Difference between revisions of "How Was Alaric Able to Sack Rome in AD 410"

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

====Suggested Readings==== | ====Suggested Readings==== | ||

| − | Bury, J. B. <i>[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0393003884/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0393003884&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=674cc418da52757c6a23d9153bed4b30 The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians]. </i> (New York: W. W. Norton, 1967) | + | * Bury, J. B. <i>[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0393003884/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0393003884&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=674cc418da52757c6a23d9153bed4b30 The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians]. </i> (New York: W. W. Norton, 1967) |

| − | + | * Sennigen, William B., and Arthur E.R. Boak. <i>[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/151159859X/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=151159859X&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=30e0c8a670cab9eddaa81a763aee31d9 The History of Rome to A.D. 565] </i> 6th Ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1977) | |

| − | Sennigen, William B., and Arthur E.R. Boak. <i>[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/151159859X/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=151159859X&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=30e0c8a670cab9eddaa81a763aee31d9 The History of Rome to A.D. 565] </i> 6th Ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1977) | + | * Kyle Harper, <i>[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0691166838/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0691166838&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=8847a0d9567c7a46530e846eddf769f7 The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire]</i> (Princeton University Press, 2017) |

| − | + | * John Boardman, edit. Jasper Griffen, Oswyn Murray, <i>[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0192802038/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0192802038&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=cf273774d1bac11c72c7b6dba59f6ce1 The Oxford History of the Roman World]</i> (Oxford University Press, 2001) | |

| − | Kyle Harper, <i>[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0691166838/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0691166838&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=8847a0d9567c7a46530e846eddf769f7 The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire]</i> (Princeton University Press, 2017) | + | * Bryan Ward-Perkins, ''[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0192807285/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0192807285&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=0aa209b468427b0b72f5320e69fcd25c The Fall of Rome: and the End of Civilization]'' (Oxford University Press, 2006) |

| − | |||

| − | John Boardman, edit. Jasper Griffen, Oswyn Murray, <i>[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0192802038/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0192802038&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=cf273774d1bac11c72c7b6dba59f6ce1 The Oxford History of the Roman World]</i> (Oxford University Press, 2001) | ||

| − | |||

| − | Bryan Ward-Perkins, ''[https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0192807285/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0192807285&linkCode=as2&tag=dailyh0c-20&linkId=0aa209b468427b0b72f5320e69fcd25c The Fall of Rome: and the End of Civilization]'' (Oxford University Press, 2006) | ||

====References==== | ====References==== | ||

Revision as of 00:35, 15 April 2018

Few scholars would argue that it would by hyperbole to say that the Visigoth sack of Rome in AD 410 was one of the true turning points in world history. For Rome, it was the first time that the city had been sacked by outsiders in over 800 years, when the Gauls last did the destructive deed in 390 BC. The Romans recovered nicely from the 390 BC sacking, with the majority of their cultural, political, and military achievements coming after that date. In fact, one could argue that Rome was strong because of the 390 BC sacking, as it was forced to reevaluate its military capabilities and how far its northern boundaries should be extended. The sacking in AD 410 was much different, though, as it came at a time when Rome had been in decline for over two centuries. In many ways, the sacking was the death knell of the once great city-state, which limped along for a few more decades before the last emperor of the west was deposed in AD 476.

It is said that Rome was not built in a day, which equally applies to its collapse and the sacking of the city in AD 410. Rome’s sacking was the end result of a ten year process of invasions and sieges led by Alaric I (ruled 395-410), king of the Visigoths. Alaric I was able to bring forth unmitigated destruction to Rome due to a number of factors. The Visigoth king proved to be a great military tactician who possessed a resolute character and was a keen judge of character. On the other side, the Roman Emperor Honorius (reigned 393-423) was weak, inexperienced, and prone to take bad advice, which ultimately led to the death of the only Roman commander who could stop Alaric I.

Alaric I and the Visigoths

Little is known about Alaric’s early life, although it is believed that he was born on the Peuce Island in the Danube River delta, near the Black Sea. Alaric’s people, the Visigoths, had attained federate status under Emperor Constantine I (ruled 306-337), which meant that they were required to fight for the Romans in exchange for a yearly allotment of grain. [1]

As a young man, Alaric marched alongside the Emperor Theodosius I (reigned 379-395), eventually acquiring a reputation for bravery, loyalty, and cleverness. Although Alaric was a German and not a Roman citizen, he desired to be a Roman general, which had become a possibility when the requirements for such an office changed during the Roman Empire. Still, it was difficult for a German to rise to such a high rank without a benefactor – Alaric believed his would be none other than the emperor, who was impressed with the young man’s abilities. Unfortunately for Alaric, his dreams of attainting the highest rank in the Roman army were dashed when Theodosius I died.[2] The young Visigoth warrior would have to look elsewhere for status.

In the year 395, some of Alaric’s ambitions were finally realized when he was elected king of the Visigoths at the age of thirty. The election made Alaric the first true Visigoth king,[3] but it did help him gain entry into the Roman elite. The title of Visigoth king must have seemed like an inferior door prize to Alaric I, because as soon as he was crowned he set out to punish Rome.

Alaric I led his Visigoth army into Roman territory and for a time it seemed that there was nothing the Western or Eastern emperors could do about it, until the Roman general Stilicho came to the rescue. Like Alaric, Stilicho was actually of German ancestry, but he was from the Vandal tribe and by the late fourth century his reputation as a excellent tactician and charismatic general preceded him, which eventually resulted in Theodosius I appointing him as the young Honorius’ regent. Honorius later married Stilicho’s daughter Thermania, placing the Vandal firmly in the imperial family. [4] Most now believe that Stilicho was the one who truly held the reins of power in the Western Roman Empire and that he largely controlled Alaric I’s early movements in southern Europe.

The Invasions of Italy and Sieges of Rome

Not long after Alaric I was elected king, he lead the Visigoth nation into southern Europe, embarking on a thirteen year orgy of plunder and devastation. The Visigoths first marched into the Balkans region in 397 and were met by little resistance. The emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, Arcadius (ruled 395-408), was weak like his brother Honorius and totally bereft of any military force that could stop the Visigoths. The only hope that Arcadius had was to appeal to his brother to send Stilicho and his army, but the general decided to sit back for awhile to see how the situation transpired.

Alaric I led his Visigoths to ravage Illyrium, Macedonia, and Thrace before he finally arrived with his army in southern Greece. [5] The Visigoths returned to their temporary base in Epirus after losing a battle to Stilicho’s forces, but the army was largely still intact. [6] Many modern scholars believe that Alaric’s entire campaign was manipulated by Stilicho – the general purposely allowed the Visigoths to plunder the region so that he could be the savior and gain control at the expense of the East. [7] But Alaric I was not content with mere plunder, he desired to have a territory for his people within Roman territory so he decided to bring his request straight to the emperor.

Since no one in either half of the Roman Empire appeared to be listening to Alaric, the Visigoth king decided to take his grievances straight to the emperor by invading Italy in 401. Alaric and his army ravaged towns in northern Italy until Stilicho arrived once more to save the day, forcing the Visigoths to accept his terms and leave Italy in 402. [8] Alaric did not plan to stay away until his dreams were realized, though, so he invaded Italy once more in 403, but was defeated again by Stilicho. After the defeat in 403, Alaric led the Visigoths back through the Balkans where they encamped in Epirus for nearly five years. [9]

Honorius probably thought he heard the last of Alaric in 403, but Stilicho no doubt knew better. The seeming stability that Rome enjoyed on Italy’s northern border in the first years of the fifth century ended when the Rhine River was breached in 406 by a horde of Germanic tribes, foremost of them were the Vandals. Honorius was forced to send Stilicho and his best troops to Gaul to fight the new menace, which left Italy’s northern frontier wide open for an ambitious warrior king such as Alaric I. [10]

In 408, Alaric I led his Visigoth army out of Epirus to Noricum on Italy’s northern border, where they camped and sent an embassy to Rome. Alaric I demanded 4,000 pounds of gold in return for fighting against a usurper who challenged Honorius in Gaul. The young emperor was not happy about the situation, but he was pressured to accept the demands by Stilicho, who understood the extent of the Visigoth’s military capabilities. [11] The payment had the effect of temporarily mollifying Alaric’s demands for Roman land, but it also led to the formation of a palace conspiracy. A palace official named Olympius spread a rumor that Stilicho was plotting to usurp the Eastern throne on behalf of his son. The rumors were believed by many since Stilicho was a German and it seemed to many that the commander was doing little to stop the German Alaric. As proof, the conspirators pointed to the large gold payment that Alaric received, which was facilitated by Stilicho. The conspiracy gained strength until Stilicho was captured and beheaded on August 22, 408. [12]

Stilicho’s assassination was the worst imaginable thing that could have happened to Honorius. Stilicho was his most able commander and the only person in his army who appeared to have the ability to defeat Alaric. The Visigoth king clearly also had a high level of respect for Stilicho and was willing to listen to him. Stilicho’s assassination was followed up by an anti-German pogrom where Roman troops massacred the families of German auxiliaries. The events only hardened Alaric’s resolve and increased the size of his army when 30,000 German survivors joined him in Noricum. [13]

Despite the violent turn of events and the general lack of respect the Romans showed to him and his people, Alaric I continued to hope that he could come to some sort of permanent deal with Honorius. He promised to withdraw to Pannnonia if another sum was paid and hostages were exchanged, but the young emperor flatly refused. [14] Alaric was done negotiating.

After Alaric’s final offer was denied, he invaded Italy for a third time in the fall of 408. The Visigoths burned and pillaged numerous towns unopposed until they finally reached the walls of Rome. [15] Alaric I then ordered that all roads in and out of Rome be blockaded as well as river access to Ostia. Unfortunately for Alaric I and the Visigoths, though, Honorius was safely ensconced in the imperial residence in Ravenna, which meant that the king had to deal with the Senate. Alaric I soon found the Senate to be just as weak and feckless as the emperor and unable to grant him any of the major concessions he desired. When he realized that the Senators did not have the power to give his people land, Alaric I played on their desperate situation and demanded nearly all of the alienable property in the city from its starving citizens. The sixth century Byzantine historian, Zosimus, summarized the negotiations:

“He said that he would under no circumstances put an end to the siege unless he received all the gold which the city possessed and all the silver, plus all the movables he might find throughout the city as well as the barbarian slaves. When one of the envoys asked, “If you should take all these things, what would be left over for those who are inside the city?” he answered, “Their lives.” [16]

In terms of material goods, the siege was a major success for Alaric and the Visigoths. They took 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, and 4,000 silk tunics from the city, with many ancient statues being melted down to meet Alaric’s exorbitant demands. [17] Although Alaric I and the Visigoths claimed a major victory, they were far from done with Honorius and Rome.

The Sack of Rome

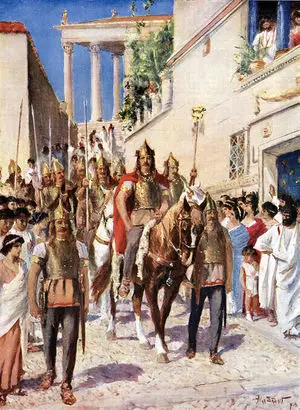

Although Alaric’s siege of Rome was financially successful, he was still unable to secure land within the Roman Empire for his people. He was not finished with Rome and by 409 his war had taken on a more personal note that was directed at Honorius. Alaric sieged Rome again in 409, forcing the Senate to accept his puppet, Priscus Attalus, as emperor. The move had the desired effect of pressuring Honorius to come to the negotiating table, but Alaric was attacked on the way to the negotiations. [18] Alaric deposed of Attalus, who was no longer of any use to him, and took his force to Rome once more, but this time the Visigoths would lay waste to the city. After camping outside of the city, the Visigoths gained entry on August 24, 410 through guile. According to the sixth century Byzantine historian Procopius, the Visigoths gained entry through a Germanic Trojan Horse.

“He chose out three hundred whom he knew to be of good birth and possessed of valour beyond their years, and told them secretly that he was about to make a present of them to certain of the patricians in Rome, pretending that they were slaves. And he instructed them that, as soon as they got inside the houses of those men, they should display much gentleness and moderation and serve them eagerly in whatever tasks should be laid upon them by their owners; and he further directed them that not long afterwards, on an appointed day at about midday, when all those who were to be their masters would most likely be already asleep after their meal, they should all come to the gate called Salarian and with a sudden rush kill the guards, who would have no previous knowledge of the plot, and open the gates as quickly as possible. . . But when the appointed day had come, Alaric armed his whole force for the attack and was holding them in readiness close by the Salarian Gate; for it happened that he had encamped there at the beginning of the siege. And all the youths at the time of the day agreed upon came to this gate, and, assailing the guards suddenly, put them to death; then they opened the gates and received Alaric and the army into the city at their leisure.” [19]

The Visigoths raped, robbed, and pillaged Rome and the Romans for two days but left all of the Christian churches intact. As a parting shot, Alaric I took the emperor’s sister as a hostage and left the vicinity. [20] Although Alaric I died shortly after the sack of Rome and his dream of a Visigoth homeland within Roman territory was never realized, his deeds were never forgotten.

Conclusion

Alaric I, king of the Visigoths, is a well-known historical personality because of his sack of Rome in AD 410. The event changed the course of history as it hastened the decline of the Roman Empire, but numerous factors contributed to make it a reality. The general weakness of the Roman Empire at the time and more specifically the weakness of Emperor Honorius were among the most important factors – in earlier periods, when Rome was strong, foreign armies could rarely get close to Rome, never mind sack the city. The death of the Roman general Stilicho should also not be overlooked. Stilicho was an able general and tactician who routinely defeated Alaric and the Visigoths on the battlefield. The general was also a diplomat and moderator who more than once brought the Visigoths and Romans to the negotiating table. After Stilicho died, there was no longer a voice of reason in the conflict. Finally, the abilities of Alaric I and his army played the pivotal role. Alaric knew when to use brute force and when to use guile and cunning, which allowed him to win numerous battles and to ultimately sack the greatest city of the ancient world.

Suggested Readings

- Bury, J. B. The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1967)

- Sennigen, William B., and Arthur E.R. Boak. The History of Rome to A.D. 565 6th Ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1977)

- Kyle Harper, The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire (Princeton University Press, 2017)

- John Boardman, edit. Jasper Griffen, Oswyn Murray, The Oxford History of the Roman World (Oxford University Press, 2001)

- Bryan Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome: and the End of Civilization (Oxford University Press, 2006)

References

- ↑ Bury, J. B. The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1967), p.24

- ↑ Bury, p. 64

- ↑ Rousseau, Philip. “Visigothic Migration and Settlement, 376-418: Some Excluded Hypotheses.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 41 (1992) p. 335

- ↑ Sennigen, William B., and Arthur E.R. Boak. The History of Rome to A.D. 565. Sixth Edition. (New York: Macmillan, 1977), p.451

- ↑ Bury, pgs. 66-67

- ↑ Burrell, Emma. “A Re-Examination of Why Stilicho Abandoned His Pursuit of Alaric in 397.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 53 (2004) p. 252

- ↑ Bury, p. 79

- ↑ Bury, p. 77

- ↑ Bury, p. 78

- ↑ Bury, p. 81

- ↑ Bury, p. 84

- ↑ Matthews, J. F. “Olympiodorus of Thebes and the History of the West (A.D. 407-425).” Journal of Roman Studies 60 (2004) p. 83

- ↑ Bury, p. 91

- ↑ Bury, p. 91

- ↑ Bury, p. 92

- ↑ Zosimus. Historia Nova: The Decline of Rome. Translated by James J. Buchanan and Harold T. Davis. (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 1967), Book V, 40

- ↑ Bury, p. 94

- ↑ Bury, p. 96

- ↑ Procopius of Caesarea. History of the Wars. Translated by H.B. Dewing. (London: William Heinemann, 1916), Book III, ii, 14-24

- ↑ Bury, pgs. 96-97