How Did Lullabies Develop

Putting a crying baby to sleep is hard as any parent likely knows. This has been an age old problem that is evident from a long history of parents attempting to put their children to sleep using song or music as an aid. The history of this starts soon after recorded history began and it is clear the problem of getting children to sleep has been going on for many cultures across time.

Early History of the Lullaby

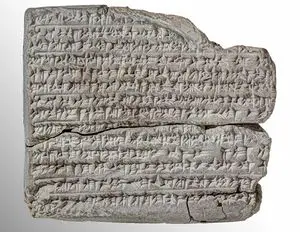

Lullabies, undoubtedly, have been around since prehistoric periods. Some scientists suggest lullabies evolved as humans had to multitask and try to get their babies to sleep while also moving in the landscape and needing their hands to be free for other activities. Whatever the reason, we know getting babies to sleep is an ancient problem. The earliest lullabies recorded are from Babylonia, in modern day southern Iraq, where the lullabies are not only songs to help babies sleep but they have characteristics we may find somewhat menacing (Figure 1). There are a number of lullabies from Babylonian; one of the works mention that the baby has cried and is waking up and disturbing the house god who becomes angry with the baby so baby should go back to sleep.

Other lullabies from Babylonia were even darker, with threats that the baby would be eaten. While this may sound harsh to us, we should keep in mind of course many lullabies, including our own, have dark undertones such as death or pain caused to the child. Lullabies, with their melancholy rhythm, often have dark undertones in many cultures and that has stayed relatively consistent from their origin. Lullabies were also used as a basis to create magic spells used by Babylonians to help ward evil. So it may have been that saying bad or harmful things was intended to do the opposite, which was to protect the baby from evil spirits. Even in some modern cultures today, curses that ward bad spirits are said using often dark or menacing themes.

In Egypt, in a mid-second millennium BCE lullaby, called Magical Lullaby, the lyrics talk about protecting a child from evil spirits. Spells in Egypt involved some spell recitation, ritual, and a magician to be involved; however, lullabies seem to be one type of spell or magic that even normal people could practice. Thus, lullabies may have been seen as a type of spell one attempts to not only put baby to sleep but also protect baby from evil in the night. It was also important to cast the spell properly so lullabies were important for their words of protection as well as the tunes or rhythm they carried. In fact, it may have been the evil spirits that were responsible in making a baby cry so the soothing voice helped protect with that protection putting a baby to sleep.[1]

In the Greco-Roman world, similarly lullabies often had negative connotation and were equated or incorporated with magic or spells that the singer would seemingly try to induce to help protect babies. Night would have been seen as potentially a very vulnerable period for a baby and songs would help sooth a baby but also the lyrics were intended to act as spells to help protect a baby from the darkness, which was equated with harmful things that may inflict a young baby. Scholars have, in fact, suggested that lullabies were effectively spells against evil spirits and the soothing sounds were seen as evidence that such spells may have helped babies sleep and avoid the harm that night may cause on a child.[2]

Later Developments

During the Medieval and early modern period, it is likely many lullabies we know, such as Rock a Bye Baby and Highland Fairy Lullaby developed. Interestingly, many themes we see in the earliest lullabies remained (Figure 2). As with early societies, fear of the dark and its potential evils on a child seem to prevail in the words of most lullabies. The songs themselves are soothing but lyrics regarding danger, death, and even babies being stolen by thieves are common lyrics in not only the lullabies we know but also those that have been recovered from historical texts.

The origin of lullabies such as Rock a Bye Baby are generally unknown; one theory has been that this lullaby originated from observations of Native Americans using tree branches to suspend cradles from. The fear of branches breaking and a baby falling from a tree is possibly reflected by this observation. We also see more themes of animals, such as counting or singing about sheep, in lullabies that developed in Europe.[3]

Cross cultural comparisons of lullabies also indicates a fear of the dark and unknown is a common theme in lullabies. For instance, in Iceland Bíum Bíum Bambaló, which has also been sung recently by an Icelandic band, is a terrifying lullaby about a face lurking outside and looking at the window. Fear of what is waiting for baby and with the baby possibly taken if the baby goes outside is a key theme. Even in the New World, lullabies developed to be menacing in their lyrics. For instance, Dodo Titit is a Caribbean lullaby that talks about a crab eating a baby. In Brazil, the lullaby Nana Nenê is about an alligator named Cuca that might get the baby if he or she stays noisy or cries. In Indonesia, an old lullaby of uncertain date reflects a roaming giant on the island that searches for crying babies.

Interestingly, in Japan, rather than scary themes, lullabies are often more melancholy, reflecting a mother longing or missing her child. Lullabies such as Itsuki reflects a mother missing her child as she is away, although even here there is fear in the lullaby. In this case, the fear is if the mother dies then the dilemma might be who would take care of the baby.

In Malaysia, no harm happens to the baby but baby chicks seem to die in the lyrics during a count down of numbers. Overall, we see a kind of sad or depressing but often frightening theme to lullabies. This also could reflect the melancholy nature of many tunes.

In the United States, Hush Little Baby is perhaps among the best known lullabies that developed in the early history of the United States in the southern part of the country. Here, however, the lyrics are not frightful but promise reward for the baby if he or she just goes to sleep. Nevertheless, even here accidents and problems with things breaking seems to happen.[4]

The Modern Lullaby

Many modern lullabies, of course, are based of their ancient or older counterparts, with themes often focused on fear, lurking dark creatures, or even death. However, studies do also show that lullabies in the past and modern period have beats that do help babies calm their hearts and that a song in a quiet tone with humming often has the effect of relaxing muscles and reducing blood pressure. Lullabies that have been composed recently often do not have the same melancholy or depressing nature of earlier works, although sometimes they do, while a modern rhythm and tunes accompany these works. Works such as Azure Ray have lyrics about not being able to sleep, but the tune appears to be more happy. Even old lullabies such as Rock a Bye Baby or Hush Little Baby have been adapted with often less melancholy beats.

Many parents today have been using more upbeat modern songs and either modifying them or simply playing them at a lower level to get their babies to sleep. However, some sleep therapist and doctors do not think all of these works might be appropriate. Recent research does suggest having a more melancholy beat and rhythm helps with sleep. There might be something about those old lullabies then, even if their lyrics are frightful or depressing, in that they generally create the type of sounds that help put babies to sleep more easily and also help relax babies so that their sleep is more efficient and beneficial.[5]

Summary

Lullabies are more ancient than recorded history but even within recorded history they are evident from some of the earliest periods. From the earliest lullabies recorded in Mesopotamia and Egypt, songs were frightful and often full of frightening demons or gods that could eat or terrify anyone, including babies. Such themes continued and many early lullabies were probably prayers or forms of magic sayings that were intended to help ward evil spirits away from babies, which were seen as active at night. Even more recent lullabies, such as the popular Rock a Bye Baby, is full of terror and potential pitfalls for baby. Only in recent periods do we see more upbeat lullabies; however, some medical scientists question if such lullabies are as effective and potentially melancholy tones and sounds might be more useful in calming babies' minds and hearts as they fall into sleep.

References

- ↑ For more on some of the earliest lullabies, such as from Egypt and Mesopotamia, see: Marek, D., 2007. Singing: the first art. Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Md.

- ↑ For more on Greco-Roman lullabies, see: Frankfurter, D., 2015. The Great, the Little, and the Authoritative Tradition in Magic of the Ancient World. Archiv für Religionsgeschichte 16. https://doi.org/10.1515/arege-2014-0004

- ↑ For more on origins of some well-known lullabies in the English-speaking and Western world, see: Van der Walt, T., Fairer-Wessels, F., Inggs, J. (Eds.), 2004. Change and renewal in children’s literature, Contributions to the study of world literature. Praeger, Westport, Conn.

- ↑ For more on cross-cultural comparisons and reasons for given lullabies lyrics and tunes, see: Achté, K., Fagerström, R., Pentikäinen, J., Farberow, N.L., 1990. Themes of Death and Violence in Lullabies of Different Countries. Omega (Westport) 20, 193–204. https://doi.org/10.2190/A7YP-TJ3C-M9C1-JY45

- ↑ For more on how lullabies affect our mental state, see: Hellberg, D. 2015. Rhythm, Evolution and Neuroscience in Lullabies and Poetry. Association for the Study of Ethical Behavior/Evolutionary Biology in Literature 11 (1)