there was a series of bloody battles. In the decisive battle, the Queen of the Amazons was killed, and this ends the war. Among the other adventures of the hero was when he descended to the underworld to abduct Persephone from Hades, the God of the realm of death. There is also a tale that Theseus took part in the Voyage of Jason and the Argonaut.

Later, his second wife Phaedra fell in love with her stepson Hippolytos (son of the Amazon queen). Theseus heard about this and had Poseidon send a sea-monster to punish Hippolytos, who died battling the beast. In despair Phaedre, after hearing of her beloved’s death, commits suicide.[4] Theseus then decides to abduct the future Helen of Troy, when she was only a child. Her brothers the Dioscuri, rescued the child after they had invaded Attica. Theseus was forced to flee to the island of Skyros, where its king later murdered him.

In the 5th century BC, the Athenian general and statesman allegedly retrieved the king's bones and returned them to his city. Every year, a festival was held in Athens and was known as the Theseia after the Athenians consulted the Oracle of Delphi. This festival involved races and military and equestrian contests held in honor of the great Athenian hero. The purported ship that Theseus sailed on was kept in Athens harbor as a memorial to the hero and his slaying of the Minotaur. This ship was regularly repaired and refitted down the centuries, until about 300 BC.

Myth as history

Like many myths, the stories of Theseus may reflect some historical reality. Athens is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. There has been a large urban settlement where Athens now stands since the Mycenae Age. This was a Bronze Age civilization that was immortalized by Homer in his works. It is believed that there was once a Mycenaean palace on the Acropolis. There is a possibility that the cycle of myths concerning Theseus was based on a real-life Mycenaean monarch. Some have speculated that an epic was subsequently lost, which portrayed his reign and life.[5]

There is also the possibility that the legendary slayer of the Minotaur was a monarch who reigned in the Greek Dark Ages (10 and 9th century BC). There is a possibility that he was responsible for the process of syncretism. This was the merging of some settlements and villages into a city-state. He was also credited with the development of the first constitution and the system of justice. Theseus was regarded as the most important lawgiver before Solon. His reign was crucial in the history of Athens and, indeed, the wider Hellenic World. The ancient Athenians genuinely regarded Theseus as a historical figure. Some of the stories, such as the slaying of monsters and bandits, may reflect how the historical monarch brought order and the rule of law to the land of Attica.[6]

Many scholars believe that the story of Theseus slaying the Minotaur, the hero’s most celebrated feat, was also based on a historical event. The myth relates to when Athens was dominated by the Minoans, a Bronze Age civilization based on the island of Crete. Some have theorized that the tribute of youths and maidens paid by Athens to Minos indicates that the city was a dependency or a tributary of the Cretans. The myth of Theseus killing the Minotaur symbolized the Athenians' liberation from the Minoans, whom we know worshiped the bull, based on the archaeological evidence. There is another school of thought that the cycle of myths concerning the life and adventures of Theseus is an expression of Athenian values.

Unlike Hercules, the Minotaur killer was intelligent and civic-minded, as seen in his volunteering to be sent to the Palace of Minos. These are all virtues that the Athenians valued and believed made them unique. For the Athenians, the king was a demi-god, and he continued to guard their city. At the Battle of Marathon, many hoplites claimed to have witnessed the spirit of Theseus attacking the invading Persians. For many Athenians during the 5th century BC, when they were at the zenith of their power and wealth, he represented their greatness.[7]

Theseus as a cultural hero

The Greeks had a very binary view of the world. They divided things into nature/civilization and Hellenes/Barbarians. They were very aware of the fragile civilization's civilization as something that involved the subjugating and defeat of the power of chaos and forces of disorder. Theseus symbolized for many the rational forces of civilization as they battled the forces of nature and anarchy. He was a cultural hero who represented reason and order and created the conditions for civilized living.[8]

A good example of this is Theseus slaying of bandits and monsters preyed upon travelers on Greece's roads. To attack wayfarers was considered uncivilized and even sacrilegious. The king’s slaying of figures like the evil Sciron was symbolic of the civilizing process. It shows how the king brought order out of chaos and allowed civilization to grow and develop. Another good example of this was his defense of Attica against the Amazons. The female warriors were the archetypal barbarians to the Greeks because they were the opposite of everything they believed correct and civilized. Later, the Athenians compared the Persians to the Amazons to denigrate them as uncivilized barbarians.

Theseus in culture

The figure of Theseus has inspired many great works of classical art. Euripides and Sophocles both wrote tragedies based on episodes from his life. There were many representations of the Athenian king in Greek and later Roman sculpture. Theseus and his heroics were portrayed on vases, paintings, mosaics, and friezes. The Ship of Theseus in Athens later inspired a philosophical riddle on the nature of identity, which is still studied to this day.

The Romans greatly respected Theseus and likened him to Romulus. In the Renaissance, Shakespeare had Theseus as a character in the Comedy, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In the 17th Century, the great French dramatist wrote a masterpiece based on his second wife Phaedra's tragedy. In the modern era, the myths of Theseus have been portrayed in movies, TV series, and even comics.

Conclusion

Theseus is one of the most remarkable heroes in all Greek mythology. He has seen the king who laid the foundations for the greatness of Athens. Theseus was the leader who united Attica, which was a crucial step in the rise of the city-state. The character of the king may have been based on a real-life monarch. He had many remarkable journeys and achieved many feats. Perhaps his greatest was the slaying of the Minotaur.

Theseus was a cultural hero who played a key role in the civilizing process. His myths can be interpreted as the triumph of civilization over barbarism and nature. He was their founding father for the Athenians, and he was celebrated him the Archaic and Classical period. Even today, the hero and his adventures are part of popular culture.

Further Reading

Ward, Anne G., ed. The quest for Theseus. Praeger Publishers, 1970.

Kardara, Chrysoula P. "On Theseus and the Tyrannicides." American Journal of Archaeology 55, no. 4 (1951): 293-300.

Rose, D., Machery, E., Stich, S., Alai, M., Angelucci, A., Berniūnas, R., Buchtel, E.E., Chatterjee, A., Cheon, H., Cho, I.R. and Cohnitz, D., 2020. The Ship of Theseus Puzzle. Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Volume 3, 3, p.158.

References

- ↑ Graves, Robert, Greek Myths (London, Pelican, 1985), p. 132

- ↑ Graves, p. 134

- ↑ Graves, p. 143

- ↑ Graves, p. 150

- ↑ Davie, John N. "Theseus, the king in fifth-century Athens." Greece & Rome 29, no. 1 (1982): 25-34

- ↑ Osborne, M.P.. Favorite Greek Myths (London, Scholastic Inc. 1989, p. 67)

- ↑ Mills, Sophie. Theseus, tragedy, and the Athenian Empire (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 12

- ↑ Mills, p. 123