Difference between revisions of "What is the history of contested presidential elections in the United States?"

(→Contested Presidential Elections in the 19th Century) |

(→Later Contested Elections) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==Later Contested Elections== | ==Later Contested Elections== | ||

| − | While the 19th century was known for sometimes fractious and contested elections that sometimes were drawn out, after this time elections were relatively less dramatic or were simply settled more clearly through the electoral college. Among the most controversial elections in the 20th century for president was the 1960 election. This was the closest election in the 20th century, where Richard Nixon (Republican) competed against John F. Kennedy (Democratic). Texas and Illinois allowed Kennedy to win, where he only received 100,000 more votes in total (or 0.2 of the electorate) to defeat Nixon. What made it controversial was the close race, where voter fraud was widely speculated by the Republicans. Southern Texas and Chicago became the focus of the controversy and accusations of the Richard Daley, then mayor of Chicago, using the political machine to turn out voters, including possibly deceased individuals supposedly casting votes, led to Republicans crying foul. While prominent Republicans were calling for an investigation into election tampering and fraud, Nixon ultimately chose not to pursue and legal challenges. Instead, he focused on running in another election (1968), which he won in a landslide. | + | While the 19th century was known for sometimes fractious and contested elections that sometimes were drawn out, after this time elections were relatively less dramatic or were simply settled more clearly through the electoral college. Among the most controversial elections in the 20th century for president was the 1960 election. This was the closest election in the 20th century, where Richard Nixon (Republican) competed against John F. Kennedy (Democratic). Texas and Illinois allowed Kennedy to win, where he only received 100,000 more votes in total (or 0.2 of the electorate) to defeat Nixon. What made it controversial was the close race, where voter fraud was widely speculated by the Republicans. Southern Texas and Chicago became the focus of the controversy and accusations of the Richard Daley, then mayor of Chicago, using the political machine to turn out voters, including possibly deceased individuals supposedly casting votes, led to Republicans crying foul. While prominent Republicans were calling for an investigation into election tampering and fraud, Nixon ultimately chose not to pursue and legal challenges. Instead, he focused on running in another election (1968), which he won in a landslide.<ref>For more on the 1960 election, see: Kallina, E.F., 2011. <i>Kennedy v. Nixon: the presidential election of 1960</i>. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL.</ref> |

| − | More recently, the 2000 election between Al Gore and George Bush resulted in a contested election that was ultimately decided by the Supreme Court. In this election, Gore won the popular vote and 266 electoral votes. However, he needed Florida to obtain the needed 270 electoral votes. Florida resulted in a razor-thing margin for Bush, with the total being 537 more votes for Bush (margin of 0.009%). After a series of lawsuits, the Supreme Court, in a well-publicized (Gore vs. Bush) 5-4 decision, decided to stop the recount occurring through out the state of Florida, leading to Bush's triumph. Controversy also revolved around ballots that were not counted due to technical or voting errors. | + | More recently, the 2000 election between Al Gore and George Bush resulted in a contested election that was ultimately decided by the Supreme Court. In this election, Gore won the popular vote and 266 electoral votes. However, he needed Florida to obtain the needed 270 electoral votes. Florida resulted in a razor-thing margin for Bush, with the total being 537 more votes for Bush (margin of 0.009%). After a series of lawsuits, the Supreme Court, in a well-publicized (Gore vs. Bush) 5-4 decision, decided to stop the recount occurring through out the state of Florida, leading to Bush's triumph. Controversy also revolved around ballots that were not counted due to technical or voting errors.<ref>For more on the 2000 election, see: Gottfried, T., 2002. <i>The 2000 election: Thirty-six days of discord.</i>, Headliners. Millbrook Press, Brookfield, Conn. </ref> |

[[File:PresidentialCounty1960Colorbrewer.gif|thumb|left|Figure 2. Higher percentage of votes for Kennedy in Texas and Illinois helped put Kennedy in the White House in 1960. ]] | [[File:PresidentialCounty1960Colorbrewer.gif|thumb|left|Figure 2. Higher percentage of votes for Kennedy in Texas and Illinois helped put Kennedy in the White House in 1960. ]] | ||

Revision as of 18:20, 10 November 2020

In 2020, the presidential election appears to be contested by some groups, including the president himself. Contested presidential elections have been a part of US history and in the 19th century they were more common. In many cases, it has often been because of the electoral college and popular vote discrepancies. In general, contested elections have been usually peacefully resolved, even if some parties continue to feel grieved long after the vote.

Contents

Contested Presidential Elections in the 19th Century

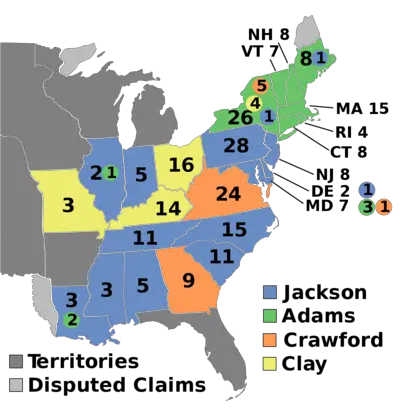

The 1824 presidential election featured four main candidates, with the candidates being Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford (Figure 1). Because there were four main candidates, with each having some support, the results led to a contested election in which no candidate was able to obtain the majority of the electoral college. This election featured only one party, the Democratic-Republican Party, although numerous factions existed, which eventually gave rise to the Democratic and Republican parties. As the majority of the electoral college votes are needed to become president, the election led to one of the few times the House of Representatives ultimately chose who became president. Andrew Jackson had won the most electoral votes, but he ultimately proved unsuccessful and John Quincy Adams was voted by the House. It was (likely) the first election where the winner did not receive a majority of the popular vote, where Adams only obtained about 32% of the total vote. Clay, who finished fourth, lent Adams sup, which helped to overcome Jackson's challenge. Unlike today, more than a couple of states split their electoral votes based on districts. Maryland, Louisiana, Illinois, and New York split their votes. The help by Clay led Jackson to accuse Adams of striking a corrupt bargain, as Clay was appointed Secretary of State in the Adams' administration. That message and accusation of corruption helped Jackson win the next presidential election.[1]

Perhaps the most disputed election, and certainly one with a controversial result, in US history is the presidential election of 1876, which saw Rutherford Hayes (Republican) vs. Samuel J. Tilden (Democratic). In that election, Tilden had obtained the majority of the popular votes and, initially, the majority of the electoral votes (Tilden had won 184 electoral votes to Hayes's 165). However, 20 electoral votes were unresolved from the states of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Each party declared their candidate won but ultimately it could not be resolved with ballots counted or the electoral votes. In the so-called compromise of 1877, the election was resolved by the Democratic party agreeing to give 20 electoral votes to Hayes in exchange for the Republicans withdrawing troops from the South, who had been there since the end of the Civil War, and formally ending Reconstruction. That compromise had long-lasting effects on the suppression of black voters, particularly as Jim Crow laws gained power in the South, but in the immediate sense it resolved the election by allowing the Democrats to at least get their main aims in getting rid of Federal troops and Reconsruction laws. That election was notable for having the highest voter turnout (81.8%) in US history and the narrowest electoral college victory for the winning candidate (185 to 184).[2]

The 1888 presidential election saw Democratic President Grover Cleveland of New York run against Republican Indiana U.S. Senator Benjamin Harrison. Harrison was able to carry the electoral votes and beat out Cleveland who carried the majority of voters. The electoral results were 233 vs. 168 for Harrison. What marred the election was the Harrison campaign was caught by the Cleveland campaign in attempting to buy votes. Local leaders in Indiana were promised funds to buy votes in Indiana and the letter stating this was found by the Democratic party. In fact, besides Indian, there could have been attempts to buy votes in New York, which may explain how Cleveland lost his home state that he was widely expected to win. While Cleveland ultimately lost his re-election bid, he was able to successfully run in 1880, becoming the only president with non-consecutive terms.[3]

Later Contested Elections

While the 19th century was known for sometimes fractious and contested elections that sometimes were drawn out, after this time elections were relatively less dramatic or were simply settled more clearly through the electoral college. Among the most controversial elections in the 20th century for president was the 1960 election. This was the closest election in the 20th century, where Richard Nixon (Republican) competed against John F. Kennedy (Democratic). Texas and Illinois allowed Kennedy to win, where he only received 100,000 more votes in total (or 0.2 of the electorate) to defeat Nixon. What made it controversial was the close race, where voter fraud was widely speculated by the Republicans. Southern Texas and Chicago became the focus of the controversy and accusations of the Richard Daley, then mayor of Chicago, using the political machine to turn out voters, including possibly deceased individuals supposedly casting votes, led to Republicans crying foul. While prominent Republicans were calling for an investigation into election tampering and fraud, Nixon ultimately chose not to pursue and legal challenges. Instead, he focused on running in another election (1968), which he won in a landslide.[4]

More recently, the 2000 election between Al Gore and George Bush resulted in a contested election that was ultimately decided by the Supreme Court. In this election, Gore won the popular vote and 266 electoral votes. However, he needed Florida to obtain the needed 270 electoral votes. Florida resulted in a razor-thing margin for Bush, with the total being 537 more votes for Bush (margin of 0.009%). After a series of lawsuits, the Supreme Court, in a well-publicized (Gore vs. Bush) 5-4 decision, decided to stop the recount occurring through out the state of Florida, leading to Bush's triumph. Controversy also revolved around ballots that were not counted due to technical or voting errors.[5]

General and Common Concerns

Interestingly, all of these contested elections often were resolved peacefully without violence. Arguably, the 1860 election was a heavily contested election, one which did not lead to a peaceful resolution as the Civil War was the result of this election. However, the results were generally clear, with Abraham Lincoln winning that election and capturing the majority of electoral votes. Only the 2000 election resulted in the Supreme Court getting involved, while the other controversial elections often led to either the losing candidates resolving to run again, and often winning the next time, or a compromise result was enacted between the parties (1876). The 20th century has generally seen mostly smooth elections where candidates obtain the majority of popular votes and electoral votes; however, the 2000 and 2016 election have shown that the popular vote often does not align with the electoral college vote even in the modern era.

Summary

The US presidential election system is complex in that it requires the majority of electoral college votes go to a single candidate. This has created controversial results both in the early history of the United States (e.g., 1826) but also in recent history, where candidates receiving the majority of the popular vote may not obtain the majority of the electoral college votes. Interestingly, early resolutions to this problem involved dividing states to divisible electoral votes, rather than giving the winner of the state popular vote automatically all of the electoral votes for the state. However, this still led to problems in 1826. More recently, only two states allow their electoral votes to be divided.

References

- ↑ For more on the 1824 election, see: Waldstreicher, D. (Ed.), 2013. A companion to John Adams and John Quincy Adams, Wiley-Blackwell companions to American history. Wiley-Blackwell, A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication, Malden, MA.

- ↑ For more on the 1876 election, see: Rehnquist, W.H., 2004. Centennial crisis: the disputed election of 1876, 1st ed. ed. Alfred A. Knopf : Distributed by Random House, New York.

- ↑ For more on the 1888 election, see: Wesser, R., 2019. Election of 1888. History of American Presidential Elections.

- ↑ For more on the 1960 election, see: Kallina, E.F., 2011. Kennedy v. Nixon: the presidential election of 1960. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

- ↑ For more on the 2000 election, see: Gottfried, T., 2002. The 2000 election: Thirty-six days of discord., Headliners. Millbrook Press, Brookfield, Conn.