Difference between revisions of "Who was Asclepius: Greek god of medicine"

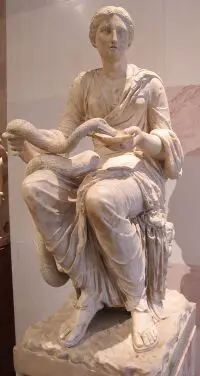

(Created page with "200px|thumbnail|left|A statue of Asclepius__NOTOC__ In the Graeco-Roman world, religion and medicine were closely intertwined. Medical treatments w...") |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 19:28, 20 July 2021

In the Graeco-Roman world, religion and medicine were closely intertwined. Medical treatments were basic at best, although some were based on empirical evidence and had some benefits. Because of the lack of medical knowledge, many people had to rely on religion and rituals for medical treatment.

Asclepius was the Greek god of healing, medicine, and medical practitioners. He was one of the most important gods in the Greco-Roman World, and there were many shrines and sanctuaries to this deity. Understanding this god can help us understand not only ancient beliefs but also the evolution of medicine.

Where did Asclepius come from?

There are some indications that Asclepius originated in pre-Greek times. In most myths, Asclepius was Apollo's son, the god of light, prophecy, art, and healing. His mother was reputed to be Coronis. She was later killed by Apollo’s sister Artemis because she was unfaithful to god. Coronis was pregnant when she died, and as she was about to be cremated on a funeral pyre, his father rescued the unborn Asclepius. The Romans believed that Apollo killed his human lover, who did not know she was pregnant. In one legend, he took her to a temple dedicated to him where Asclepius was born. His birth name was Hepius.

Another legend has it that Asclepius been exposed by his mother but was saved by Apollo. The God reared the infant and taught him the art of healing. Later he was educated by a centaur. In one myth, the young Asclepius's ears were licked by a serpent who had saved the creature. Like the Romans, the snake was a sacred animal associated with wisdom, healing, and resurrection to the Ancient Greeks.

In one myth, a snake brought a herb to him. From then on, Asclepius carried a staff that was twinned by a snake. At this stage, Asclepius was still a mortal, although one that was gifted. The future god used herbs to cure a king called Anscines, which led him to be called Asclepius. Soon he was famous as a healer, as great as his father. In the myth of the Calydonian Boar, a monster from the underworld, who terrorized parts of Greece, he played a prominent role.

Asclepius's fame as a healer grew, and many people flocked to him, seeking his help. He acted more like a doctor at this stage as he was still a human despite his father being Apollo. It is claimed that he used his skills to resurrect several heroes and kings from the dead, and these include Tyndareus and Lycurgus.

However, this caused problems with the Greek Gods, especially Hades, the Lord of the realm of the dead. Because Asclepius was saving so many from death, he had fewer subjects. This meant that Hades had far fewer subjects, and he asked Zeus to intervene. The King of the Gods was concerned because the son of Apollo was upsetting the natural and ordained balance. [1] He was making too many people immortal, and only the Gods could enjoy this status.

In particular, he was afraid that Asclepius could teach other humans the secrets of beating death. Zeus struck the healer dead with a lightning bolt. His father was enraged and killed some Cyclopes who had forged the bolts. Zeus expelled Apollo from heaven and forced him to become a slave of a king, but they were later reconciled. The god of light beseeched the Father of the Gods to resurrect Asclepius, whom the Father of the Gods, had lain in a constellation in the heavens. Remarkably Zeus agreed and raised the dead healer, making him a deity and admitting him to Olympus. The King of the Olympians raised the healer not only to please Apollo but as part of some divine plan, which he kept secret.[2]

Asclepius was married to Epione, who was the Greek goddess of soothing or pain relief. With her, he had five daughters who were also associated, in one way or another, with health and healing and who all represent some facet of medicine. Among the daughter was Hygieia, a goddess of healing from whom the word hygiene comes from. Another daughter was Panacea, was the Goddess of universal treatment. Asclepius also had three sons, and two of them were renowned healers, Machaon and Podaleirios, who both led armies in the Illiad.[3] One of the brothers, Machaon, is regarded as the demi-god of surgery.

How did the belief in Asclepius impact the development of medicine?

By the 5th century BC, the cult of Asclepius was prevalent in the Greek world, not surprising since, given the poor diets and lack of hygiene, the disease was common. There were many temples and shrines dedicated to the god, and the most famous of these were on the island of Cos and at Epidaurus, where every four years, games were held in the son of Apollo’s honor. These were Pan-Hellenic centers, and people came from all over the Greek world to these sites. Asclepeions, as they were known, were not just traditional temples but also healing centers.

This was based on his reputation as a demi-god of healing and medicine. At these sites, a form of faith-healing took place. Non-venomous snakes that were believed to be sacred to God and to have special powers were allowed to slither freely around the temple area. The sick would visit the Asclepeions, and they would be ritually purified in the ritual known as the Katharsis.[4]

Then the patients or devotees were encouraged to engage in the practice of incubatio, also known as 'temple sleep.’ During these periods of sleep, the god was believed to appear to the sick person. The priests of Asclepius then interpreted these dreams. These typically involved performing some ritual and making changes to their lifestyle, such as eating less and exercising more, like a modern doctor. Pilgrims to the Asclepeions were often very pleased with the results. We have many records stating that they had been ‘cured.’[5]

During pandemics, these Temples and shrines were thronged with the afflicted seeking help from Apollo's son. Over time the priests and their assistants, known as the Therapeutae of Asclepius, became more like physicians, although they continued to perform their sacred duties. It appears that during the Hellenistic period that many began to perform surgeries and even had some basic knowledge of the anesthetic properties of plants and herbs. These priests became very familiar with various sicknesses and their symptoms and became very skilled.

Over time the Asclepeions became akin to ancient medical schools. Hippocrates, often regarded as the preeminent doctor in the Ancient World, is believed to have studied at the famous temple of Asclepius on Kos. Many of the ideas he learned he expanded upon in his famous theories influenced medical practitioners for 1000 years in the West. Another one of the pioneers of medicine Galen. He studied medicine and anatomy in the Greek city of Pergamum (in modern Turkey). The God of Medicine's importance can be seen that the original Hippocratic oath included a reference to Asclepius.[6]

Did the Romans accept Asclepius?

The Romans were deeply influenced by Greek religion and adopted the cult of Asclepius. There is evidence that many Romans visited the Asclepeions, and they adopted many of the practices. It appears that the god was introduced into Rome in 293 BC. This was highly symbolic as it was associated with Greek medicine's official acceptance in the Roman Republic. Before the Cult of Asclepius, the head of the family in Rome performed medical treatment in the household. Greek doctors soon began to dominate the medical profession in Rome and its provinces, despite conservatives such as Cato.

The Romans absorbed Greek medical knowledge and soon began to build charitable and military hospitals by the 1st century BC. They were probably in part based on the medical facilities at the Asklepion. A distinctive Roman institution was the collegium. These were legally recognized groups that performed some social functions. Many were dedicated to the Imperial Cult. One of the most important in Rome was the College of Aesculapius and Hygia. Interestingly the Imperial Cult became associated with Asclepius.[7] This was designed to show Emperors such as Vespasian as healers.

Here, we see how the mythology of the deity of healing and medicine became used by the political elite to legitimize Rome's rule. For example, Vespasian and Titus of the Flavian Dynasty used imagery associated with the god to demonstrate how they have ‘healed’ the Empire after the civil war. The Staff of Asclepius is now widely used as a symbol for many medical organizations. It is possible that early Christians were influenced by Asclepeions when they were developing their early hospitals, especially in the Eastern areas of the Roman Empire.

What is the meaning of the Asklepion myths?

Apollo was the god of healing and medicine in the Graeco-Roman World; however, he was more concerned with magical healing. On the other hand, Asclepius was a God of healing using a mixture of religion and practical skills. Unlike Apollo, it was believed that Asclepius was the hero who developed the skills of medical treatment. He was associated with medical procedures and herbs.

For the Greeks and Romans, over time, he came to represent medical knowledge and skills. He was the healer of humans and had been given and learned the knowledge of healing. He can be equated with cultural heroes who provided humans with practical skills that they needed to survive and prosper in many ways. Asclepius helped heal humans, but he helped them learn the techniques and wisdom to live healthy and full lives. Asclepius embodied wellbeing.

Interestingly the healing offered by the god was holistic, as is evident from the treatments recommended in his temples. Holistic healing was deemed the most desirable route to welling being. This is something that modern medicine has only recently embraced. The mythology of Asclepius also reveals much about the Greek and Roman worldview. His tales show that humans can help themselves and that health and wellbeing are within their power.

However, as seen in the story of Asclepius's death, not even the God of healing is permitted to save humans from death. Therefore, people couldn't become immortal, and this was ordained by nature and the Gods. The tales of the deity of healing can be understood as another example of mortality and immortality in Classical Mythology. It is that which is inevitable for humans and what makes them the inferior of the Gods. The story of Asclepius's death once again warned the Ancients that they must accept their mortality or else they faced the wrath of the deities, a recurring theme in many myths [8].

Conclusion

Asclepius played a significant role in the Ancient World. He was a deity who was associated with many superstitious practices that were thought to help the sick. In the pre-scientific age, people had no choice but to resort to rituals and magic. However, out of the cult of Asclepius, practices, and beliefs that prefigured modern medicine and his temples played a role in the development of the modern hospital.

The priests of Asclepius became the forerunners of modern medical practitioners. It is ironic that Apollo's son's temples and shrines, with their strange practices such as letting snakes go wild, were also key to the foundation of modern ideas about medicine. The myths of Asclepius help us to understand what the ancient thought about medicine and health. Medical treatment was a skill that was imparted by the divine.

Further Reading

Filippou, Dimitrios, Gregory Tsoucalas, Eleni Panagouli, Vasilios Thomaidis, and Aliki Fiska. "Machaon, son of Asclepius, the father of surgery." Cureus 12, no. 2 (2020).

Cavanaugh, Thomas A. Hippocrates' Oath and Asclepius' Snake: The Birth of the Medical Profession. Oxford University Press, (2018).

Steger, F. "Asclepius: Cult and medicine." History of Medicine, 6(3), 176-187, (2019).

References

- ↑ Burkert, Walter, Greek Religion (Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, 1985), p. 113

- ↑ Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths (Pelican, London, 1990)

- ↑ Homer: Iliad Book 4.193-94: 218-219

- ↑ Wilcox, R. A. & Whitham, E. M. The symbol of modern medicine: why one snake is more than two. Annals of Internal Medicine, 138 (2003), pp 673-677

- ↑ Edelstein, L. & Edelstein, E. Asclepius: A collection and interpretation of the testimonies. (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1988), p. 12

- ↑ Wilcox, R. A. & Whitham, p. 178

- ↑ Wickkiser, B. Asklepios, medicine, and the politics of healing in fifth-century Greece: Between Craft and cult (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 2008), p. 13, 56

- ↑ Burkhardt, p. 119, 203