Difference between revisions of "What was the impact of the Emperor Nero on the Roman Empire"

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

Nero was the first Roman Emperor to actively persecute the small sect of Christians. They had grown greatly since the crucifixion of Jesus. They had established themselves in Rome and they had managed to attract many followers. They were not popular with other groups and their beliefs were treated with suspicion. They were after all self-confessed followers of Jesus who had been lawfully executed by the governor of Judea <ref> Tacitus. Annals of Imperial Rome. 67</ref>. In 69 AD a great fire swept through Rome and cause great unrest in the city. It is widely believed that Nero made scapegoats out of the Christians in the city <ref> Holland, p. 334</ref>. According to Tacitus, he was very eager to quell rumours that he was responsible for the fire ‘ consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called "Christians" by the populace’ <ref> Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome. 15. 44</ref>. Nero established a precedent whereby an Emperor could declare the Christians to be public enemies. Nero’s and later persecutions were to shape the nature of Christianity but it did not stop its spread. The many martyrs created by the persecutions only strengthened the faith and it eventually became the state religion of the Empire in the later 4th century AD. | Nero was the first Roman Emperor to actively persecute the small sect of Christians. They had grown greatly since the crucifixion of Jesus. They had established themselves in Rome and they had managed to attract many followers. They were not popular with other groups and their beliefs were treated with suspicion. They were after all self-confessed followers of Jesus who had been lawfully executed by the governor of Judea <ref> Tacitus. Annals of Imperial Rome. 67</ref>. In 69 AD a great fire swept through Rome and cause great unrest in the city. It is widely believed that Nero made scapegoats out of the Christians in the city <ref> Holland, p. 334</ref>. According to Tacitus, he was very eager to quell rumours that he was responsible for the fire ‘ consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called "Christians" by the populace’ <ref> Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome. 15. 44</ref>. Nero established a precedent whereby an Emperor could declare the Christians to be public enemies. Nero’s and later persecutions were to shape the nature of Christianity but it did not stop its spread. The many martyrs created by the persecutions only strengthened the faith and it eventually became the state religion of the Empire in the later 4th century AD. | ||

==Nero’s policies in the East== | ==Nero’s policies in the East== | ||

| − | Nero was a far more active Emperor than many gave him credit for at the time and since. He was particularly interested in the East. His record here was mixed. Nero attempted to permanently annex the Bosphoran Kingdom in the Crimea but his successors reversed this and were content to have it as a client kingdom. Nero fought a war with Parthia. He appointed a commoner to lead the Roman armies and he managed to inflict several defeats on the Parthians <ref> Suetonius. Life of Nero. 43</ref>. Nero was able to turn the strategic kingdom of Armenia into a client kingdom and this allowed him to secure the borders with Parthia. He also obliged the Parthians to hand over some legion ‘eagles’ or standards that had been captured. Nero’ s success against the Parthians meant that the Eastern frontier was at peace for several decades <ref> Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome, 56</ref>. However, during his reign the administration of Judea was poor and this contributed to the great Jewish Revolt (66-71 AD). The Jewish historian stated that the Jews believed him to be a ‘tyrant’ <ref> Josephus. History of the Jewish War, ii</ref>. Perhaps his most lasting legacy was his generally pro-Greek policies in the Eastern half of the Empire. He granted ‘liberties’ to many Greek cities in the eastern portion of his empire. This led them to become economically successful and culturally vibrant <ref> . This partly explains why unlike the west that the east did not succumb to Romanization but remained very much influenced by Hellenic culture. Later emperors such as Hadrian imitated Nero’s policies towards the Greek cities. | + | Nero was a far more active Emperor than many gave him credit for at the time and since. He was particularly interested in the East. His record here was mixed. Nero attempted to permanently annex the Bosphoran Kingdom in the Crimea but his successors reversed this and were content to have it as a client kingdom. Nero fought a war with Parthia. He appointed a commoner to lead the Roman armies and he managed to inflict several defeats on the Parthians <ref> Suetonius. Life of Nero. 43</ref>. Nero was able to turn the strategic kingdom of Armenia into a client kingdom and this allowed him to secure the borders with Parthia. He also obliged the Parthians to hand over some legion ‘eagles’ or standards that had been captured. Nero’ s success against the Parthians meant that the Eastern frontier was at peace for several decades <ref> Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome, 56</ref>. However, during his reign the administration of Judea was poor and this contributed to the great Jewish Revolt (66-71 AD). The Jewish historian stated that the Jews believed him to be a ‘tyrant’ <ref> Josephus. History of the Jewish War, ii</ref>. Perhaps his most lasting legacy was his generally pro-Greek policies in the Eastern half of the Empire. He granted ‘liberties’ to many Greek cities in the eastern portion of his empire. This led them to become economically successful and culturally vibrant <ref> Holland, p. 324</ref>. This partly explains why unlike the west that the east did not succumb to Romanization but remained very much influenced by Hellenic culture. Later emperors such as Hadrian imitated Nero’s policies towards the Greek cities. |

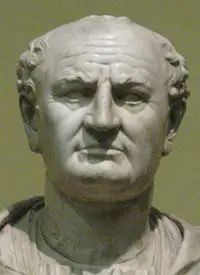

[[File:Vespasianus02 pushkin.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Bust of the Emperor Vespasian]] | [[File:Vespasianus02 pushkin.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Bust of the Emperor Vespasian]] | ||

Revision as of 18:05, 4 May 2017

Contents

Introduction

Roman history was noted for having very many ‘bad’ emperors. One of the most notorious of these is Nero. He was the last of the Julian-Claudian dynasty and became infamous for his artistic pretensions, hedonism and his great cruelty. There are many myths about Nero and this often obscured the reality of his reign. The emperor was a very important figure in the history of Rome. He was the last of his dynasty and his death ushered in a period of instability. His death led to a period of civil war the first in almost one hundred years. Nero was the first to persecute Christians and he set a precedent for that groups persecution that was to last on and off for almost three centuries.

Background

Augustus had brought peace to the Roman Empire and during his reign he amassed a range of powers. He made himself in effect the first Emperor [1]. Such was his prestige and the Roman’s fear of instability that they accepted his step-son, Tiberius as his successor [2]. This established the hereditary principle in regard to the Imperial succession and the Julian-Claudians were the de-facto royal house of the Empire. Tiberius, who is often portrayed as a depraved and bloody old man, was in fact a very capable leader. He reformed the system of governance and tax-collection and his rule was mild. By the time of his death the hereditary principle was successfully established and his nephew Gaius (Caligula) became Emperor [3]. His four years in power were bizarre and bloody and after his assassination he was succeeded by Claudius. Often portrayed as something of a fool in fact he was another capable leader. He ordered the conquest of Britain and also annexed much of modern-day Morocco for his empire[4]. In the first-century AD the Empire was at its zenith. There had been peace for several decades and the borders were relatively secure. The majority of provincials were loyal to the Empire and they were increasingly Romanized. The economy of the Empire was generally good. There was also a great cultural flourishing and poets such as Ovid and writers such as Petronius, produced masterpieces of Latin literature that are still read to this day. This was the Empire that Nero inherited [5] .

The life and reign of Nero

It is important to note that there are no surviving contemporary records of Nero and that many of the surviving accounts are possibly biased. Nero was born in 37 AD. His parents were Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, a member of one of the most powerful Roman families and Agrippina the Younger, sister of Emperor Caligula. He was a grant-nephew of Augustus and therefore a member of the Julian-Claudian family. Nero was not viewed as a future emperor at the time of his birth [6]. During the reign of his uncle Caligula, his mother fell from favour and the family were persecuted. His father died (of natural causes) and his mother was exiled. Nero’s fortunes changed with the assassination of his uncle Caligula. Claudius became Emperor and after a disastrous marriage he married Agrippina the Younger, his niece [7]. She was able to persuade Claudius to make her son Nero his heir and he married the daughter of Claudius from his first marriage. It is widely believed that Agrippina, probably with the help of Nero poisoned Claudius. Nero became Emperor in 54 AD at the age of seventeen [8]. His mother, was a domineering woman and it is believed that she manipulated her young son to advance her own interests. The first five years of Nero’s reign were seen as generally positive. The government was in the hands of two experienced ministers one of whom was the writer Seneca the Younger, the other Burrus [9]. Agrippina the Younger vied for control of the empire with Seneca and his colleague but they remained in control. In 55 B.C it seems that Nero wanted to control the Empire and he has Seneca and Burrus dismissed. Later he killed his mother, he was tired of her constant efforts to dominate him and to become the power behind the throne [10]. This apparently led to a great change in Nero’s character and according to the ancient sources he became a grotesque tyrant. Nero began to murder any senator who opposed him. His personal life was bizarre and he married one of his male slaves. Nero was passionate about the games and he personally participated in the Olympic games in Greece [11]. The Emperor considered himself to be first and foremost an artist. He at first performed his work in private but then publicly performed his work in Greece. Nero also acted on the stage. This scandalized the Roman elite who considered actors to be little better than prostitutes and the sight of Nero acting was unacceptable to them. Nero was paranoid about plots and he killed anyone he suspected of being a threat. While Nero was very unpopular with the elite he was popular with the poor. He reformed the judicial and taxation system and made it fairer. Nero also built gymnasiums and baths in Rome that were open to ordinary Romans. The population of Rome and elsewhere in the Empire revered the Emperor and saw him as their protector. According to Suetonius, the emperor was ‘carried away by a craze for popularity and he was jealous of all who in any way stirred the feeling of the mob’ [12]. The emperor needed the acclaim as according to the philosopher Epictetus, he was an insecure, immature and unhappy man’ [13]. Nero was a lavish builder and some sources say that he left the treasury bankrupt but others believe that his spending was part of a policy to revive a stagnant economy. In 66 AD, a great fire destroyed much of Rome [14]. The cause of the fire is not known and it may have been accidental or it may have been arson. Many blamed Nero for the fire and he was accused of starting it in order to secure land for his building projects. It seemed that by 68 AD, Nero had begun to raise taxes and there were many reports of growing discontent among the elite. While in the east there was a major Jewish Revolt and the Romans had been expelled from much of Judea. In 68 AD Vindex in Gaul revolted but was later put down, by the Roman legions [15]. It seems that for whatever reason that the army had grown tired of Nero even though he was a member of the House of Julius Caesar and Augustus [16] . In Spain Galba and the Spanish legions revolted and this was generally welcomed by many of the elite in Rome [17]. Galba set sail for Rome and Nero tried to rally his forces. However, he had alienated the elite and he was soon abandoned. Nero fled with some slaves but later committed suicide, by ordering a slave to cut his throat[18] Nero remained popular with the poor and after his death there were three pretenders who claimed they were actually the Roman Emperor.

The Year of the Four Emperors and the end of the Julian-Claudian dynasty

It seems that Nero’s reign had destabilized the Empire. His low tax policy combined with his lavish spending had led to an economic recession. He had also alienated the elites in Rome and elsewhere. He had also failed to provide strong government as is evident in the revolt of Vindex in Gaul and the Jewish Revolt. In the aftermath of his death, unlike that of his unstable uncle Caligula, there was no living male who was a member of the Julian-Claudian line [19]. The Julian-Claudian had killed many of their relatives and as a result after the death of Nero, who had no sons, there was no legitimate claimant to the throne. This left the army as the power broker and in the year after the suicide of Nero the legions fought for control of the Empire[20]. The year 69 AD is often known as the year of the ‘Four Emperors’. In that year four men, Galba, Otho, Vitellius and Vespasian declared themselves emperor. Vespasian emerged as the victor and he established the Flavian dynasty [21]. Nero had killed the last male in the Julian-Claudian line and did not have his own son. This meant that with his death that his dynasty which had been so successful came to an end. He left a power vacuum which was filled by competing generals and that led to a series of civil wars. Nero’s reign was to see the re-emergence of the Roman army into politics for the first time in a century. The year 69 AD was important as it showed that the army could make and unmake an emperor and this was to be a destabilizing factor in Roman politics until the fall of the western Roman Emperor [22].

Nero and the Christians

Nero was the first Roman Emperor to actively persecute the small sect of Christians. They had grown greatly since the crucifixion of Jesus. They had established themselves in Rome and they had managed to attract many followers. They were not popular with other groups and their beliefs were treated with suspicion. They were after all self-confessed followers of Jesus who had been lawfully executed by the governor of Judea [23]. In 69 AD a great fire swept through Rome and cause great unrest in the city. It is widely believed that Nero made scapegoats out of the Christians in the city [24]. According to Tacitus, he was very eager to quell rumours that he was responsible for the fire ‘ consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called "Christians" by the populace’ [25]. Nero established a precedent whereby an Emperor could declare the Christians to be public enemies. Nero’s and later persecutions were to shape the nature of Christianity but it did not stop its spread. The many martyrs created by the persecutions only strengthened the faith and it eventually became the state religion of the Empire in the later 4th century AD.

Nero’s policies in the East

Nero was a far more active Emperor than many gave him credit for at the time and since. He was particularly interested in the East. His record here was mixed. Nero attempted to permanently annex the Bosphoran Kingdom in the Crimea but his successors reversed this and were content to have it as a client kingdom. Nero fought a war with Parthia. He appointed a commoner to lead the Roman armies and he managed to inflict several defeats on the Parthians [26]. Nero was able to turn the strategic kingdom of Armenia into a client kingdom and this allowed him to secure the borders with Parthia. He also obliged the Parthians to hand over some legion ‘eagles’ or standards that had been captured. Nero’ s success against the Parthians meant that the Eastern frontier was at peace for several decades [27]. However, during his reign the administration of Judea was poor and this contributed to the great Jewish Revolt (66-71 AD). The Jewish historian stated that the Jews believed him to be a ‘tyrant’ [28]. Perhaps his most lasting legacy was his generally pro-Greek policies in the Eastern half of the Empire. He granted ‘liberties’ to many Greek cities in the eastern portion of his empire. This led them to become economically successful and culturally vibrant [29]. This partly explains why unlike the west that the east did not succumb to Romanization but remained very much influenced by Hellenic culture. Later emperors such as Hadrian imitated Nero’s policies towards the Greek cities.

Conclusion

Nero is regarded as either a mad or outright evil Emperor. He was undoubtedly cruel and committed many crimes. However, he was also an important figure in the history of Rome. Nero was the first Emperor to persecute Christians and many other Emperors were to follow his example. He also had some successes in the east especially against the Parthians and he did much to promote Hellenic culture in the eastern provinces. He was the last of the Julian-Claudian dynasty and his death led to a series of bloody civil wars. This period of instability led to the army determining who should be emperor. This was one of the most important legacies of Nero the re-emergence of the legions as a political force, something that Augustus and his heirs had prevented for several decades.

References

- ↑ Tacitus. Annals of Rome. 1

- ↑ Suetonius. Life of Tiberius. 4

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Caligula. 8

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Claudius, 8

- ↑ Griffin, Miriam T. Nero: The End of a Dynasty ( London: Yale University Press, 1985), p 12

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Nero. 5

- ↑ Tacitus. Annals of Rome. 34

- ↑ Suetonius. Life of Claudius. 62

- ↑ Tacitus, The Annals of Imperial Rome, 45

- ↑ Griffin, p 123

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Nero. 34

- ↑ Suetonius. Life of Nero. 53

- ↑ Arrian. Sayings of Epictetus. 56

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome, 56

- ↑ Tacitus. The Histories. 45

- ↑ Holland, Richard. Nero (The Man Behind the Myth. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000), p 145

- ↑ Suetonius. Life of Galba, 7

- ↑ Suetonius, Life of Nero, 54

- ↑ Holland, Tom. Dynasty. The rise and fall of the house of Caesar (London, Little Brown, 2015), p. 347

- ↑ Holland, p. 349

- ↑ Holland, p. 406

- ↑ Holland, p. 412

- ↑ Tacitus. Annals of Imperial Rome. 67

- ↑ Holland, p. 334

- ↑ Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome. 15. 44

- ↑ Suetonius. Life of Nero. 43

- ↑ Tacitus. The Annals of Imperial Rome, 56

- ↑ Josephus. History of the Jewish War, ii

- ↑ Holland, p. 324