Difference between revisions of "What Were Some of the Influences on Hittite Religion"

(Created page with "300px|thumbnail|left|Relief in Hattusa of the Hurrian-Hittite God, Teshub As with all pre-modern peoples, religion was very important to the ancie...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[File: Hattusa_Teshub.jpg| | + | [[File: Hattusa_Teshub.jpg|250px|thumbnail|left|Relief in Hattusa of the Hurrian-Hittite God, Teshub]]__NOTOC__ |

As with all pre-modern peoples, religion was very important to the ancient Hittites because it was a crucial component to how they viewed the world and was central to the role kingship played in their society. Unlike the modern secular world, religion permeated all aspects of life in the ancient world and was intertwined with politics, government, and even commerce. Unfortunately, although there are many extant Hittite religious texts, they do not present a cohesive pictures of the entire religion: many focus more on the ritual aspects of the religion and the mythological texts are incomplete. With that said, a number of conclusions can be drawn from those texts about the nature of Hittite religion, namely its influences. | As with all pre-modern peoples, religion was very important to the ancient Hittites because it was a crucial component to how they viewed the world and was central to the role kingship played in their society. Unlike the modern secular world, religion permeated all aspects of life in the ancient world and was intertwined with politics, government, and even commerce. Unfortunately, although there are many extant Hittite religious texts, they do not present a cohesive pictures of the entire religion: many focus more on the ritual aspects of the religion and the mythological texts are incomplete. With that said, a number of conclusions can be drawn from those texts about the nature of Hittite religion, namely its influences. | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

===Religion in the Bronze Age Near East=== | ===Religion in the Bronze Age Near East=== | ||

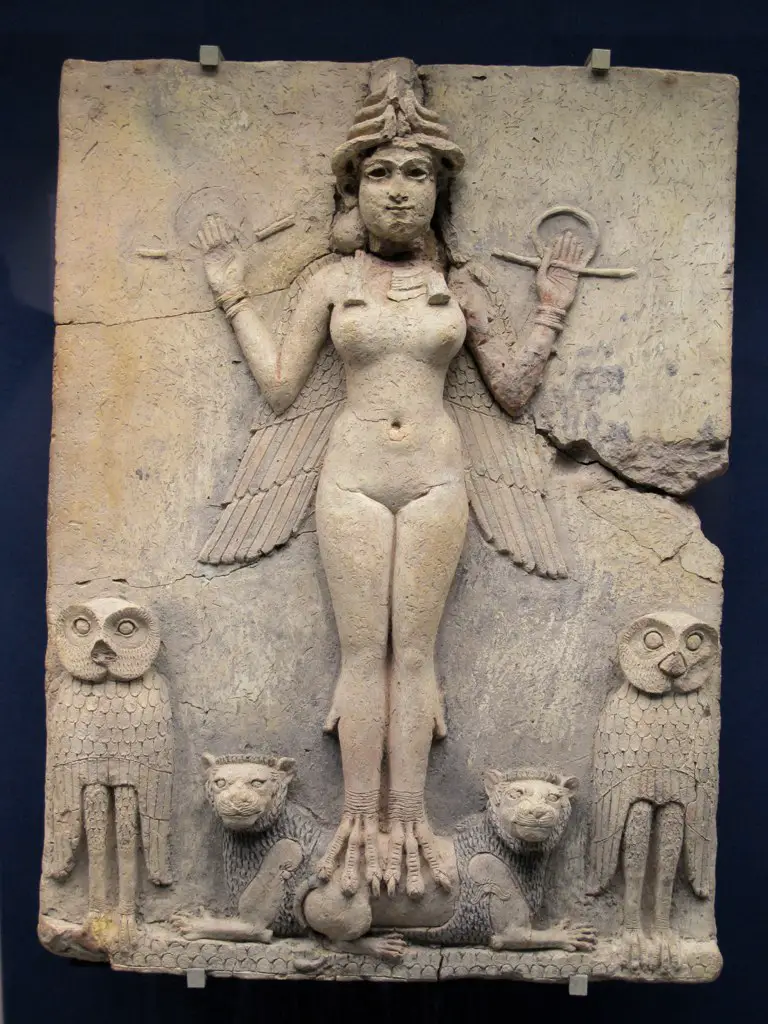

| − | [[File: Ishtar.jpg| | + | [[File: Ishtar.jpg|2500px|thumbnail|left|Statue of the Semitic Goddess of Love and War, Ishtar]] |

The Bronze Age Near East (c. 3000-1200 BC) had several different religious traditions, but the three most important came from Mesopotamia, the Levant (Syria-Palestine), and Egypt. The religion of these cultures was not dogmatic and would often spread peacefully through trade to other regions, leading to the syncretic fusion of deities and ideas. Although this syncretism was not at the level witnessed in classical antiquity, it was apparent in some places, especially during the Late Bronze Age (c. 1,500-1,200 BC). | The Bronze Age Near East (c. 3000-1200 BC) had several different religious traditions, but the three most important came from Mesopotamia, the Levant (Syria-Palestine), and Egypt. The religion of these cultures was not dogmatic and would often spread peacefully through trade to other regions, leading to the syncretic fusion of deities and ideas. Although this syncretism was not at the level witnessed in classical antiquity, it was apparent in some places, especially during the Late Bronze Age (c. 1,500-1,200 BC). | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

===The Hittite Gods and Goddesses=== | ===The Hittite Gods and Goddesses=== | ||

| − | [[File: King’s_Gate.jpg| | + | [[File: King’s_Gate.jpg|250px|thumbnail|left|Relief in Hattusa of a Warrior on the King’s Gate in Hattusa]] |

In order to understand the Hittite’s diverse religious influences, one should begin with their most important god – the “Storm-God.” As the name indicates, the Hittite Storm-God was an elemental god who controlled the weather and the winds. He was never given a specific name, but instead would be referred to be a specific locality: the “Storm-God of Hattusa” or the “Storm-God of Nerik,” for instance. Among all of the Hittite deities, the Storm-God was primarily an Indo-European god. <ref> Beckman, Gary. “The Religion of the Hittites.” <i>Biblical Archaeologist</i> 52 (1989) p. 99</ref> Similar to the Aryan Indra, the Greek Zeus, and the Norse Thor, the Hittite Storm-God had control over the elements and could use them constructively or destructively, depending upon the situation. Although the Storm-God clearly had Indo-European origins, his later worship was influenced by the Hurrians. | In order to understand the Hittite’s diverse religious influences, one should begin with their most important god – the “Storm-God.” As the name indicates, the Hittite Storm-God was an elemental god who controlled the weather and the winds. He was never given a specific name, but instead would be referred to be a specific locality: the “Storm-God of Hattusa” or the “Storm-God of Nerik,” for instance. Among all of the Hittite deities, the Storm-God was primarily an Indo-European god. <ref> Beckman, Gary. “The Religion of the Hittites.” <i>Biblical Archaeologist</i> 52 (1989) p. 99</ref> Similar to the Aryan Indra, the Greek Zeus, and the Norse Thor, the Hittite Storm-God had control over the elements and could use them constructively or destructively, depending upon the situation. Although the Storm-God clearly had Indo-European origins, his later worship was influenced by the Hurrians. | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

===References=== | ===References=== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

[[Category: Myths and Gods]] [[Category: Ancient History]] [[Category: Bronze Age History]] [[Category: Ancient Anatolian History]] [[Category: Religious History]] | [[Category: Myths and Gods]] [[Category: Ancient History]] [[Category: Bronze Age History]] [[Category: Ancient Anatolian History]] [[Category: Religious History]] | ||

| + | {{Contributors}} | ||

Revision as of 22:42, 21 September 2021

As with all pre-modern peoples, religion was very important to the ancient Hittites because it was a crucial component to how they viewed the world and was central to the role kingship played in their society. Unlike the modern secular world, religion permeated all aspects of life in the ancient world and was intertwined with politics, government, and even commerce. Unfortunately, although there are many extant Hittite religious texts, they do not present a cohesive pictures of the entire religion: many focus more on the ritual aspects of the religion and the mythological texts are incomplete. With that said, a number of conclusions can be drawn from those texts about the nature of Hittite religion, namely its influences.

What is immediately clear to anyone who makes even a cursory study of Hittite religion is how syncretic it was. Although nearly all of the cultural groups of the ancient Near East borrowed cultural attributes from each other, including religion, the Hittites did so more than others. The Hittites were one of three Indo-European groups that entered Anatolia in the third millennium BC, bringing not only their language with them, but also their religion. But not long after the Hittites established their hegemony over central Anatolia, other ethnic influences entered their religion, including: Hattic (native Anatolian), Hurrian, and Semitic.

Religion in the Bronze Age Near East

The Bronze Age Near East (c. 3000-1200 BC) had several different religious traditions, but the three most important came from Mesopotamia, the Levant (Syria-Palestine), and Egypt. The religion of these cultures was not dogmatic and would often spread peacefully through trade to other regions, leading to the syncretic fusion of deities and ideas. Although this syncretism was not at the level witnessed in classical antiquity, it was apparent in some places, especially during the Late Bronze Age (c. 1,500-1,200 BC).

The Late Bronze Age Near East saw the creation of the first true geo-political system, known by modern scholars as the “Great Powers Club.” The Great Powers included Egypt, Hatti (Hittites), Babylon, Alashiya (Cyprus), and later Assyria. The smaller Canaanite states were “lesser powers,” and there were also larger states such as Elam and the Myceneans located on the periphery of the region that although not directly involved in the system, were in contact with one or more of the Great Powers members. The Great Powers went to war against each other, although usually not directly, exchanged diplomats, and engaged in long-distance trade with each other. [1]As the powers traded material goods, they also traded religious ideas.

The spread of religious ideas in the Near East actually began in the Early Bronze Age with the Sumerians and the Gilgamesh Epic. According to the epic, Gilgamesh was a legendary king of the Sumerian city of Uruk, but long after Sumerian influence in Mesopotamia evaporated, other peoples copied the story. The Gilgamesh Epic was copied in Akkadian and even later in Hittite. [2] As the Gilgamesh Epic made its way throughout the ancient Near East, so too did different deities.

Perhaps the most important, or at least most popular, ancient Near Eastern deity was Inanna. Inanna was originally the Sumerian goddess of love and war, but later Semitic Mesopotamian peoples adopted the goddess as Ishtar, and as her popularity grew she became part of the Hittite pantheon and the Canaanite pantheon as Astarte. There are numerous extant records of Astarte being worshipped throughout the Levant; the Old Testament book I Samuel 31 mentions how the Philistines worshiped her. During the Late Bronze Age, Astarte made her way into Egypt where she became quite popular in the Delta, being viewed as the daughter of Re or Ptah and the consort of Seth. [3]

The Hittite Gods and Goddesses

In order to understand the Hittite’s diverse religious influences, one should begin with their most important god – the “Storm-God.” As the name indicates, the Hittite Storm-God was an elemental god who controlled the weather and the winds. He was never given a specific name, but instead would be referred to be a specific locality: the “Storm-God of Hattusa” or the “Storm-God of Nerik,” for instance. Among all of the Hittite deities, the Storm-God was primarily an Indo-European god. [4] Similar to the Aryan Indra, the Greek Zeus, and the Norse Thor, the Hittite Storm-God had control over the elements and could use them constructively or destructively, depending upon the situation. Although the Storm-God clearly had Indo-European origins, his later worship was influenced by the Hurrians.

The Hurrians were a Caucasian linguistic-ethnic group that lived in the Near East from at least about the time the Hittites entered Anatolia. [5] The Hurrians established several small kingdoms in Syria in the late third millennium BC and later comprised the ethnic majority of the Hittites’ major rival, the Mitanni Kingdom (1500s-1300s BC). Although the Hurrians and Hittites clashed, they also developed some cultural affinities, especially in religion. For instance, the Hurrians also had a storm-god, whom they named Teshub. By the late thirteenth century BC, as the Hittites became more firmly involved in the Great Powers system, Hittite texts began referring to the Storm-God as Teshub. [6]

The Hittite Storm-God’s consort, the Sun-Goddess, was equally important and even eclipsed the Storm-God late in Hittite history. The Sun-Goddess is believed to have been derived from the native Anatolian Hattic people as a mother goddess, but not long after the Hittites entered Anatolia they adopted her, and due to her elemental associations they began associating her with their Storm-God. As with the Storm-God, the Sun-Goddess was not named until the Hurrian influence on Hittite religion became more pronounced in the thirteenth century, at which time she became known by the Hurrian name, Hebat. [7] The Sun-Goddess was perhaps the most influential and longest lived deities of the Hittite pantheon, being worshipped by the later Phrygians and Lydians and eventually evolving into the well-known goddess Cybele during the Greco-Roman Period. [8]

In addition to the Storm-God and the Sun-Goddess, the Hittites worshipped a number of deities associated with geographic locations, elements, and concepts. Taru was a popular god associated with water and Wurunkatte was a war god, who was especially important to the bellicose and expansionistic Hittites. Both of Taru and Wurnkatte were Hattic in origin. [9] Although the Hittites lacked in native cosmological myths compared to the people of Mesopotamia, one of their myths perfectly encapsulates the wide range of influences on their religion. In this particular myth, the Storm-God has sex with the Canaanite god, El’s wife. After the Storm-God reveals that he killed several of El’s children, El and his wife conspire to kill him, only to have the Semitic goddess Ishtar intervene on the Storm-God’s behalf.

“El-kunirsha beheld the Storm-god and asked him: ‘[Why] didst thou come?’ Thus said the Storm-god: When I entered thy house, Ashertu sent out (her) maidens to me (saying).’ Come sleep with me!’ ‘[When] I refused, she became aggressive . . . Although she is thy wife she keeps on sending to me:’ ‘Come, sleep with me.’ El-kunirsha began to reply to the Storm-go: ‘Go, sleep with her! Lie with my wife and humble her!’ The Storm-god hearkened to the world of El-kunirsha. With Asertu he slept. The Storm-god said to Ashertu: ‘Of thy sons I slew 77, I slew 88.’ Ashertu heard this humiliating word of the Storm-god and her mind got incensed against him. . . [When El-kunrisha] heard these words, he said to his wife: ‘[. . .] the Storm-god, I shall turn him over to thee. As thou pleases, thus d[eal] with him!’ Ishtar heard those words. In El-kunirsha’s hand she became a cup. . . But Ishtar flew like a bird across the . . . and found the Storm-god.” [10]

Conclusion

The people of the Bronze Age Near East practiced various religions that although different in form, were never in direct conflict with each other. Although wars were not uncommon in the Bronze Age Near East, religion was never a cause and in fact religious ideas, myths, and even deities made their way from one culture to another. Among all the Bronze Age Near Eastern religions, the Hittite is perhaps the best example of this religious diffusion. The Indo-European Hittites practiced a religion that placed one of their gods at the forefront, but with plenty of native Anatolian, Semitic, and Hurrian deities and influences in supporting and later, leading roles.

References

- ↑ Mieroop, Marc van de. A History of the Ancient Near East: ca. 3000-323 BC. Second Edition. (London: Blackwell, 2007), pgs. 129-148

- ↑ Snell, Daniel C. Religions of the Ancient Near East. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 88

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), pgs. 138-9

- ↑ Beckman, Gary. “The Religion of the Hittites.” Biblical Archaeologist 52 (1989) p. 99

- ↑ Kuhrt, Amélie. The Ancient Near East: c. 3000-330 BC. (London: Routledge, 2010), pgs. 288

- ↑ Macqueen, J. G. The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor. Second Edition. (London: Blackwell, 2007), p. 111

- ↑ Macqueen, p.111

- ↑ Beckman, p. 99

- ↑ Macqueen, p. 110

- ↑ Pritchard, James B, ed. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Third Edition. (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1992), p. 519

Admin and Jaredkrebsbach