Interview:Voodoo, Kidnapping and Race in New Orleans during Reconstruction: Interview with Michael A. Ross

In October, the Oxford University Press will be publishing The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case: Race, Law, and Justice in the Reconstruction Era by Michael A. Ross, an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland. Ross's first book, Justice of Shattered Dreams: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court during the Civil War Era, examined Justice Miller's career on the Supreme Court. Ross has changed pace and his next book follows the 1870 kidnapping of a white seventeen month old girl, Mollie Digby, by two African American women in New Orleans. While virtually unknown today, the case was a national sensation at the time. Everyday, newspapers around the country were publishing reports of the kidnapping and subsequent trial. Unsurprisingly, the story became intertwined with the racial politics of Reconstruction. Here's my interview with Michael Ross about his new book.

Your previous book, Justice of Shattered Dreams: Samuel Freeman Miller and the Supreme Court During the Civil War Era, focused on the impact of Justice Samuel Freeman Miller on the Supreme Court. How did you shift from looking at the Supreme Court to examining Reconstruction in New Orleans?

For my first book, I did a lot of research on New Orleans during Reconstruction because Justice Miller authored the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in a case, the famous Slaughter-House Cases, that emerged from the fearsome political and legal struggles that took place in New Orleans during that era. I stumbled across the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case while doing that research. Every historian has had a moment like this. You are immersed in old letters or newspapers when a different story from the one you are working on catches your eye. In the documents you find an account of something no one has written about before, an untold story begging to be told. Usually when this happens, you pause, shake your head, think “wow, that would be great to tackle someday,” and then return to the task at hand. Seldom do you go back to it. The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case is an example, for better or worse, of what happens when you actually take the bait and decide that the event you stumbled across is too rich, too full of historical implications, to pass up.

When I first found the Digby case, I was reading all of the 1870 New Orleans newspapers, looking for references to the Slaughter-House Cases and the efforts by ex-Confederates to obstruct Reconstruction in the state and local courts. When I reached the June 1870 editions, the story of an alleged Voodoo abduction demanded a quick read. ‘That can’t possibly have happened,’ I thought to myself. The press had to have been spreading unfounded rumors. The New Orleans papers, after all, also reported ghost sightings. But to my amazement, each day’s paper contained new articles about the Digby kidnapping—including reports of the police arresting and interrogating Voodoo practitioners. And by the time it was clear that the human sacrifice rumors were exaggerations, the story had taken other compelling turns. (Editor's note: Ross has more about the human sacrifice allegations at his Tumblr blog - michaelaross.tumblr.com.)

I was hooked, and just like the readers in 1870, I looked to each day’s newspapers for the latest revelations in the Digby investigation. I also checked to see if anyone had ever written about the case before. I had never heard of the Digby case, but surely someone had already authored an article or book about it. I was surprised to find the story was almost untouched by historians despite the fact that the case made headlines across the country in 1870.

So what was it about the case that you found so compelling?

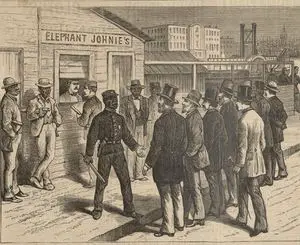

One of the things that I found so compelling about the case was how quickly it became intertwined with the momentous events of Reconstruction. New Orleans was a city on edge in June 1870 when the papers reported that two African American women abducted 17-month-old Mollie Digby from in front of her family’s home in the working-class “back of town.” It was the height of Radical Reconstruction. African American men could now vote, serve on juries, and hold public office, and black men and women now demanded service in formerly whites-only restaurants and saloons. Reconstruction Governor Henry Clay Warmoth had also just integrated the New Orleans police force and black officers now patrolled the streets. Many white residents, still emotionally wounded by Confederate defeat, seethed as the new order emerged.

After the Voodoo abduction rumors began, the white press seized on the Digby case as an example of a world turned dangerously upside down, and they predicted that the integrated police force would let the crime go unsolved and unpunished. Governor Warmoth responded by getting personally involved the case, offering a state reward of $1,000 for recovery of the child or the arrest and conviction of the abductors, and he ordered New Orleans’s chief of police to put his best African American detectives in charge of the investigation. If black detectives could solve a high-profile, racially explosive case, it could build public confidence in all of the new African American public servants.

In the Digby case, lead Detective John Baptiste Jourdain became the first African American detective ever to make national news. Right there I knew I had a story worth telling, but there was even more to come. When private citizens supplemented Warmoth’s reward and the promised amounts reached $5,000, the case became the “Powerball” of 1870. Everyone who saw an African American woman walking with a white baby wondered if the child was Mollie Digby. Leads poured in from across the South and the detectives even consulted clairvoyants. Eventually, the police arrested and put on trial two strikingly beautiful and stylish Afro-Creole women and a sensational, headline grabbing trial followed.

Did Reconstruction in New Orleans differ from Reconstruction in the rest of the South? Was there anything unique about the New Orleans experience?

I have always argued that if there was any hope Reconstruction could have succeeded, the best chance was in New Orleans where Governor Warmoth hoped to build a coalition with Whiggish businessmen that could broaden the base of the Republican party so that it might survive the eventual removal of federal troops. Unlike many areas of the South, antebellum New Orleans had been a Unionist stronghold, and in the election of 1860, New Orleans voters overwhelmingly supported Unionists John Bell and Stephen Douglas. Businessmen had correctly feared that a civil war would bring economic catastrophe. The city’s population also included thousands of transplanted northerners who ran the public schools, Protestant churches, several newspapers, and significant portions of the commercial community. These same men, Warmoth hoped, might now accept biracial Republican rule if he could follow through on his promises to professionalize the police force, to rebuild the levees, clean the streets, move the disease-ridden slaughterhouses away from the city’s water supply, and to complete railroads linking New Orleans to Houston, Illinois, and the Northeast.

New Orleans’s population also included the Afro-Creoles, former free persons of color who had flourished in the city before the Civil War under Spanish, French, and even American rule. Many Afro-Creoles—a class that included doctors, lawyers, newspaper editors, poets, and merchants—had long sent their children to the best schools in the North and Paris, and their sophistication allowed Warmoth and the Republicans to counter reactionary whites’ favorite argument—that African Americans, recently freed from slavery, were allegedly too ignorant to serve as jurors, policemen, and government officials. Although many New Orleans whites viewed all black people with disdain, some accepted the Creoles as commercial partners, a reality that fueled Republicans' hopes for an urban coalition between erudite black leaders and white businessmen who cared more about economic development than racial dogma. The lead detective in the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case, John Baptiste Jourdain, was an Afro-Creole.

What does this case teach us about Reconstruction?

I think The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case is a story filled with small moments that had larger implications. I don’t want to give away too much, as the book is, in part, a “whodunit.” But I can say that I tried to tell the story from the perspective of those who lived it. It is important to remember that in 1870 no one knew whether Reconstruction was going to succeed or fail. One reason reactionaries fought so violently against the biracial Republican governments was their fear that Reconstruction might actually work.

Too often, I think, we read history backwards from the Plessy v. Ferguson case. We simply assume that Reconstruction was doomed and that the South’s descent into Jim Crow was inevitable. The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case depicts 1870 as one of those rare moments in American History where real change was possible. One place this can be seen is in the trial of the accused women. The evidence against the defendants was mixed. Some facts suggested guilt, others innocence. Had the Digby case occurred in the early twentieth century South, the result would have been foreordained. Black defendants charged with committing sensational crimes against whites had little hope for acquittal.

Yet in 1870 in New Orleans no one could be sure of the outcome. Because 1870 was the height of Radical Reconstruction, the state government that prosecuted the defendants was not dominated by white supremacists bent on keeping African Americans in line. Blacks and whites served together on the jury. While at the same time, much of the evidence against the accused was the result of the work of African American detectives who now testified against members of their own race. Unlike the trials of the Jim Crow era, the outcome was in doubt even as the jury’s foreman stood in a jammed courtroom to announce the verdict.

How would you recommend using this book in a class? How can your book help students better understand the issues surrounding Reconstruction?

I am always looking for books to assign in class that tell a story that is compelling enough to pull student readers in, but that also illuminate the main themes of my course. I often assign books like Kevin Boyle’s Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age and Jill Lepore’s New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan that use a single trial or event to reveal a larger world. I hope The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case will be assigned (and read) for the same reasons.