Why Were the Philistines and Israelites Enemies

Today, the term “Philistine” has become synonymous with any person or people deemed uncultured, uncouth, and boorish. The word is repeated with little thought to its origin with few people knowing that it is derived from a maligned and often misunderstood people from the Old Testament of the Bible. For those who are familiar with the Old Testament, the Philistines were at first the ultimate bullies who seemed to delight in punishing the Israelites whenever they had a chance, but they then received their just dues at the hands of Israel’s second king, David (ca. 1000 BC). The reality was that the relationship between the Philistines and Israelites was complex and requires a more thorough examination.

The Philistines and Israelites found themselves on opposite sides of the battlefield for some reasons, some of which are more obvious than others. Both peoples established kingdoms in the Levant (the region that roughly corresponds to the modern nation-states of Palestine, Israel, and Lebanon) in the early Iron Age just after the collapse of the Bronze Age system around 1200 BC. Some of the early reasons for conflict were based on culture.

The Philistines came to the Levant from the Aegean and brought with them a religion that was very different than that practiced by the Israelites, or even than what was practiced by their Canaanite neighbors for that matter. The Philistines were by nature an aggressive and expansionist people, which was ultimately the primary reason why the two peoples clashed. The Philistines expanded their influence in the region until they collided with the Israelites in the middle of the eleventh century BC. The two peoples then fought a series of wars that lasted for nearly a century, which ultimately decided who would be the dominant group in the region.

Contents

[hide]The Origins of the Philistines

Although the modern world has known about the Philistines for centuries through the Bible, their historical importance was not verified until the nineteenth century. In the decades after the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, interest in the peoples of the Bible and the biblical lands was kindled in scholars who wanted to prove or disprove, certain elements of the Bible, especially the Old Testament. Most nineteenth-century scholars were drawn to the older cultures of the Near Eastern region who had written languages and left behind monuments and architecture – such as the Canaanites, Egyptians, Hittites, and various peoples of Mesopotamia – but some of the specialists turned their attention to the more ephemeral biblical peoples.

It was during the late nineteenth century when two French Egyptologists, François Chabas and Gaston Maspero, decided to use their newly developed archaeological techniques to identify the geographical and ethnic origins of the Philistines. The two men first proposed the theory, which is now a consensus among Near Eastern scholars, that the Philistines were originally from the Aegean region of the Mediterranean Sea and probably Indo-Europeans. They based their theory on the remains of Philistine pottery in the Levant, which was nearly identical to that found in the Aegean near the end of the Bronze Age (ca. 1200 BC). [1]

The details of the manner in which the Philistines arrived in the Levant region are still unknown because they were not literate as a people at that point, but archaeology and written records from Egypt can help create a general outline of the situation. Most modern scholars believe that the Philistines were part of the wave of migrations of peoples known collectively as the Sea Peoples, who helped bring an end to the Bronze Age. In particular, the Philistines were part of the second wave of migrations/invasions that were launched on Egypt during the reign of Ramesses III (ruled 1186-1156 BC). Although Ramesses was able to repulse the invasion and take many of the Sea Peoples prisoners, it is thought that the Philistines were driven to the edge of Egypt to the coastal region of the southern Levant where they settled sometime after 1177 BC. [2] The Egyptians knew the Philistines as the “Peleset,” which over time became “Philistine,” becoming synonymous with the land in the southern Levant, which then became known as “Palestine.” [3]

Part of what made the Philistines so enigmatic was that once they arrived in the Levant, their connection to the Aegean slowly eroded. The Aegean pottery remains discovered by archaeologists demonstrates that the Philistines brought some of their cultural traditions with them across the Mediterranean, but the presence of native Canaanite pottery and other material culture shows that they were willing to adapt to their new home quickly. The presence of both Aegean and Canaanite material culture at the same dig levels has led many modern scholars to term the Philistines as a hybrid culture that kept some of their native Aegean t while adding both Canaanite traditions and people to their growing political structure. [4]

The Philistine Confederacy and Israel

The political structure of Philistine society was unique. There was no unified Philistine nation-state or even a Philistine kingdom to speak of; the Philistine people were somewhat unified by a confederacy of the five leading cities: Ashdod, Gath, Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gaza. Those cities, referred to as the “Pentapolis,” were first referenced in Joshua 13:3. Each of the five cities was ruled by a chieftain known as a seranim, which was probably an Indo-European word closely related to the Hittite word tarwanis and the classical Greek word tyrannous. [5]

The individual chieftains set the agenda in their cities, but when it came time for war, then they all met to make a group decision. It is unknown for sure which of the five cities was the most important if any were, but the Old Testament book of I Samuel 6:16 mentions that after the Philistines had taken the Ark of the Covenant from the Israelites and then suffered great calamities. As a result, they decided to return the relic to the Israelites. After the Philistines returned the Ark, “the five lords of the Philistines had seen it, they returned to Ekron the same day.” This passage implies that Ekron was the leading Philistine city, at least in the eyes of the Israelites.

By the middle of the eleventh century BC, the Philistine confederation had become powerful enough that they began to expand their influence from the coast to the east and north, which encroached on Israelite territory. [6] The first contact between the Philistines and Israelites were violent with the Philistines quickly gaining the upper hand. In the book of Judges, the Philistines are ascendant with the men of Judah even offering to bind the hero Samson, asking him: “Knowest thou not that the Philistines are rulers over us?” [7] The Philistine dominance continued, although the Israelites attempted at least one major rebellion. The Philistine and Israelite armies met at a place called Aphek in a battle that set the course of Levantine geo-politics for several following decades. According to I Samuel 13:17-19, the Philistines routed the Israelites, capturing the Ark of the Covenant and all of their iron weapons sometime between 1060 and 1050 BC. [8] Philistine dominance continued for over fifty years until King David unified Israel and Judah and finally drove the Philistines from Israelite territory in 980 BC. [9]

Cultural Conflict between the Philistines and Israelites

Although the primary source of conflict between the Philistines and Israelites was the age-old quest for land and dominance, culture clash also played a role. The most explicit example of this conflict is related in I Samuel after the Philistines defeated the Israelite army and brought the Ark of the Covenant to Ashdod, then to Gath, before returning it to the Israelites. In the ancient Near East, most of the sedentary peoples kept a statue of their most important deity in the deity’s temple. The statues, known by modern scholars as “cult statues,” were only allowed to be viewed by the high-priests and were often a target by invading armies. The more warlike peoples of the ancient Near East, such as the Assyrians, would collect their enemies’ cult statues as mementos and as a psychological weapon.

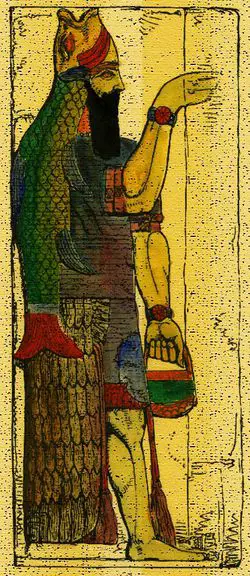

The Ark of the Covenant was the equivalent of the Israelites’ cult statue, so it is no wonder that the writers of the Old Testament reserved great scorn for the Philistines and their primary god, Dagon after their “cult statue” was taken. Little is known about the god Dagon, but modern scholars believe he was a male variant of an Indo-European earth goddess. [10] It is important to note that unlike Bal and some other Canaanite and Semitic gods, the Old Testament never mentions renegade Israelites worshipping Dagon. The Philistines and their culture were anathemas to the Israelites.

Conclusion

The conflicts between the Philistines and Israelites is well-known from many books and passages in the Old Testament of the Bible. The two peoples shared animosity for each other that was the result of a couple of factors. The two groups had different cultural origins and worshipped different gods, which was one of the sources of their conflicts, but added to the intensity of their wars more than anything. The primary reason why the Philistines and Israelites were enemies was due to both peoples desiring to put the Levant under their political hegemony. The Philistines got the upper hand first, but then the Israelites became the primary force in the region by the early tenth century. In the end, both sides were eventually defeated when the mighty Assyrian Empire overwhelmed the entire Levant and made them both vassals.

References

- Jump up ↑ Dothan, Trude, and Moshe Dothan. People of the Sea: The Search for the Philistines. (New York: Macmillan, 1992), pgs. 25-26

- Jump up ↑ Kitchen, Kenneth. The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt: (1100 to 650 BC). Second Edition. (Warminster, United Kingdom: Aris and Phillips, 1995), pgs. 140-1

- Jump up ↑ Cline, Eric H., and David O’Connor. “The Mystery of the ‘Sea Peoples.’” In Mysterious Lands. Edited by David O’Connor and Stephen Quirke. (London: University College London Press, 2003), p. 116

- Jump up ↑ Yasur-Landau, Assaf. The Philistines and Aegean Migration at the End of the Late Bronze Age. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 240

- Jump up ↑ Yasur, p. 312

- Jump up ↑ Dothan and Dothan, p. 150

- Jump up ↑ Judges 15:10

- Jump up ↑ Kuhrt, Amélie. The Ancient Near East: c. 3000-330 BC. Volume 2. (London: Routledge, 2010), p. 440

- Jump up ↑ Dothan and Dothan, p. 138

- Jump up ↑ Singer, Itamar. “Towards the Image of Dagon the God of the Philistines.” Syria 69 (1992), p. 445