Difference between revisions of "Was Merlin based on a real person"

m (Admin moved page Was Merlin based on a real person? to Was Merlin based on a real person) |

|||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

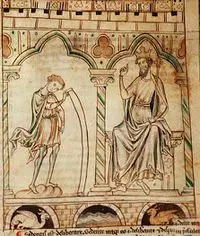

[[File: Merlin One.jpg|200px|thumb|left| A medieval manuscript with a drawing of Merlin and King Arthur]]__NOTOC__ | [[File: Merlin One.jpg|200px|thumb|left| A medieval manuscript with a drawing of Merlin and King Arthur]]__NOTOC__ | ||

| − | Merlin is perhaps the best-known wizard or magician in popular culture. He is one of the key characters in the much-loved Arthurian legends. In these stories, he is the court magician and mentor of the ruler of Camelot. Since the Middle Ages, Merlin has become a by-word for the practice of magic. He has been portrayed countless times | + | Merlin is perhaps the best-known wizard or magician in popular culture. He is one of the key characters in the much-loved Arthurian legends. In these stories, he is the court magician and mentor of the ruler of Camelot. Since the Middle Ages, Merlin has become a by-word for the practice of magic. He has been portrayed countless times in books, plays, and movies. However, was Merlin based on a real-life character? This article will discuss if he was based on an actual historical figure or merely a fictional character, the product of medieval writers and poets. It will discuss possible candidates for the original Merlin, and these include a Scottish prophet, an early British king, and the theory that he was a Celtic priest, a druid. |

====The context of the story of Merlin==== | ====The context of the story of Merlin==== | ||

[[File: Merlin Two.jpg|200px|thumb|left|A 19th century print showing Merlin as a druid]] | [[File: Merlin Two.jpg|200px|thumb|left|A 19th century print showing Merlin as a druid]] | ||

| − | The Arthurian Cycle of stories and | + | The Arthurian Cycle of stories and Merlin's legend is based on more or less historical events that occurred in the wake of the collapse of Roman power in the West. In 410 AD, the last Roman legion left Britain, and the natives had to fend for themselves. Several small Brythonic kingdoms were faced with an invasion by pagan Saxons and other Germanic tribes. This was an era when great warlords emerged, such as Vortigern, who fought against the barbarians. This is when legendary warrior-kings, such as Uther Pendragon and Arthur, were said to rule. |

| − | The Brythonic kingdoms were all Christian, but they were also Roman-Celtic. They were pushed out of | + | The Brythonic kingdoms were all Christian, but they were also Roman-Celtic. They were pushed out of England's rich lowlands into the highlands of Cornwall, Wales, and Scotland. At this time, popularly known as the Dark Ages, many pre-Christian practices remained, and much of the population was still half-pagan. There were still old-style magicians and prophets, who were believed to have special powers, such as those possessed by Merlin, even by clerics and monks <ref> Tolstoy, Nikolai. The Quest for Merlin (London, H. Hamilton, 1985), p 14</ref>. |

====The sources of Merlin==== | ====The sources of Merlin==== | ||

| − | There is no one fixed version of the story of Merlin. He is first mentioned in the ''History of the Kings of Britain'' by Geoffrey de Monmouth. The same author then wrote a book | + | There is no one fixed version of the story of Merlin. He is first mentioned in the ''History of the Kings of Britain'' by Geoffrey de Monmouth. The same author then wrote a book that purports to be Merlin's prophecies (1130 AD). In these prophecies, well-known historical figures were represented by animals and their futures told in riddles. Monmouth claims that the prophecies and the figure of Merlin are based on ancient oral sources. He shows Merlin to be a key member of King Arthur’s inner circle. |

| − | In his later work, the Vita Merlini, he elaborated on the story of | + | In his later work, the Vita Merlini, he elaborated on the story of Camelot's wizard. Many have accused Geoffrey of Monmouth of simply inventing the famous wizard and prophet. In the 13th century, a French poet, Robert de Boron, wrote an epic poem on the magician based on Monmouth's work. Some of this work is lost, but it was very influential in the popularity of Merlin's character.<ref> Jankulak, Karen. Geoffrey of Monmouth (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2010), p. 11</ref> In later centuries, Thomas Mallory and other writers greatly elaborated on the wizard's story. They did not emphasize his powers of prophecy but concentrated on his supernatural powers. |

====The life and adventures of Merlin==== | ====The life and adventures of Merlin==== | ||

[[File: Merlin Three.png|200px|thumb|left|A 19th century print showing Merlin as a druid]] | [[File: Merlin Three.png|200px|thumb|left|A 19th century print showing Merlin as a druid]] | ||

| − | According to most sources, Merlin was the son of an incubus or a preternatural being, often viewed as demonic. He may have been the son of a Royal Princess, from the north of England. He was baptized as a Christian and this purified him, but he was a paradoxical figure, good, but also tainted by his demonic inheritance. | + | According to most sources, Merlin was the son of an incubus or a preternatural being, often viewed as demonic. He may have been the son of a Royal Princess, from the north of England. He was baptized as a Christian, and this purified him, but he was a paradoxical figure, good, but also tainted by his demonic inheritance. |

| − | Merlin was a powerful prophet and magician from an early age and is shown as helping a Brythonic ruler to defeat the Anglo-Saxon invaders | + | Merlin was a powerful prophet and magician from an early age and is shown as helping a Brythonic ruler to defeat the Anglo-Saxon invaders while still a teenager. He was often shown to be also a shapeshifter, who is at once an older man, a handsome youth, and even a deer. One of his most famous feats was to build Stonehenge by transporting stones from Ireland. He is a key figure in the Arthurian legends and is shown as an advisor to King Arthur’s father, Uther Pendragon. He helped Uther to disguise himself and to impregnate the wife of his enemy. From this act, the future King Arthur was born. Merlin is a critical figure in the ‘Story of the Sword.’ He predicts that the man who takes the sword from the stone (or anvil in some accounts) is the rightful monarch of Britain. Merlin is typically shown to be the mentor and teacher of Arthur. It is he who helps him to become King of the Britons. |

| − | In one version, offered by Geoffrey de Monmouth, the wizard married a beautiful woman and retired to study the stars. However, in another version, Merlin becomes Arthur’s advisor and his court magician.<ref>Tolstoy, p. 119</ref> Some stories | + | In one version, offered by Geoffrey de Monmouth, the wizard married a beautiful woman and retired to study the stars. However, in another version, Merlin becomes Arthur’s advisor and his court magician.<ref>Tolstoy, p. 119</ref> Some stories clarify that Merlin was partly responsible for Arthurs victories. He is also shown as helping him to gather enough knights for the fabled Round Table. In some French accounts, the wizard is a significant figure in the Holy Grail and the Knights of the Round Tables quest for the chalice that held Christ’s blood. |

| − | In some of the legends about Merlin, he is often associated with a famous woman. In one version of the legend, he is the teacher of Morgan Le Fay. She is partly responsible for the downfall of Arthur and Camelot. In many modern renditions of the legend, Merlin and Morgan La Fay are shown to be enemies.<ref> Hoffman, Donald L. "Malory’s Tragic Merlin." Merlin: A Casebook (1991): 332-41</ref> This is not the case in the | + | In some of the legends about Merlin, he is often associated with a famous woman. In one version of the legend, he is the teacher of Morgan Le Fay. She is partly responsible for the downfall of Arthur and Camelot. In many modern renditions of the legend, Merlin and Morgan La Fay are shown to be enemies.<ref> Hoffman, Donald L. "Malory’s Tragic Merlin." Merlin: A Casebook (1991): 332-41</ref> This is not the case in the sources. In another story, he is shown to be infatuated with a beautiful young woman named Vivian. Merlin teaches her the arts of magic, and when she is powerful, she rejects and imprisons him in a magical forest. In one of the most popular stories on the death of Arthur, he is put to death by the enigmatic Lady of the Lake, the great sorceress, who was associated with the mystical sword Excalibur.<ref>Tolstoy, p 119</ref> |

<dh-ad/> | <dh-ad/> | ||

====The Druid Theory==== | ====The Druid Theory==== | ||

| − | Monmouth | + | Monmouth, credited with introducing Merlin's character to the wider world, claimed that he was a figure from history. Camelot's wizard was based on some stories circulating in Wales or possibly Cornwall for centuries. These areas still have a strong Celtic heritage, in the Dark Ages and down to the present day. Some have speculated that Merlin was based on a Druid, a Celtic priest, or a learned class member. These Druids are often portrayed as sorcerers and magicians and were very powerful. It is possible, according to some sources, that vestiges of druidism survived in the British Isles. |

| − | There is evidence from Welsh hagiographies and poems that ‘druids’ were still active in the 6th century, even though | + | There is evidence from Welsh hagiographies and poems that ‘druids’ were still active in the 6th century, even though the Romans had officially suppressed them. One 9th century Welsh poem by Genius referred to druids helping a Brythonic king and was his court magician and most trusted adviser. It is quite possible that Merlin was based on some folk memory of a druid and that Monmouth heard of these tales.<ref>Tolstory, p. 111</ref> There is the real possibility that one of the Brythonic war-leaders, upon whom the character of King Arthur is possibly based employed one such druid. In the Dark Ages, it was quite common for rulers to have court magicians, who legitimized their rule and gave them more power. |

====Was Merlin a war-leader==== | ====Was Merlin a war-leader==== | ||

| − | In the Welsh sources and | + | In the Welsh sources and some later English sources, there are many references to Ambrosius Aurelianus. He is portrayed as a powerful war-leader or as a king of the Britons. In Bede’s History of the English People, he is portrayed as the last of the Romans and possibly descended from an Emperor. He rallies the scattered Britons after they had been defeated several times by the pagan invaders. He leads them to victory over the invaders, and he establishes a powerful kingdom. Ambrosius Aurelianus is a rather paradoxical figure. At once of Roman descent, he is also a powerful magician. In one Welsh account, dating from the 9th century AD, he is shown as living in an enchanted castle guarded by dragons. |

| − | In one story he is shown winning a duel with some Royal magicians and after this, he | + | In one story, he is shown winning a duel with some Royal magicians, and after this, he can simply demand the lands of a powerful neighboring warlord.<ref>Hoffman, p. 302</ref> Ambrosius Aurelianus is also shown to have been a prophet, and like Merlin, he was able to foretell the rise and fall of Kingdoms. According to some sources, he prophesied the end of the Saxon kingdoms and the rise of the Normans. Many believe that Merlin was based on this sorcerer, who was also a warrior-king. |

| − | However, Geoffrey of Monmouth in his tales has Ambrosius Aurelianus as the uncle of King Arthur, who died before his birth and is a friend of Merlin. | + | However, Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his tales, has Ambrosius Aurelianus as the uncle of King Arthur, who died before his birth and is a friend of Merlin. The character of Ambrosius Aurelianus, preserved in folktales and poems, may have been one of the models for the court magician of Camelot. It appears that Monmouth in his Vita Merlini based some stories on the adventures of Ambrosius Aurelianus. |

<div class="portal" style='float:right; width:35%'> | <div class="portal" style='float:right; width:35%'> | ||

====Related Articles==== | ====Related Articles==== | ||

| − | {{#dpl:category=Historically Accurate|ordermethod=firstedit|order=descending|count= | + | {{#dpl:category=Historically Accurate|ordermethod=firstedit|order=descending|count=9}} |

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | |||

==== Myrddin Wyllt==== | ==== Myrddin Wyllt==== | ||

| − | Many believe that the original model of Merlin was a Northern British bard, prophet, hermit, and madman. Myrddin Wyllt was a bard and he served a powerful local king in what is now Southern Scotland. The lord is at war against other local kings. In a terrible battle in about 576 AD, Myrddin witnessed | + | Many believe that the original model of Merlin was a Northern British bard, prophet, hermit, and madman. Myrddin Wyllt was a bard, and he served a powerful local king in what is now Southern Scotland. The lord is at war against other local kings. In a terrible battle in about 576 AD, Myrddin witnessed his king's death and the destruction of his army. This war was to prove a disaster for all the parties because it weakened the Britons so much that they easily succumbed to the invading Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Myrddin went mad after the death of his king and the destruction of his kingdom. He fled to the vast Caledonian forest, and he lived with the animals. He did not wear any clothes and still grieved over the death of his king until his death. |

| − | + | He acquired the gift of prophecy, and many came to consult him about the future. Many prophecies are attributed to him, including a revival of Celtic power in the British Isles. In some sources, he is known as Lailoken, and he is shown as living near a village in the Lowlands of Scotland. There was once a grave of Myrdin to be seen near the village of Pebbles in the Scottish Borders <ref>Ford, Patrick K. "The Death of Merlin in the Chronicle of Elis Gruffydd." Viator 7 (1976): 379-390 </ref>. Many believe that Geoffrey of Monmouth based Merlin on Myrddin Wyllt. | |

| − | There are some similarities between the two figures. For example, the name Myrddin is somewhat similar to Merlin. It has been speculated that Monmouth changed Myrddin’s name so that it was more acceptable to an English-speaking audience <ref>Jankulak, p. 113</ref>. Then Myrddin was a prophet and Merlin is primarily a prophet in Monmouth’s work. It is only in a later version of the Arthurian legend that Merlin became a powerful sorcerer. It seems that Geoffrey may have based the great magician on the mad prophet, who roamed the Scottish forests. | + | There are some similarities between the two figures. For example, the name Myrddin is somewhat similar to Merlin. It has been speculated that Monmouth changed Myrddin’s name so that it was more acceptable to an English-speaking audience <ref>Jankulak, p. 113</ref>. Then Myrddin was a prophet, and Merlin is primarily a prophet in Monmouth’s work. It is only in a later version of the Arthurian legend that Merlin became a powerful sorcerer. It seems that Geoffrey may have based the great magician on the mad prophet, who roamed the Scottish forests. |

====Conclusion==== | ====Conclusion==== | ||

| − | + | Merlin's character is known to many, even by those who have never read or seen a story based on the Arthurian legends. Geoffrey de Monmouth was a crucial figure in the development of the character. However, while he was a fictional writer, he did base Arthur’s magician on a historical figure. Monmouth appears to have been aware of Ambrosius Aurelianus, and this figure was influential in the development of the character, who was the mentor of Arthur. | |

| − | + | The real likelihood that de Monmouth may have based Merlin on some folklore about a druid or several druids. It seems likely that the wizard was based on the Scottish prophet and hermit Myrddin Wyllt. There are undoubtedly similarities between the mad Scottish prophet and Merlin. It appears that he was a composite character and is an amalgam of Myrddin, Ambrosius Aurelianus, and some unidentified druid or druids. | |

====Further Reading==== | ====Further Reading==== | ||

| Line 56: | Line 57: | ||

Loomis, Roger Sherman. Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance (USA, Columbia University Press, 1937). | Loomis, Roger Sherman. Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance (USA, Columbia University Press, 1937). | ||

| − | + | ||

====References==== | ====References==== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

[[Category:Wikis]][[Category:British History]] [[Category: Historically Accurate]] | [[Category:Wikis]][[Category:British History]] [[Category: Historically Accurate]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Updated December 5, 2020 | ||

Latest revision as of 23:26, 19 September 2021

Merlin is perhaps the best-known wizard or magician in popular culture. He is one of the key characters in the much-loved Arthurian legends. In these stories, he is the court magician and mentor of the ruler of Camelot. Since the Middle Ages, Merlin has become a by-word for the practice of magic. He has been portrayed countless times in books, plays, and movies. However, was Merlin based on a real-life character? This article will discuss if he was based on an actual historical figure or merely a fictional character, the product of medieval writers and poets. It will discuss possible candidates for the original Merlin, and these include a Scottish prophet, an early British king, and the theory that he was a Celtic priest, a druid.

The context of the story of Merlin

The Arthurian Cycle of stories and Merlin's legend is based on more or less historical events that occurred in the wake of the collapse of Roman power in the West. In 410 AD, the last Roman legion left Britain, and the natives had to fend for themselves. Several small Brythonic kingdoms were faced with an invasion by pagan Saxons and other Germanic tribes. This was an era when great warlords emerged, such as Vortigern, who fought against the barbarians. This is when legendary warrior-kings, such as Uther Pendragon and Arthur, were said to rule.

The Brythonic kingdoms were all Christian, but they were also Roman-Celtic. They were pushed out of England's rich lowlands into the highlands of Cornwall, Wales, and Scotland. At this time, popularly known as the Dark Ages, many pre-Christian practices remained, and much of the population was still half-pagan. There were still old-style magicians and prophets, who were believed to have special powers, such as those possessed by Merlin, even by clerics and monks [1].

The sources of Merlin

There is no one fixed version of the story of Merlin. He is first mentioned in the History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey de Monmouth. The same author then wrote a book that purports to be Merlin's prophecies (1130 AD). In these prophecies, well-known historical figures were represented by animals and their futures told in riddles. Monmouth claims that the prophecies and the figure of Merlin are based on ancient oral sources. He shows Merlin to be a key member of King Arthur’s inner circle.

In his later work, the Vita Merlini, he elaborated on the story of Camelot's wizard. Many have accused Geoffrey of Monmouth of simply inventing the famous wizard and prophet. In the 13th century, a French poet, Robert de Boron, wrote an epic poem on the magician based on Monmouth's work. Some of this work is lost, but it was very influential in the popularity of Merlin's character.[2] In later centuries, Thomas Mallory and other writers greatly elaborated on the wizard's story. They did not emphasize his powers of prophecy but concentrated on his supernatural powers.

The life and adventures of Merlin

According to most sources, Merlin was the son of an incubus or a preternatural being, often viewed as demonic. He may have been the son of a Royal Princess, from the north of England. He was baptized as a Christian, and this purified him, but he was a paradoxical figure, good, but also tainted by his demonic inheritance.

Merlin was a powerful prophet and magician from an early age and is shown as helping a Brythonic ruler to defeat the Anglo-Saxon invaders while still a teenager. He was often shown to be also a shapeshifter, who is at once an older man, a handsome youth, and even a deer. One of his most famous feats was to build Stonehenge by transporting stones from Ireland. He is a key figure in the Arthurian legends and is shown as an advisor to King Arthur’s father, Uther Pendragon. He helped Uther to disguise himself and to impregnate the wife of his enemy. From this act, the future King Arthur was born. Merlin is a critical figure in the ‘Story of the Sword.’ He predicts that the man who takes the sword from the stone (or anvil in some accounts) is the rightful monarch of Britain. Merlin is typically shown to be the mentor and teacher of Arthur. It is he who helps him to become King of the Britons.

In one version, offered by Geoffrey de Monmouth, the wizard married a beautiful woman and retired to study the stars. However, in another version, Merlin becomes Arthur’s advisor and his court magician.[3] Some stories clarify that Merlin was partly responsible for Arthurs victories. He is also shown as helping him to gather enough knights for the fabled Round Table. In some French accounts, the wizard is a significant figure in the Holy Grail and the Knights of the Round Tables quest for the chalice that held Christ’s blood.

In some of the legends about Merlin, he is often associated with a famous woman. In one version of the legend, he is the teacher of Morgan Le Fay. She is partly responsible for the downfall of Arthur and Camelot. In many modern renditions of the legend, Merlin and Morgan La Fay are shown to be enemies.[4] This is not the case in the sources. In another story, he is shown to be infatuated with a beautiful young woman named Vivian. Merlin teaches her the arts of magic, and when she is powerful, she rejects and imprisons him in a magical forest. In one of the most popular stories on the death of Arthur, he is put to death by the enigmatic Lady of the Lake, the great sorceress, who was associated with the mystical sword Excalibur.[5]

The Druid Theory

Monmouth, credited with introducing Merlin's character to the wider world, claimed that he was a figure from history. Camelot's wizard was based on some stories circulating in Wales or possibly Cornwall for centuries. These areas still have a strong Celtic heritage, in the Dark Ages and down to the present day. Some have speculated that Merlin was based on a Druid, a Celtic priest, or a learned class member. These Druids are often portrayed as sorcerers and magicians and were very powerful. It is possible, according to some sources, that vestiges of druidism survived in the British Isles.

There is evidence from Welsh hagiographies and poems that ‘druids’ were still active in the 6th century, even though the Romans had officially suppressed them. One 9th century Welsh poem by Genius referred to druids helping a Brythonic king and was his court magician and most trusted adviser. It is quite possible that Merlin was based on some folk memory of a druid and that Monmouth heard of these tales.[6] There is the real possibility that one of the Brythonic war-leaders, upon whom the character of King Arthur is possibly based employed one such druid. In the Dark Ages, it was quite common for rulers to have court magicians, who legitimized their rule and gave them more power.

Was Merlin a war-leader

In the Welsh sources and some later English sources, there are many references to Ambrosius Aurelianus. He is portrayed as a powerful war-leader or as a king of the Britons. In Bede’s History of the English People, he is portrayed as the last of the Romans and possibly descended from an Emperor. He rallies the scattered Britons after they had been defeated several times by the pagan invaders. He leads them to victory over the invaders, and he establishes a powerful kingdom. Ambrosius Aurelianus is a rather paradoxical figure. At once of Roman descent, he is also a powerful magician. In one Welsh account, dating from the 9th century AD, he is shown as living in an enchanted castle guarded by dragons.

In one story, he is shown winning a duel with some Royal magicians, and after this, he can simply demand the lands of a powerful neighboring warlord.[7] Ambrosius Aurelianus is also shown to have been a prophet, and like Merlin, he was able to foretell the rise and fall of Kingdoms. According to some sources, he prophesied the end of the Saxon kingdoms and the rise of the Normans. Many believe that Merlin was based on this sorcerer, who was also a warrior-king.

However, Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his tales, has Ambrosius Aurelianus as the uncle of King Arthur, who died before his birth and is a friend of Merlin. The character of Ambrosius Aurelianus, preserved in folktales and poems, may have been one of the models for the court magician of Camelot. It appears that Monmouth in his Vita Merlini based some stories on the adventures of Ambrosius Aurelianus.

Related Articles

- How historically accurate is the Gladiator

- How Historically Accurate is season 1 of Versailles

- How Historically Accurate is Season 4 of The Last Kingdom

- How historically accurate is the movie Hurricane (aka Mission of Honor)

- How Historically Accurate is the Rise of Empires: Ottoman Series

- How historically accurate is Martin Scorsese's movie Silence

- How Historically Accurate Is Victoria and Abdul

- How Historically Accurate Is The King

- Was the story of Jekyll and Hyde based on real-life characters

Myrddin Wyllt

Many believe that the original model of Merlin was a Northern British bard, prophet, hermit, and madman. Myrddin Wyllt was a bard, and he served a powerful local king in what is now Southern Scotland. The lord is at war against other local kings. In a terrible battle in about 576 AD, Myrddin witnessed his king's death and the destruction of his army. This war was to prove a disaster for all the parties because it weakened the Britons so much that they easily succumbed to the invading Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Myrddin went mad after the death of his king and the destruction of his kingdom. He fled to the vast Caledonian forest, and he lived with the animals. He did not wear any clothes and still grieved over the death of his king until his death.

He acquired the gift of prophecy, and many came to consult him about the future. Many prophecies are attributed to him, including a revival of Celtic power in the British Isles. In some sources, he is known as Lailoken, and he is shown as living near a village in the Lowlands of Scotland. There was once a grave of Myrdin to be seen near the village of Pebbles in the Scottish Borders [8]. Many believe that Geoffrey of Monmouth based Merlin on Myrddin Wyllt.

There are some similarities between the two figures. For example, the name Myrddin is somewhat similar to Merlin. It has been speculated that Monmouth changed Myrddin’s name so that it was more acceptable to an English-speaking audience [9]. Then Myrddin was a prophet, and Merlin is primarily a prophet in Monmouth’s work. It is only in a later version of the Arthurian legend that Merlin became a powerful sorcerer. It seems that Geoffrey may have based the great magician on the mad prophet, who roamed the Scottish forests.

Conclusion

Merlin's character is known to many, even by those who have never read or seen a story based on the Arthurian legends. Geoffrey de Monmouth was a crucial figure in the development of the character. However, while he was a fictional writer, he did base Arthur’s magician on a historical figure. Monmouth appears to have been aware of Ambrosius Aurelianus, and this figure was influential in the development of the character, who was the mentor of Arthur.

The real likelihood that de Monmouth may have based Merlin on some folklore about a druid or several druids. It seems likely that the wizard was based on the Scottish prophet and hermit Myrddin Wyllt. There are undoubtedly similarities between the mad Scottish prophet and Merlin. It appears that he was a composite character and is an amalgam of Myrddin, Ambrosius Aurelianus, and some unidentified druid or druids.

Further Reading

Geoffrey of Monmouth Lewis Thorpe (ed.). The History of the Kings of Britain (London, Penguin Classics. Penguin Books, 1977).

Loomis, Roger Sherman. Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance (USA, Columbia University Press, 1937).

References

- Jump up ↑ Tolstoy, Nikolai. The Quest for Merlin (London, H. Hamilton, 1985), p 14

- Jump up ↑ Jankulak, Karen. Geoffrey of Monmouth (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2010), p. 11

- Jump up ↑ Tolstoy, p. 119

- Jump up ↑ Hoffman, Donald L. "Malory’s Tragic Merlin." Merlin: A Casebook (1991): 332-41

- Jump up ↑ Tolstoy, p 119

- Jump up ↑ Tolstory, p. 111

- Jump up ↑ Hoffman, p. 302

- Jump up ↑ Ford, Patrick K. "The Death of Merlin in the Chronicle of Elis Gruffydd." Viator 7 (1976): 379-390

- Jump up ↑ Jankulak, p. 113

Updated December 5, 2020