Difference between revisions of "The Power of Women and Peru's Shining Path"

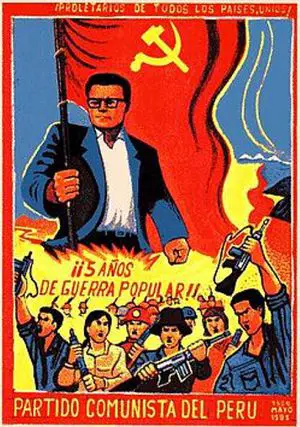

(Created page with "__NOTOC__ thumbnail|300px|left|Shining Path Poster from 1985 The war between the Shining Path and the Peruvian state during the 1980s and 1...") |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 04:59, 27 March 2017

The war between the Shining Path and the Peruvian state during the 1980s and 1990s left almost seventy thousand, mostly indigenous, Peruvians dead, and many more bereft, with emotional and physical scars. The legacy of this time of violence could appear entirely bleak, yet recently scholars have examined the opportunities the Shining Path offered traditionally marginalized sectors of the Peruvian population, particularly Peruvian women. Women made up a significant portion of the Shining Path’s membership, and their visibility within the movement was one of its most striking features. Some suggest the Shining Path brought Peruvian women into the public sphere by giving them leadership roles within the revolutionary movement.[1] Other scholars give a more complex analysis of the involvement of women in the Shining Path, finding that both personal agency and exclusionary patriarchy were part of their experience.[2]

The Shining Path failed to generate the significance and power of Peruvian women through their inclusion in the Revolution, nor neutralized their political agency through their co-optation into a patriarchal organization, but rather that the circumstances surrounding the war between the Shining Path and the Peruvian state unleashed the power of women, revealing their profound significance within Peruvian society, and providing them the tools and the space necessary to act politically. An analysis of the Shining Path’s platform, propaganda and membership will demonstrate that the Shining Path was dependent upon women for its empowerment, by showing the instrumental role played by women in legitimizing the image and ideology of the Shining Path. Then, a discussion of the opposition to the violence and terror of the Shining Path will reveal the power of grass-roots organizations led by women. Finally, this paper will show that now, as people study and remember the violence in Peru, women, through their testimonies and interviews continue to shape the legacy of the war, and the image of both the Shining Path, and the Peruvian state.

Foundations of the Shining Path

Several scholars have studied the political, economic, and social context of the rise of the Shining Path, and a brief summary of the conditions in Peru in the late 1960s and 1970s is necessary to understand both the People’s War, and the emergence of women into the public sphere. Poverty and deprivation marked the lives of many Peruvian citizens, especially those who lived in rural, non-Spanish speaking communities. Enrique Mayer writes of the division between “deep”, or indigenous Peru, and “official”, or Hispanic Peru, and describes the ways indigenous Peruvians live with structural violence, the experience of “poverty, abuse, discrimination, racism, and arbitrariness and/or indifference by the state.”[3] Rights for women in Peru were very limited; abortion after rape was illegal, female poverty was on the rise, and women of indigenous background faced virtually insurmountable obstacles.[4]

The “Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces,” led by General Juan Velasco Alvardo came into power in 1968, the year that popular movements and protest erupted in Paris, Mexico City, Prague and other cities worldwide. Velasco enacted educational, agrarian and economic reforms to combat widespread material inequality, and prevent a more radical revolution from the left.[5] Velasco’s top-down reform movement was incomplete, and therefore highly combustive, creating a potent mix of expectation and frustration in a population of increasingly educated and politicized young Peruvians, who were caught at the intersection of reformist promises and structural impediments. [6]

In 1969, a strike of educational workers in Ayacucho revealed the limits of Velasco’s reform and the growing dissatisfaction of teachers and students in Andean communities, what Orin Starn describes as the “climate of sharp unrest across the impoverished countryside.” [7] The activism of members of SUTEP during the 1969 upheaval highlights the collision between the expectations and limitations fostered by the Velasco regime. This was a seminal event for the Shining Path, and used in later publications to contextualize and legitimize the uprising. Shining Path propaganda described the role of women, “In 1969, women heads of households smashed the doors at the Ayacucho food market, after the police closed it during the demonstrations…an elderly woman,…delivered a furious and spontaneous speech to the masses.[8]

The “second “phase” of the reform movement started by Velasco was carried out by his successor, Moralez Burmudez, with a significant movement to the right. Velasco’s agrarian reform led to land take-overs and peasant movements, and according to Floencia Mallon, “if official attempts at popular mobilization and social redistribution seemed to generate a radicalization even more difficult to control, then better to stop Velasco’s ill-fated experiments and once again court the confidence of the investing classes.”[9] Activists, labor leaders, and teachers were fired, repressed, and deported. [9] Promises kept, like expanded education and socialist reform, and promises broken, such as the lack of jobs for indigenous youth, deficient land reform, and the continued repression of social movements, combined to create what Starn calls an “enormous pool of radical young people of amalgamated rural/urban identity who would provide an effective revolutionary force.”[10] Several leftist groups worked within the political and educational space opened up by the Velasco regime, while working against the repressive, inefficient, and indifferent Peruvian state. Other groups, particularly the Shining Path, refused to work within the state-defined system.

Birth of the Shining Path

The Shining Path arose out of the San Cristóbal of Huamanga University in Ayacucho, informed by Maoist/ Leninist/ Marxist ideology, the writings of Mariategui, and the failures of the Peruvian state. The leader of the Shining Path, Abimael Guzman, called President Gonzolo by his followers, sought a protracted people’s war with the state, modeled after the Chinese communist revolution. He led the movement according to ‘Gonzolo Thought’, an ideology that was dedicated to class struggle and combating imperialism, with an emphasis on the importance of the Vanguard Party and the necessity for bloodshed.[11] While other leftist opposition groups attempted to work within the political process, the Shining Path rejected the validity of elections, maintaining connections with few other leftist groups besides SUTEP. The Shining Path continued to work with SUTEP because of the organization’s Maoist ideology and, at least partly, according to Ivan Hinojosa, because, “The education system was the greatest source of cadres for the left.”[12]

On May 17, 1980, the day before Peru held elections for a civilian president after twelve years under a military regime; Shining Path members signaled the beginning of their revolutionary movement by burning ballot boxes in Chuschi, a village in Ayacucho.[13] The Shining Path was not well-known outside the Andean countryside in the at the beginning of the People’s War. The movement was led by white, educated Peruvians, Guzman and his inner-circle who believed the rights of women and indigenous people would be ensured by the dictatorship of the proletariat. Guzman largely dismissed issues of racial and gender equality, yet at the same time, they appealed for ideological legitimacy by recruiting indigenous men and women, and by portraying their movement as a champion of Peruvian women.

A publication from Nueva Bandera from the mid-1990s describes the Marxist approach to gender dynamics, “Women, like men are seen as a combination of social relations, historically formed and changing as a function of the variations in society as it develops. Women are thus a social product and their transformation demands the transformation of society.”[14] They rejected feminist movements that did not share their radical ideology, groups that “preach women’s liberation, simply making some adjustments to this decrepit society.” The article continues to condemn these types of organization, calling them “social cushions” that, “have bourgeoisie and revisionist positions and serve as instruments of oppression and backwardness for women with the aim of pulling them off the path that the proletariat and the people have traversed with the People’s War.”[15] Although the movement lacked space for feminist-oriented activity, it did recognize the tactical significance of women. The women of Peru were necessary to the revolution, according to Lenin, “The Success of the revolution depends on the degree to which the women participate,” and Mao, “Women represent half the population…and they are a force determining the failure or success of the revolution.”[16] Mao and Lenin may have understood importance of women in revolution, but Peruvian women had much more then just demographic strength as half the population.

Women in the Shining Path

Women played an instrumental role in legitimizing the ideology of the Shining Path, as teachers, members, martyrs and propaganda images. By 1990, women made up approximately one-third of the revolutionary group’s membership.[18] Guzman, although aloof from bourgeoisie feminist movements, had formed the Popular Woman’s Movement in 1965, and worked as the director of student teachers in the Education department, where more than half the teachers were women, and according to Robin Kirk, “By 1981 half of Ayacucho’s teachers had received their degrees from the Shining Path-controlled San Cristóbal of Huamanga University (UHSC) Education Department.”[19] In this way, women were involved in the diffusion and reception of the Maoist ideas that underpinned the Shining Path. Women were not only teachers and students of Maoism and Gonzolo Thought, but also members of the movement’s leadership. Guzman’s wife, Augusta was the director of the Popular Women’s movement, but her early visibility waned until a video of her funeral surfaced in 1991.[20] As wife, warrior, or martyr, Augusta was a symbol of the Shining Path’s appeal to Peruvian women and women’s ability to serve in leadership roles. The Shining Path celebrated the image of one young female member very successfully.

In 1982, Edith Lagos, a member of the Shining Path, or Senderista, died at the hands of the police. Earlier that year she had helped mastermind the Ayacucho prison break, and was, according to Robin Kirk, “the most famous Shining Path member after Guzman.” [21] Lagos was misti, or a Peruvian with non-indigenous features, well-educated and the daughter of wealthy parents. Her life an example of the emergence of politicized Peruvian women into the public sphere, and her death an illustration of the power of the image of fierce, dedicated Senderistas. Lagos’ funeral in Huamanga drew ten thousands mourners, who appeared in an amateur video of the event as a “solid carpet of people”.[22] Since her death, Lagos’ grave has been destroyed three times, attesting to the military’s recognition of the power of her martyrdom to inspire Shining Path members and sympathizers. The Shining Path continued to use her as an icon seventeen years after her death, extolling her dedication and martyrdom in a presentation given in San Francisco by a member of the Committee to Support Revolution in Peru at a gathering on International Women’s Day called “Women Hold up Half the Sky, The Role of Women in the Revolution in Peru.”[23]

The Shining Path appealed to women within Andean communities, building its membership and ideological legitimacy. They did this by holding trials of wife-beaters, adulterers, and rapists.[24] Later publications of Shining Path propaganda recount their role proudly, “Peru’s traditional Andean peasant culture is quite a lot more rigid than prevailing in the urban areas. Peasant women who would stray from their husbands are severely punished but sexual harassment and adultery on the part of men is rather prevalent. On the other hand, where the Party established its influence, divorce is introduced and sexual harassment is not tolerated.”[25] Previously “invisible,” in the words of Isabel Coral Cordero, and trapped within a system that recognized only their domestic contributions, the Shining Path gave Peruvian women education, social justice, and opportunities to act alongside men in the People’s War.

Yet at the same time, gender issues were not part of the Shining Path’s platform, only their rhetoric. Guzman, like the primary influences in his life, Marx, Lenin, Mao and Mariategui, found gender insignificant in comparison to class struggle, but recognized the necessity of women’s involvement in the Revolution. “Only the direct and massive participation of revolutionary women, principally working women,” Guzman is quoted as saying “…in the (the revolution) remains the sole guarantee of genuine defense and promotion of women’s rights within a real and concrete path of liberation.”[26] The Shining Path recognized the need for women in the movement, yet it cannot be said that they offered Peruvian women emancipation or political agency, only that they sought their support through policies and rhetoric that validated their significance within Peruvian society and the revolution.

In contrast to the image of invisibility, domesticity, and sacrifice of Peruvian women described above, the figure of the female Senderista fighter inspired fear. The perception of these women warriors often had racial and gendered implications, harkening back to both stories of fierce Andean females, and the teachings of Mariategui. Mariategui described the nature of women as, “Lack[ing] a sense of justice. Women’s flaw is to be too indulgent or too severe. And they, like cats, have a mischievous inclination for cruelty.”[27] Robin Kirk conducted interviews and research on the role of women in the Shining Path and found two prevailing perceptions of the “crazy” women drawn to join the People’s war, either “sexless automatons,” or “bloodthirsty nymphomaniacs.” Kirk writes that “It was as if Nature had delivered a totally new creature…it frightened and gave Guerillas an aura of unnatural, witchy power,” and quotes her cabdriver’s sentiment that “women from the mountains were, strong-willed, warlike.”[28] Senderistas were rumored to regularly deliver the ‘coup de grace’ in targeted assassinations and popular trials, further building their image as cold and deadly.[29] The Shining Path reinforced this racialized perception of Andean women in its literature, quoting a 1923 El Tiempo newspaper article that described Andean women’s “rich history” of involvement in rebellions in the Ancco and Chusqui districts, saying, “They mistreated the mayor and the chief tax collectors of theses districts in a cruel and inhumane way, and left them fatally wounded.”[30] The Shining Path did not create this image of strong, dangerous Peruvian women, they merely applied it in order to legitimize their appeal to indigenous communities, using both fear of women’s innate cruelty, and pride in Andean resistance and independence.- ↑ Carol Andreas, “Women at War,” NACLA Report on the Americas, 24, no 4, (Dec/Jan 1990-1991), 21-25.

- ↑ Robin Kirk, The Monkey’s Paw: New Chronicles from Peru, (Amherst: University of Massechusetts Press, 1997), 64; Isabel Coral Corder, “Women in War,” Shining and Other Paths: War and Society in Peru, 1980-1995, ed Steve Stern, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), 352.

- ↑ Enrique Mayer, “Peru in Deep Trouble,” Rereading Cultural Anthropology, ed. George E. Marcus, (Durhm: Duke University Press, 1992), 188-193.

- ↑ Kirk, The Monkey’s Paw, 78-80.

- ↑ Orin Starn, Carlos DeGregori, and Robin Kirk. The Peru Reader: History, Culture, Politics, ed. Orin Starn, carlos Ivan Degregori, and Robin Kirk, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995), 264.

- ↑ Starn, DeGregori, and Kirk. The Peru Reader 264.

- ↑ Orin Starn, “Missing the Revolution, Anthropologists and the People’s War in Peru,” Rereading Cultural Anthropology. 153; Ivan Hinojosa, “On Poor relations and the Nouveau Riche: Shining Path and the Radical Peruvian Left,” Shining and Other Paths, 70.

- ↑ The New Flag Magazine, “How Women Advance the Revolution,” (1998), 1-2.

- ↑ Hinojosa, “On Poor Relations,” 70-71.

- ↑ Orin Starn, “Missing the Revolution, Anthropologists and the People’s War in Peru,” Rereading Cultural Anthropology. 153

- ↑ Orin Starn , “Maoism in the Andes: Shining Path,” 291; Carlos Ivan, and Kirk, The Peru Reader, 306.

- ↑ Ivan Hinojosa, “On Poor relations and the Nouveau Riche: Shining Path and the Radical Peruvian Left,” Shining and Other Paths, 71.

- ↑ Starn, Ivan, and Kirk, The Peru Reader, 305.

- ↑ “Marxism and the Emacipation of Women,” Nueva Bandera, 1,3 (September/October 1994), 21.

- ↑ “Marxism and the Emacipation of Women,” 20.

- ↑ Committee to Support the Revolution in Peru (CSRP), “The Other Half of the Sky,” Committee Sol Peru, (August 1997), 1.