Difference between revisions of "What was the impact of John Knox, on Scotland and on religion"

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

Without Knox and his defiance of Mary Queen of Scots, the kingdom could have reverted to Catholicism. His singular bravery ensured that ultimately Scotland was to remain a Protestant state. This, in turn, was to draw Edinburgh away from its old alliance with France. Over time this led to a growing alliance between Scotland and England and ultimately the union of the two realms in the person of James I, a union that has persisted to the present day. | Without Knox and his defiance of Mary Queen of Scots, the kingdom could have reverted to Catholicism. His singular bravery ensured that ultimately Scotland was to remain a Protestant state. This, in turn, was to draw Edinburgh away from its old alliance with France. Over time this led to a growing alliance between Scotland and England and ultimately the union of the two realms in the person of James I, a union that has persisted to the present day. | ||

| − | <div class="portal" style='float: | + | <div class="portal" style='float:left; width:35%'> |

====Related Articles==== | ====Related Articles==== | ||

| − | {{#dpl:category=Religious History|ordermethod=firstedit|order=descending|count= | + | {{#dpl:category=Religious History|ordermethod=firstedit|order=descending|count=10}} |

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 02:27, 23 September 2021

John Knox was a Scottish cleric, (1513-1572), who died in poverty and was largely forgotten. However, he was one of the most important figures in the history of Scotland and he changed that nation and his influence is still felt to this day. He was the leader of the Scottish Reformation and an influential theologian.

Knox was also very important in the politics of the time and he played a pivotal role in the political evolution of Scotland and the British Isles. This article will argue that John Knox overthrew Catholicism in Scotland, helped to establish Presbyterianism, paved the way for the unification of Scotland and England and the emergence of the United Kingdom.

Why was Scotland divided between Catholics and Protestants?

Scotland was a poor country and it was constantly at odds with its larger neighbor to the south, England. The Scottish kings were little more than the vassals of the king of England, especially after the disastrous Scottish defeat at the Battle of Flodden. Scotland was closely allied with the French monarchy, in a bid to preserve her independence. The Scottish kingdom was often torn between the demands of England and France. The nobles of Scotland, especially after Flodden were very restive and often acted as independent rulers, especially those in the Highlands and Islands.[1]

The Scottish monarch was usually weak and dependent on their nobles and indeed often their tools. The religious situation in Scotland in the first half of the sixteenth century was very tense. The Catholic Church was corrupt and in need of reform. Many Scottish nobles and townspeople wanted to introduce Protestantism. However, France was influential, and the Court of the monarch was usually Catholic. In the Highlands of Scotland, the Gaelic speaking population was decidedly Catholic. Religion became intertwined in the traditional and never-ending struggle between the nobles and the monarch.

The French supported the Catholic factions and the English supported those who were sympathetic to the Reformation. In 1542, the Scots were once again defeated by the English at Solway Firth. James V of Scotland died soon after this and his young daughter Mary was his heir. Real power lay with the Catholic faction led by Cardinal Beaton and the French Queen Mother Catherine of Guise. In 1546, Cardinal Beaton was assassinated and this was an important point in the Scottish Reformation. After this time, the Protestant nobility began to become more influential in Scotland. After Mary Queen of Scots ascended the throne, there was an effort to reverse the Scottish Reformation. However, she was deposed, and this led to the final triumph of Protestantism in Scotland.[2]

Who was John Knox?

John Knox was born in Giffordgate, Scotland, around 1513. His father was a rather unsuccessful merchant. Knox is believed to have been educated at the University of St. Andrews and worked as a notary-priest. At an early date, he was influenced by the early Scottish church reformers such as George Wishart, who was later executed as a heretic. His experience as a cleric had persuaded him that the church in Scotland had to be reformed. Soon, because of the force of his personality and his fiery sermons Knox became one of the leaders of the reform movement.[3] Knox was caught up in the ecclesiastical and political events that involved the murder of Cardinal David Beaton in 1546. He was not a party to the assassination of the Cardinal.

In 1547, a French expeditionary force landed in Edinburgh and they ensured that a pro-French faction secured the government of the kingdom. Scotland Mary of Guise, a French noblewoman, became the regent to the future Mary Queen of Scots. Knox was taken prisoner by French forces. For over a year, he was forced to serve as a galley slave and he almost died because of his terrible treatment. He was eventually released and exiled to England in 1549. The Scot was licensed to work in the Church of England, because of his Protestant credentials. He became the Royal Chaplin to King Edward VI. He exerted a reforming influence on the text of the Book of Common Prayer. When Mary I (Bloody Mary) ascended the throne of England and re-established Roman Catholicism, Knox was forced to flee once more. Knox moved to Geneva and where he met John Calvin. Calvin provided him with knowledge about Reformed theology and Presbyterian polity.[4] Calvin changed Knox’s view of religion and greatly influenced his theological thinking. The encounter between Calvin and Knox was crucial in the development of the Presbyterian Church.

Why did John Knox call for Mary, Queen of Scots, Execution?

Later, Knox broke with the Church of England and Anglicanism. The reformer returned to Scotland and by now he was one of the leaders of the Scottish Reformation and in 1560 he helped to establish the Church of Scotland. He formed an alliance with the Scottish Protestant nobility and he openly challenged Mary Queen of Scots and denounced her attempts to restore Catholicism.[5] When the Queen was imprisoned for her alleged role in the murder of her husband Lord Darnley, he openly called for her execution. The reformer continued to preach until his final days and remained one of the leaders of the Reformation in Scotland.[6]

What was John Knox's role in the Scottish Reformation?

Knox firmly believed he was on a divine mission to reform the church in Scotland. The reformer’s philosophy was that ‘a man with God was always in the majority.’[7] Knox did not believe that he was an innovator but that he was restoring the Church. The power of his preaching and his writings did much to spread the Reformed faith in Scotland. In 1560 he played a key role in the establishment of the Church of Scotland, and the end of Papal jurisdiction in the kingdom.

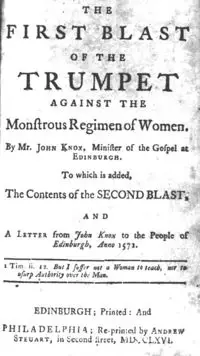

Knox was a decisive influence on the Church of Scotland and he gave it, its distinctive character. He created a new order of service, which was eventually adopted by the reformed church in Scotland. Knox helped write the new confession of faith and the ecclesiastical order for the newly created church, known colloquially as the Kirk. The Kirk was to be the most important social-religious institution in Scotland for many centuries. This was a congregation of elders and bishops who were entrusted with the government of the Church and with enforcing Christian teachings and morals in society. Knox published the First Book of Discipline, which set out the duties of clerics and enabled the transfer of property from the old Church to the new entity.[8]

Under Knox, priests became ministers, bishops served as superintendents and new structures were put in place. Know did not believe that he was creating a new Church but that he was rather reforming it. In reality, he had changed the church beyond recognition and had transformed it. It was not until 1592 that a full Presbyterian system was adopted by the Scottish Church and Parliament. This was composed of courts made up of ministers and elders.

John Knox and Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary Queen of Scots was a committed Catholic and like her namesake Mary, I of England tried to restore Catholicism. As the monarch, she was the divinely anointed ruler of the kingdom. Her support for Catholicism was a real threat to the continued growth of Protestantism in the realm. By this date, the Church in Scotland was ‘reformed’ and Mary was its head. However, the Queen was openly sympathetic to the Papacy and openly held mass at her castle, which was contrary to the laws of the land. Knox publicly denounced her and her Catholic faith. In a series of interviews, Mary tried to intimidate Knox and persuade him that she as Queen could practice her faith and that she was not a threat to the Church of Scotland.

Knox was one of Mary’s chief critics during the controversy over the assassination of her husband, Lord Darnley.[9] He openly denounced the queen when she married the chief suspect the notorious Earl of Boothby. Knox continued to rouse the opposition to Mary and he helped to persuade the Protestant nobles to depose Mary and placed her son, James on the throne. This they eventually did, and Knox was granted the honor of preaching a sermon at the coronation of James, who became James VI of Scotland. [10] With the accession of James, the Reformation in Scotland was secure, and Catholicism was marginalized and confined to the remote Highlands and Islands.

How did John Knox advance the development of Presbyterianism?

The Scottish reformer decisively shaped the form of the Reformation in the kingdom. Prior to his meeting with Calvin, he was an adherent of the Anglican Church and influenced by its forms of Church governance and theology. He was much influenced by what he saw in Geneva where Calvin had reformed the Church and the City-State. The Scot did not imitate Calvin, but he was deeply impressed by what he saw.[11] Knox adopted the ideas of Calvin with regard to the Presbyterian form of church government, which is governed by representative assemblies of elders. He believed that this would not only reform the Church but to ensure that people conformed to the teaching of the scriptures.

Knox's interpretation of Calvin was crucial in the development of Presbyterianism and its theology.[12] He helped to transmit the ideas of Calvin on the Church government to Scotland and England. Indeed, the Scottish Reformer was a pivotal influence on the development of English Puritanism. The Scottish Presbyterian Church was spread by migrating Scots to Northern Ireland, America, and Canada and from here it spread all over the globe. None of this would have been possible without the ideas of John Knox. Even though he did not want to establish a new Church he can be regarded as one of the founders of the Presbyterian Churches around the world.

Knox and Scotland in Europe

Traditionally, Scotland had been trenchantly anti-English, and to counter its larger neighbor it had formed a long-lasting alliance with France. Typically, when France and England were at war, the Scots would invade Northern England. This was the pattern of events until the Knox inspired Scottish Reformation. Knox and the Protestant nobles came to believe that England which was a Protestant kingdom was not its enemy. Rather the real enemy was Catholic France, which was the champion of the corrupt Papacy and corrupt clergy. The Scottish Reformation changed how many Scots perceived their relationship with England. Knox and those who were sympathetic to the Reformation came to see England as an ally and France as an enemy.

The outcome of this was that under James VI of Scotland that there was a rapprochement between Edinburgh and London. The two realms as Protestant kingdoms believed that they had a common foe in Catholic Spain and France.[13] There were to be no further wars between Scotland and England during the reign of James VI. When Elizabeth I died, her powerful minister Cecil was able to engineer the accession of James VI of Scotland as James I of England in 1603. This led to the unification of the crowns of England and Scotland and this was to ultimately lay the foundation for the establishment of the United Kingdom in 1707. The dramatic change in the relationship between Scotland and England was in no small measure a result of John Knox, who was a key figure in the success of the Scottish Reformation.

Conclusion

John Knox was a giant of Scottish history and indeed in the history of the Reformation. He was a key reason for the success of the Scottish Reformation and in the development of the Church of Scotland. He was also significant in that he ensured that the Church was influenced by Calvinism in its governance and theology. Knox’s encounter with Calvin was ultimately the origin of the Presbyterian Church, which is a worldwide movement.

Without Knox and his defiance of Mary Queen of Scots, the kingdom could have reverted to Catholicism. His singular bravery ensured that ultimately Scotland was to remain a Protestant state. This, in turn, was to draw Edinburgh away from its old alliance with France. Over time this led to a growing alliance between Scotland and England and ultimately the union of the two realms in the person of James I, a union that has persisted to the present day.

Related Articles

- How Did the God Baal Become Popular

- How Did the Ancient Egyptian City of Thebes Become Prominent

- How Did the Ancient City of Sais Rise to Prominence

- Why Did Seth Worship Become Popular in Ancient Egypt

- What Were Some of the Influences on Hittite Religion

- How did the Second Great Awakening change the United States

- What is the history of how gods ruled over humanity

- What is the history of apocalyptic mythologies

- What is the history of creation mythologies

- What happened to the ark of the covenant

References

- ↑ Devine, T. M., The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London, Penguin Books, 1999, p. 118)

- ↑ Devine, p. 201

- ↑ Dawson, Jane, John Knox, (London: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 13

- ↑ Dawson, p. 198

- ↑ Devine, p. 201

- ↑ Dawson, p. 167

- ↑ Dawson, p. 189

- ↑ Laing, David, ed., The Works of John Knox (Edinburgh: James Thin, 55 South Bridge, 1895), p. 179

- ↑ Warnicke, Retha. M, Mary Queen of Scots, (New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 134

- ↑ Warnicke, p. 119

- ↑ Kyle, Richard G., "John Knox: The Main Themes of His Thought", Princeton Seminary Bulletin 4, no. 2 (1983): 112

- ↑ Dawson, p. 119

- ↑ Devine,p. 245