Difference between revisions of "What Was the Significance of the Near East Middle Bronze Age System"

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

===How the System Worked=== | ===How the System Worked=== | ||

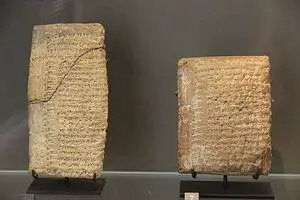

| − | [[File: HammurabiCode.jpg|300px|thumbnail|left| | + | [[File: HammurabiCode.jpg|300px|thumbnail|left| Hammurabi's Law Code]] |

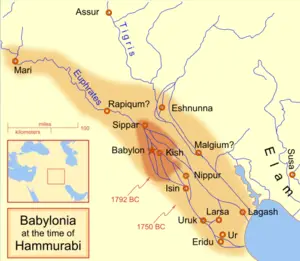

[[File: Hammurabis_Babylonia.png|300px|thumbnail|right| Map Showing the Extent of Hammurabi’s Conquests in Mesopotamia]] | [[File: Hammurabis_Babylonia.png|300px|thumbnail|right| Map Showing the Extent of Hammurabi’s Conquests in Mesopotamia]] | ||

The geopolitical system that the states of the Near East constructed in the early second millennium BC is believed by many scholars to have resembled the later, better known Late Bronze Age system in the region. The manner in which the major states dealt with the smaller, weaker states was also probably similar, although much less formal and rigid. <ref> Munn-Rankin, J. M. “Diplomacy in Western Asia in the Early Second Millennium B.C.” <i>Iraq</i> 18 (1956) p. 75</ref> | The geopolitical system that the states of the Near East constructed in the early second millennium BC is believed by many scholars to have resembled the later, better known Late Bronze Age system in the region. The manner in which the major states dealt with the smaller, weaker states was also probably similar, although much less formal and rigid. <ref> Munn-Rankin, J. M. “Diplomacy in Western Asia in the Early Second Millennium B.C.” <i>Iraq</i> 18 (1956) p. 75</ref> | ||

Revision as of 00:53, 4 January 2021

There is a common and unfortunate attitude among many that geopolitical sophistication is strictly a modern phenomenon, coinciding with advances in communication technology. Although it is true that modern technological inventions such as the wireless radio, telephone, automobile, airplane, and internet, just to name a few, have made international diplomacy more convenient, the art of political negotiation is as old as humanity. As modern scholars made great advances in the fields of philology, archaeology, and history in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it became clear that many medieval and ancient societies developed geopolitical systems that were as intricate as any today.

The Late Bronze Age (c. 1550-1200 BC) system of the Near East, often known as the “Great Powers Club,” has been well-researched by modern scholars thanks to an abundance of texts. Often overlooked, though, is the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2100-1550 BC) system of the Near East, which included such notable kingdoms as Babylon, Mari, Assyria, Qatna, and Yamhad, due to a combination of its antiquity and fewer available written documents. With that said, modern scholars have been able to compile histories of the major states of the period to determine that they had developed a geopolitical system that although not as expansive as the one their Late Bronze Age successors built, was still complex and possibly served as a template for the later system.

Contents

[hide]The People and Kingdoms of the Middle Bronze Age System

In order to understand the Near East’s Middle Bronze Age system, one must begin with the people who were the driving force behind it – the Amorites. Like the Akkadians who came before them in Mesopotamia and the Canaanites in the Levant, the Amorites were a Semitic ethnic group, but they were a much more restless group than their predecessors. The Amorites probably originated somewhere in Syria, although that is not known for sure, and then swept into Mesopotamia and the Levant as nomadic war bands in the late third millennium BC, helping to bring about the collapse of the neo-Sumerian Ur III Dynasty. Entering the region as warbands, the Amorites chose to stay, adopting the cuneiform script, the Akkadian language, and establishing new kingdoms. [1]

There were about six kingdoms at the core of the Middle Bronze Age geopolitical system, with approximately three or four states that existed on the periphery of the system. The Kingdom of Yamhad was located in northern Syria with its capital in Halab, which is the location of the modern city of Aleppo. In addition to Halab, the Yamhad Dynasty controlled several other cities and smaller kingdoms, including the state of Alalakh. Located next to Yamhad in western Mesopotamia was the Kingdom of Mari. Mari and Yamhad shared not only geography and ethnicity, but it appears their dynasties were closely related through familial ties. The best known Yamhad king was Yarim-Lim (ruled c. 1780-1765 BC), and there were two other kings in Yamhad with the name in addition to two Mari kings with the “Lim” designation in their names. The word “Lim” was probably an Amorite word meaning “people” or “folk,” [2] although it could indicate that both kingdoms originated from related families or clans.

Archaeological work at Mari has yielded the greatest cache of Middle Bronze Age primary source evidence in the form of more than 17,000 cuneiform tablets, known collectively as the “Mari archives.” The Mari archives, which are dated from the twenty-fourth to the eighteenth centuries BC, were discovered primarily in the ruins of the royal palace, so their content primarily relates to diplomacy, war, and trade, although a number of the texts also concern religion. [3] Since the texts were discovered in Mari, most of diplomatic tablets are letters received by the Mari kings from the kings of the other states, although some were written but unsent. The letters demonstrate that Mari and Yamhad had an especially close relationship, but that theirs was just one of many in a larger system.

To the south of Yamhad was the Kingdom of Qatna. Qatna was headquartered in the eponymously named capital city, which was located about fifteen miles northeast of the modern city of Homs, Syria in the fertile Syrian plain, near the Orontes River. The names of the Qatna kings are known, but the precise chronology of their rule and their inclusive dates are blurred due to a dearth of written texts discovered in the city. With that said, Qatna’s archaeological remains have yielded what was once an impressive city of more than 250 acres in its prime. [4]

The other important Amorite kingdoms of the era were the dynasty established by Shamsi-Adad (reigned c. 1808-1776 BC) and the First Dynasty of Babylon, of which Hammurabi (c. 1792-1750 BC) was the most famous king. The Amorite states were joined by the kingdoms of Eshnunna and Lara in Mesopotamia and a number of other states on the geographic-cultural periphery of the system, including Elam, Middle Kingdom Egypt, Cyprus, and numerous states in Anatolia.

How the System Worked

The geopolitical system that the states of the Near East constructed in the early second millennium BC is believed by many scholars to have resembled the later, better known Late Bronze Age system in the region. The manner in which the major states dealt with the smaller, weaker states was also probably similar, although much less formal and rigid. [5]

Agreements between the kings took on religious connotations in addition to the obvious elements that concerned the temporal world. Important oaths between kingdoms were usually done with a divine “witness” in attendance and sealed with a sacrifice. [6] Although oaths were often broken, the religious aspect of the oaths served to give them a greater weight, as all parties involved would have shared similar beliefs, including the idea that such oaths were efficacious. Since oaths could be broken, though, often the most popular way to bind one kingdom to another was through diplomatic marriage.

The Mari archives have revealed that the major powers of the Middle Bronze Age Near East regularly used their sons and daughters to tie kingdoms together for strategic military and political factors as well as trade. Ishi-Adad (ruled. C. early 1700s BC), the King of Qatna, is recorded as sending his daughter to marry Shami-Adad’s son, Yasmah-Adad (reigned c. 1794-1776 BC), who was the king of Mari at the time. Shamsi-Adad had conquered most of northern Mesopotamia and temporarily vanquished the Lim Dynasty, sending them into exile in Yamhad. Shamsi-Adad then made his two sons regional kings, giving the woefully inept Yasmah-Adad control of Mari. As Ishi-Adad sent his daughter to Mari, he apparently had some doubts as indicated by the letter he sent with her.

“I am placing in your lap my flesh and my future. The handmaid (i.e., my daughter) that I give you, may God make her attractive to you. I am placing in your lap my flesh and future, for this House has now become yours and the House of Mari has now become mine. Whatever you desire, just write me and I will give it to you. All over my land, whatever the king (Samsi-Addu) has requested, I myself have never held it back. Why is it that whatever I desire from the king, he does not give it? Let him fulfill request as I fulfill yours.” [7]

The marriage alliance between Qatna and Shamsi-Adad’s Mari was not the only example from the Mari archives, though. After Shamsi-Adad died, presumably on the battlefield, and his son was driven from Mari, the Lim Dynasty returned to power thanks to Yarim-Lim of Yamhad. Yarim-Lim sent his daughter, Shibtu, to marry the recently reinstalled Zimri-Lim (reigned c. 1775-1762 BC) in Mari. Zimri-Lim later lamented in a letter to his father-in-law that as much as he has upheld his end of the alliance, Yamhad could do more to control the trade routes.

“However, in my heart I had the following thought: ‘It is my father who, having brought me to my throne, (is the one) who will strengthen me and secure the foundation of my throne.’ Now, ever since I came to the throne many days ago, I could look ahead only to wars and battles. I have never brought in a full harvest (in peace). If in truth (you are) my father, make it your business to strengthen me and to secure the foundation of my throne. My father should pay attention to what is in this letter of mine. All merchants in Imar who control grain should send boats on their say so as to bring calm in the land.” [8]

Zimri-Lim apparently thought twice about sending the sternly worded letter, because it was found in Mari, not Halab/Aleppo. The letter does demonstrate the central role that trade played in the Middle Bronze Age system – it was the one thing that drew the often feuding kingdoms together. The Middle Bronze Age kingdoms were linked by a variety of trade routes that went overland, down the Euphrates River, and even on the Mediterranean Sea and the Persian Gulf. The most lucrative and busy of the trade routes connected Qatna to Mari via Tadmor. Mari had access to the Euphrates River, while Qatna was close to the Mediterranean Sea, giving it relatively easy access to Egypt and Cyprus. Mari was the major supplier of tin in the region, [9] while Qanta produced wood and horses. Precious vessels, copper, fabrics, and garments flowed into Qatna from Cyprus, before being moved to the other kingdoms, and metallurgy, glass, faience, ivory, and bronze items were manufactured in the Yamhad controlled city of Alalakh. [10] As much as the Middle Bronze Age kingdoms put a premium on trade and diplomacy, there were occasional wars between the powers.

For the most part, wars were quite limited in the Middle Bronze Age Near East, being relegated primarily to border battles over vassal/proxy kingdoms and cities. There were two periods, though, when war did engulf most of the region. The first period of major warfare was when Shamsi-Adad conquered much of the region. The second period of major warfare took place when Hammurabi of Babylon expanded his kingdom to include most of Mesopotamia. In the lead up to Hammurabi’s conquests, political posturing took place between the major kingdoms, as alliances were routinely made and broken. For instance, Hammurabi I of Yamhad (ruled c. 1765-1760 BC) (Hammurabi was a common Amorite name) was aligned with Mari, Elam, Larsa, and Eshnunna against Babylon, but when he saw that his namesake in the south would not be denied he made the politically prudent choice of siding with Babylon. [11] Although Hammurabi of Babylon proved to be successful in his military endeavors, he was at least partially responsible for the collapse of the Middle Bronze Age system.

The End of the System

Hammurabi’s conquest of his neighbors put an end to the dynasties in Larsa, Eshnunna, and Mari, [12] which threw the entire system into political turmoil. Despite the instability Hammurabi caused, it was not the end of the system.

Despite surviving the Babylonian onslaught, Yamhad and Qatna were not spared the extreme political transition that was taking place in the period. Yamhad was destroyed by the Hittites in 1595 BC, [13] and although Qatna survived into the Late Bronze Age, it became a virtual buffer state between the Late Bronze Age powers of Egypt, Mitanni, and Hatti. [14]

Conclusion

The people of the Middle Bronze Age Near East developed a sophisticated geopolitical system that rivaled any similar system in the pre-modern world and in many ways was just as effective as most modern geopolitical systems. The major powers dealt with each other in primarily peaceful ways through diplomacy and trade for approximately 500 years before the Middle Bronze Age transitioned into the Late Bronze Age. Eventually new states arose in the Late Bronze Age that replaced the Middle Bronze Age kingdoms, but there is little doubt that they were influenced by the earlier states and their system.

References

- Jump up ↑ Pitard, Wayne T. “Before Israel: Syria-Palestine in the Bronze Age.” In The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Edited by Michael Coogan. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pgs. 34-36

- Jump up ↑ Malamat, Abraham. “Mari.” Biblical Archaeologist 34 (1971) p. 9

- Jump up ↑ Sasson, Jack M. From the Mari Archives: An Anthology of Old Babylonian Letters. (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2015), pgs. 3-9

- Jump up ↑ Pitard, p. 31

- Jump up ↑ Munn-Rankin, J. M. “Diplomacy in Western Asia in the Early Second Millennium B.C.” Iraq 18 (1956) p. 75

- Jump up ↑ Munn-Rankin, p. 84

- Jump up ↑ Sasson, p. 104

- Jump up ↑ Sasson, pgs. 81-82

- Jump up ↑ Kuhrt, Amélie. The Ancient Near East: c. 3000-330 BC. (London: Routledge, 2010), p. 101

- Jump up ↑ Yener, K. Aslihan. “The Anatolian Middle Bronze Age Kingdoms and Alalakh: Mukish, Kanesh, and Trade.” Anatolian Studies 57 (2007) p. 152

- Jump up ↑ Smith, Sidney. “Yarim-Lim of Yamḫad.” Rivista degli studi orientali 32 (1957) p. 157

- Jump up ↑ Mieroop, Marc van de. A History of the Ancient Near East: ca. 2000-323 BC. Second Edition. (London: Blackwell, 2007), p. 111

- Jump up ↑ Macqueen, Jack M. The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), p. 44

- Jump up ↑ Pitard, p. 43